Torture Test: Spade Bits and Beyond

We take traditional spades and their modern competitors for a spin.

Synopsis: Spade bits provide a low-cost means for plumbers, electricians, and framers to drill medium- to large-diameter holes. In addition to the original paddle-shaped spade, bits are now available with barbed edges, curved paddles, and self-feed screw tips. For this article, electrician Brian Walo put 13 spade bits (1 in. dia. and 6 in. long) through two tests: a high-speed/low-torque test and a low-speed/high-torque test. The Bosch Daredevil, a curved-paddle bit with a self-feed screw tip, not only was the best overall performer, but it also yielded the lowest cost per hole. As a group, the fluted bits performed poorly in the high-speed/low-torque test, but they outdistanced all other competitors in the low-speed/high-torque test. A third test was also performed, on wood spiked with framing nails, but because few bits survived this test, results are not included in the article.

Familiar job-site companions, spade bits have long filled the void for plumbers, electricians, and framers needing to drill medium to large-diameter holes without lugging around a dedicated 1⁄2-in. right angle drill. Spade bits are relatively inexpensive and widely available in a range of sizes to suit most tasks on the job, making them an easy choice for tool buyers with slim budgets.

Because they are such a common sight on the job, we began to wonder how the brands would stack up against each other for speed and durability in a couple of different scenarios. Also, in case you missed it, the market has expanded beyond the standard paddle shaped spade and now includes bits with barbed edges, curved paddles, and self-feed screw tips.

Our goal? To see if the new spins on the traditional spade design affect performance and longevity, or whether the traditional spades would prove the old adage about not fixing something that’s not broken.

Styles in spades

Spade bits come mostly in two variations: flat and barbed. The flat-blade bits vary slightly in their design. Some incorporate curved paddles in an effort to clear wood chips, but most are essentially cutting blades with straight, sharp edges. In a now-common offshoot of flat-blade bits, many spades have barbs on each side of the paddle to score the surface of the cutting material and, presumably, to feed material to the cutting edges. A third component, not often seen on traditional spade bits, is the self-feeding screw tip, which accelerates the cutting speed by pulling the bit through the material.

These days, spade bits also seem to be sharing shelf space with some relative newcomers to the field. Self-feeding fluted bits appear to be gaining traction in the wood-boring-bit market and are often touted as being faster and more durable than standard spade bits. Their distinctive spiral shape is a substantial departure from the traditional spade, but they aren’t quite auger bits, either. Although sold at a premium price, these bits are often marketed as direct competitors to spades, so we thought it fair to include them in our test.

How we tested

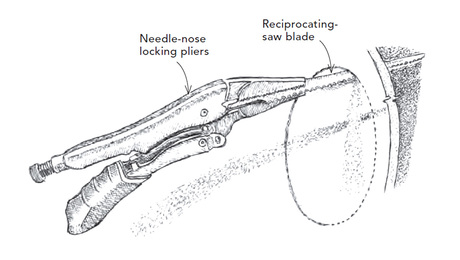

To find out just how well each bit stacks up to its peers, we built a dedicated drilling rig. A sled with vibration-minimizing supports was securely mounted to a pair of drawer slides. The sled held the drill and was attached via a small pulley and cable to a weighted bucket hanging below the rig to pull each bit through the material with the same amount of simulated hand pressure.

To give each brand a fair shake, the rig was built to accommodate both a high-rpm (2500 max), low-torque 6-amp drill that you might find in thousands of household-tool collections (DeWalt 3⁄8 in.; D21008), as well as a low-rpm (500 max), high-torque 9-amp drill more commonly found on construction sites (Ridgid 1⁄2 in.; R7121).

Each bit was timed on its first hole, then tested repeatedly until the time to complete a hole doubled, determining its point of failure.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: