A while back, my company built a set of freestanding curved stairs for a client. It was such a successful project that I decided to repeat it in my own house. I figured the sweeping curve and implied lightness of the new stairs would look better in our two-story atrium than the existing set of traditional stairs with a midlevel landing. The central trick to the helical stringers is building two curved, temporary stud walls that serve as a lamination form. The wall layout also is used to determine the rise, the run, and the taper of the treads.

To plan the layout, I drew out everything on the floor first. Next, I made a 3-1/2-in.-wide paper template of the inside and outside radius, then transferred the template lines onto 3/4-in. plywood and cut out the curve to make the top and bottom plates.

Working with my wife, Pam, I built the walls on the curved plates by lining up each stud with a riser mark. Starting at the bottom, we marked the rise on the first stud; for each successive stud, we added one tread height. This gave us the baseline for the top of the stringer, which we then raised 2 in. to accommodate a 1-in.-wide nosing.

For the stringers, we ripped 3/8-in. plywood into pieces 15-7/8-in. wide. After making the plumb and level cuts, we bent the first layer onto the stud walls following our stringer line and attached it using 1-1/4-in. drywall screws. I used a brush to coat the entire surface of the next layer with yellow glue, then screwed that layer over the first layer, offsetting the seams by 4 ft. We built up 11 layers, creating a 4-1/8-in.-thick stringer.

Once the glue was dry, we removed the stud walls. Then we removed the stringers, covered them with oak veneer, and replaced them. I had 1/4-in.-thick steel angle brackets welded to the steel header above to secure the stringers at the top, and then I bolted the bottom of the stringers to the floor. Using rough-sawn 2-in. white oak salvaged from an old barn, I made the treads and attached them to the stringers with steel stair-tread brackets from Simpson Strong-Tie.

For the handrails, I cut 1/4-in. by 1-1/2-in. oak strips and, using the stringer top as a form, laminated 15 layers with clamps and glue. After the glue dried, I sanded them down and routed a handrail profile onto the edges. Posts installed at the top and bottom of each stringer were made from 4×4 stock from the old barn.

I attached blocks to the bottom of a router for a guide and plowed a 1/2-in.-wide by 3/4-in.-deep dado in the bottom of each handrail to accept the 1/2-in.-sq. steel spindles. On the top of the stringers, I drilled 5/8-in. holes on 4-in. centers. We used 1/2-in.-sq. steel bases at the bottom of each spindle to cover the round holes. At the top and bottom of every tenth spindle, I put a small screw to attach the spindle solidly to the stringer and handrail.

First, draw the layout on the floor

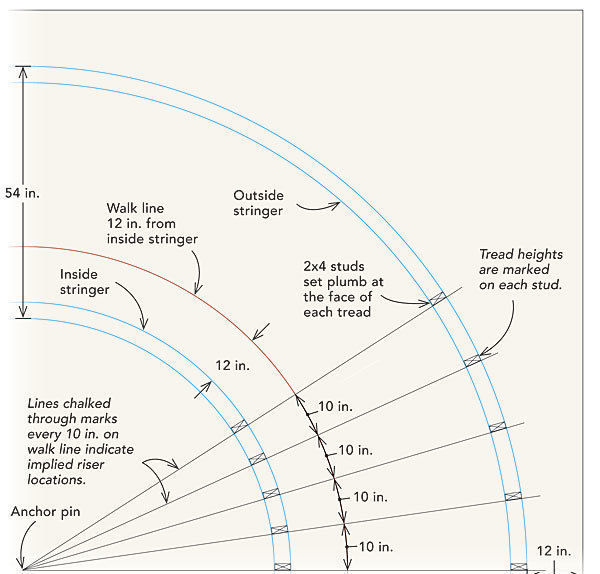

To compute the stair’s rise and run on a radius, the author established his starting point on the floor directly below the upper landing. With a string hooked to an anchor pin in the floor, he drew the line for the inner stringer, then drew the walk line and outer stringer. Through trial and error, he measured the tread width at the walk line and found that a width of 10 in. would create the run he wanted. To determine the rise, he divided the total rise by the number of treads that would produce an approximate rise of 7 in. After the layout was established, he transferred the stringer radii onto plywood, which he then cut and used for plates. Studs positioned at the face of each tread created a form that he used to laminate the stringers.

Temporary wall functions as form

Templated from the layout drawn on the floor, the plywood wall plates are used to build a pair of curved walls that replicate the curve of the stairs. Temporary bracing keeps the walls plumb. Each stud is positioned at the implied location of a riser, and each tread height is marked on that stud. The stringers are laid up along these marks. Each successive layer of 3/8-in. plywood is screwed and glued to the previous layer. Clamps help to maintain a consistent lamination.

Make sure they work

When the glue has dried on all the laminations, remove the stud walls, snap off protruding screws, and patch and sand the stringer surface in preparation for veneer. Fasten the stringers to the upper landing with steel angle brackets welded and bolted to the steel header.

Beautification, skin deep.

Apply the veneer with contact cement to all faces of the stringers once they have been unbolted from their positions. Flush-trim each face before gluing the adjoining face.

Photos by Pam Hawkins; Illustration by Rodney Diaz

View Comments

I have been searching for a while, learning about laminated stingers. I have read several articles, and watched a plethora of videos.. This article is one to pin. Simple, and full of great info. It cuts all the fluff and gets straight to the business. Thank you for writing it.