Heating Options for a Small Home

A conventional furnace is overkill in a small, well-insulated house. Here are some better options.

Synopsis: Houses being built today are much better insulated (and often smaller) than the ones built even a few years ago. Nowadays, a well-insulated, 1200-sq.-ft. house may have a design heat load of only 10,000 to 15,000 Btu/hour, rendering even the smallest available boiler or furnace (50,000 to 80,000 Btu/hour) overkill. In this article, contributing editor Martin Holladay looks at more appropriate solutions: a single point source such as a woodstove, a pellet stove, or a direct-vent gas space heater; electric-resistance baseboard heaters; a packaged terminal heat pump (PTHP); a ductless minisplit heat pump; and a hot-water coil in a ventilation duct. The article includes two examples of homes that use one or more of these solutions: a superinsulated duplex with a design heat load of 12,000 Btu/hour, and a net-zero-energy house with a design heat load of 10,500 Btu/hour.

Most U.S. homes are heated with either a boiler (which distributes heat by circulating hot water through tubing) or a furnace (which distributes heat by circulating hot air through ducts). Because new homes often include central air conditioning, which requires ducts, furnaces have become far more common than boilers. But houses being built today are much better insulated (and often smaller) than the ones built even a few years ago. Nowadays, a well-insulated, 1200-sq.-ft. house may have a design heat load of only 10,000 to 15,000 Btu/hour, rendering even the smallest available boiler or furnace (50,000 to 80,000 Btu/hour) overkill. Fortunately, there are other options.

Heating with a single point source

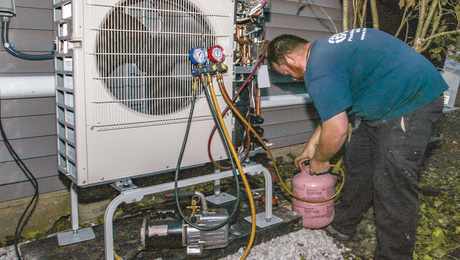

One way to lower the cost of your heating system is to heat your house from a single point source rather than using pipes or ducts to distribute heat from an appliance in a mechanical room or basement. This can be done with a woodstove, a pellet stove (see “Is Wood Heat the Answer?”), or a direct-vent space heater.

These solutions work best in compact homes with open floor plans. Of course, the tighter the home’s thermal envelope and the thicker the insulation, the more likely indoor temperatures will remain fairly consistent from room to room.

If bedroom doors are kept open during the day, temperatures throughout a small house should be fairly uniform. When doors are closed at night, bedroom temperatures sometimes drift lower; in midwinter, bedroom temperatures may be about 10°F colder than common areas by morning. While such fluctuations are perfectly acceptable to some homeowners, others may balk at the idea of a cool bedroom.

Expensive equipment is overkill

It’s worth mentioning two heating options—in-floor radiant systems and ground-source heat pumps—that rarely make sense for small homes.

Although in-floor radiant systems are a good way to heat a poorly insulated house, they are overkill and a waste of money in a small, tight house. If your goal is simplicity, there’s no reason to invest $12,000 or more on a boiler, one or more circulators, and hundreds of feet of tubing just to supply 15,000 Btu/hour on the coldest day of the year.

If you need only a small amount of space heat, it’s equally unwise to invest in a ground-source heat-pump system, which usually costs at least $18,000.

The money required for in-floor radiant piping or a ground-source heat pump would be better invested in improvements to the building envelope—for example, improved air-sealing, more insulation, or high-quality triple-glazed windows. Builders achieving the Passive House standard have demonstrated the many advantages of superinsulation; if your building envelope falls short of Passive House performance levels—and it probably does—then envelope improvements usually make more sense than an investment in expensive heating equipment.

No matter what type of heating equipment you choose, the first step should always be a thorough, accurate calculation of your home’s design heat load. Even contractors who do perform a Manual J calculation—a method published by the Air Conditioning Contractors of America (ACCA)—rarely bother to input all the necessary information without fudging and adding unnecessary “safety factors.” To avoid the typical result—oversize heating equipment—an accurate heat-loss calculation is essential.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: