Most Americans are attuned to the connection between the energy efficiency of their homes and the money it costs to operate them, and a few are inclined to spend at least some of their budget on energy efficiency improvements, according to Energy Pulse ’11, the seventh annual market study conducted by energy-focused advertising and consulting firm Shelton Group.

The problem is, if consumers make any improvements at all, many take some but not all of the steps they need to significantly decrease in their energy bills.

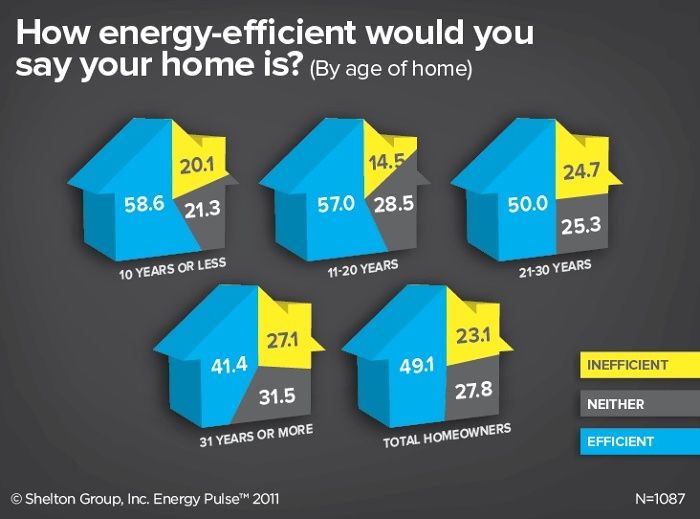

Compared to Energy Pulse results compiled in 2010, the 2011 study shows that more people – 23% vs. 14% in 2010 – rate their homes as inefficient, although the percentage (71%) who said they were using the same amount of energy as they did five years ago remained about the same.

Some of the study’s more interesting – and, in some ways, puzzling – findings are pegged to consumers’ responses to utility bill increases, their perceptions of the reasons for the increases, and their opinions about what policy responses are needed to address rising energy costs.

When good enough really isn’t

In 2009 and 2010, for example, consumers told Shelton Group that their bills would have to increase by $128 before they would make energy efficiency improvements. For respondents in 2011, that threshold had dropped to $112, and yet they had embarked on fewer energy conservation behaviors and major energy retrofit improvements in 2011 – an average of 2.6 – compared to 2010. The study notes that four such improvements – the “magic number” of upgrades, according to the study – tend to produce meaningful energy savings, while anything short of that tends to yield mediocre results.

Not that the 2.6 improvement level is necessarily an inexpensive commitment: homeowners cited window replacement and adding insulation as the top two improvements they had undertaken.

But the study, which analyzes responses from 1,502 people via online and telephone inquiries collected August 9–22, also indicates that Americans are increasingly likely to blame oil companies (rather than themselves) for high energy prices, and that they now rank as top priorities domestic oil and natural gas production over development of alternative energy sources. What’s more, alternative energy sources, fuel efficient cars, and energy efficient homes were more likely to be cited as top priorities in 2010 than in 2011 by margins of 37.6% in 2010 to 28.3% in 2011, 24.6% to 17.9%, and 21.7% to 13.1%, respectively.

The bottom line is that most Americans are still not knowledgeable about alternative energy sources, in spite of the millions of dollars spent by government programs to promote them. Many people, the study notes, don’t know what the most common fuel source is for electrical power (coal) or what steps to take to cost-effectively retrofit their homes. Their homes might be a bit leaky, but the attitude seems to be that they’re energy efficient enough.

The marketer’s angle

For Shelton Group’s purposes, of course, it is important to try to understand what motivates – or what might motivate – consumers to pay attention to energy efficiency deficiencies and possible solutions. In its executive summary of the Energy Pulse study, the company points out that energy use and energy waste are, until the utility bill arrives, invisible features of a home’s operation. So Shelton Group is trying to come up with ways to make energy seem like less of an abstraction and more like a tangible asset in which consumers will have a stronger personal interest?

Certainly a tripling of energy prices would generate more intense interest in energy and ways to reduce its use. But the study also suggests tying messages that encourage energy efficiency to consumers’ core values.

With that in mind, the analysis cites possible approaches to four kinds of consumers:

For absolutists, the energy message should be “about doing the right thing, which will give them a sense of righteousness and relief.” For individualists, “we should appeal to their need for status and financial gain, which will give them a sense of security and achievement.” For humanistic thinkers, “we should connect energy efficiency to being part of a movement or a community, which will fulfill their need for personal connection.” Finally, for systemic thinkers, the emphasis should be on “themes of innovation, possibility and problem solving should resonate and spark feelings of integrity and competence.”

The trick, the study points out, will be to come up with ways to effectively communicate key concepts to those four types of consumer. The authors of analysis suggest that the federal government, whose energy policy has not been sharply focused, could be an ideal resource, but its message must be coherent and consistent:

“Our studies have shown for years that Americans expect government and companies to fix some of the pressing issues of the day—including energy—and they’re looking for leadership. How can we expect them to have a personal energy plan if there’s no example for them to follow?”

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Americans are increasingly inclined to think of their homes as energy inefficient, according to the Shelton Group’s Energy Pulse ’11 study. Compared to survey results for 2010, the percentage of consumers rating their homes inefficient in 2011 increased significantly, from 14% to 23%, although the percentage who thought they were using the same or less energy than five years ago remained unchanged at 71%.

View Comments

An interesting related article is at Green Building Advisor, where an architect writes that the cost of PV installed on a house has dropped 45% in the past year to around $4500 per kW or from $8 per watt to $4.50 per watt: http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/guest-blogs/pv-systems-have-gotten-dirt-cheap

Builders and remodelers need to be able to help consumers make smart choices, though, on where to spend their energy upgrade dollars. If your advice results in lower bills and a more comfortable house, you will get a lot of referrals. If the bills don't go down, you may gain yourself a bad reputation. To learn about prioritizing energy upgrades, turn to the Energy Nerd: http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/musings/energy-efficiency-pyramid

Perhaps the most important part of this article, however, is the last part that talks about types of consumers. If you don't connect and make the sale, you never get the chance to show how good you are.

An interesting article, I'd guess you'd call it the 'Psychology of perceived energy usage by Americans". Most of the homes in New England were built when oil was like, 20 cents a gallon, so few of the walls of these homes have any insulation at all and windows are single-pane. If you had asked back then if homes were 'energy efficient', most would have indicated yes, which really meant "It's cheap to heat my house".

Times and perceptions have changed, with oil hovering around $4 a gallon. But today, even in Massachusetts, where there are financial incentives for getting insulation blown into residential walls, few people take advantage of such an insulation retrofit because of the effort involved.

In the end, it's all a question of money: how expensive must oil become before residents are definitely convinced their homes are energy inefficient and become motivated enough to do something about it? $6 a gallon, $8 a gallon?