Cabinet Door Shoot-Out

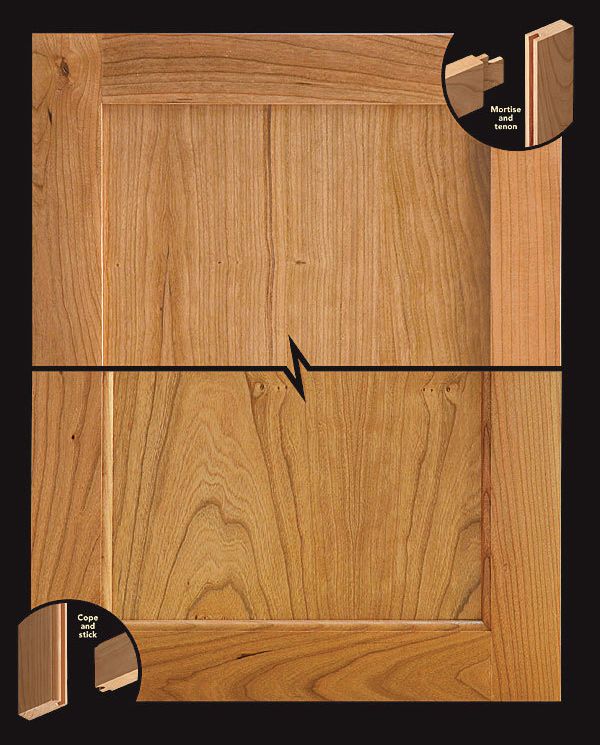

Mortise-and-tenon vs. cope-and-stick joinery: Experienced cabinetmakers share their preference.

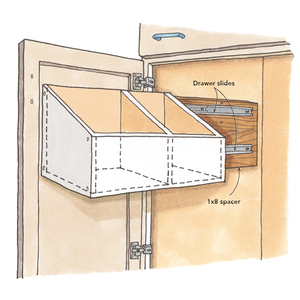

Synopsis: For this article, Fine Homebuilding brought two cabinetmakers together to see how they would approach the construction of a simple cabinet door made of cherry with a 1/2-in. cherry-plywood panel. Contributing writer Scott Gibson made his cabinet doors with mortise-and-tenon joints, and Joseph Lanza made his with cope-and-stick joints. Each cabinetmaker describes his method—including set up, cutting, and assembling—and close-up photos illustrate each step. Gibson used a tablesaw and a mortising machine as well as some basic hand tools. He admits that his method is more time-consuming than cope-and-stick joinery, but says that once the machine settings are dialed in, the work goes surprisingly fast. Lanza made all of his cuts with a table-mounted router and cope-and-stick bits. He likes the speed with which he can make such a door, and although he believes cope-and-stick joints are strong enough for most cabinet doors, for larger doors he would consider using slip tenons or dowels for reinforcement, or possibly mortises and tenons.

MORTISE AND TENON

I have a lot of confidence in a traditional mortise-and-tenon door. The wood-to-wood contact is substantial, meaning there’s a large glue area, and the joints are highly resistant to racking. A door with tight-fitting joints is extremely durable.

The process is more time-consuming than making cope-and-stick joints with a router, and it isn’t as well suited to making doors on a job site. That said, the work goes surprisingly fast once the machine settings have been dialed in. For tooling, I use a tablesaw and a mortising machine in addition to a few basic hand tools. Mortises could be cut with a drill press or even a portable drill plus a chisel, but the mortising machine is faster and more accurate.

It may be overkill to make doors the way I do, but it wouldn’t be the first time I overbuilt something. The advantage I see is that with one setup, mortise-and-tenon joinery can be used to make all the frame-and-panel parts, face frames, and doors for a kitchen’s worth of cabinets. It takes some fiddling to get the setup, but once that’s done, many pieces can be run off quickly.

COPE AND STICK

I don’t know if it qualifies yet as traditional, but millwork factories were producing cope-and-stick joinery a hundred years ago. If you have a table-mounted router, cope-and-stick bits offer a quick, accurate way to make cabinet doors without a big investment.

With a glued-in plywood panel, cope-and-stick doors are extremely strong. Solid-panel doors can be made stronger by adding interior rails or stiles, but for larger doors, cope and stick may not be the best choice, unless the joints are reinforced with slip tenons or dowels. The extra work required might tip me in favor of using mortises and tenons for larger doors.

Although maybe not the best choice for period reproductions, cope-and-stick doors are a good option for jobs that don’t require the structural or emotional benefits of mortise-and-tenon joinery. Most of the modern solid-wood cabinet doors in this country are made with a simple cope-and-stick joint, and the vast majority are holding up just fine.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: