Nestled into the western slope of Jobber’s Mountain in northern Virginia sits the Hazel River Cabin, a home designed by Washington D.C. architect David Haresign. When David submitted his project for consideration in our annual HOUSES issue, I knew right away that we had come across a home that was unlike any other. Staffers Brian Pontolilo and Maureen Friedman had similar reactions when they saw the project, which is a careful assembly of historic cabins that have been reinterpreted into a modern home.

In fact, the project was so unique that it didn’t seem quite right to publish it in a regular article. Instead, we chose to feature it on the back cover of our March issue as Maureen Friedman’s piece “Linking logs.” I spoke with David last week to get some better insights into his design process. Here, in his own words, he takes us through the Hazel River Cabin.

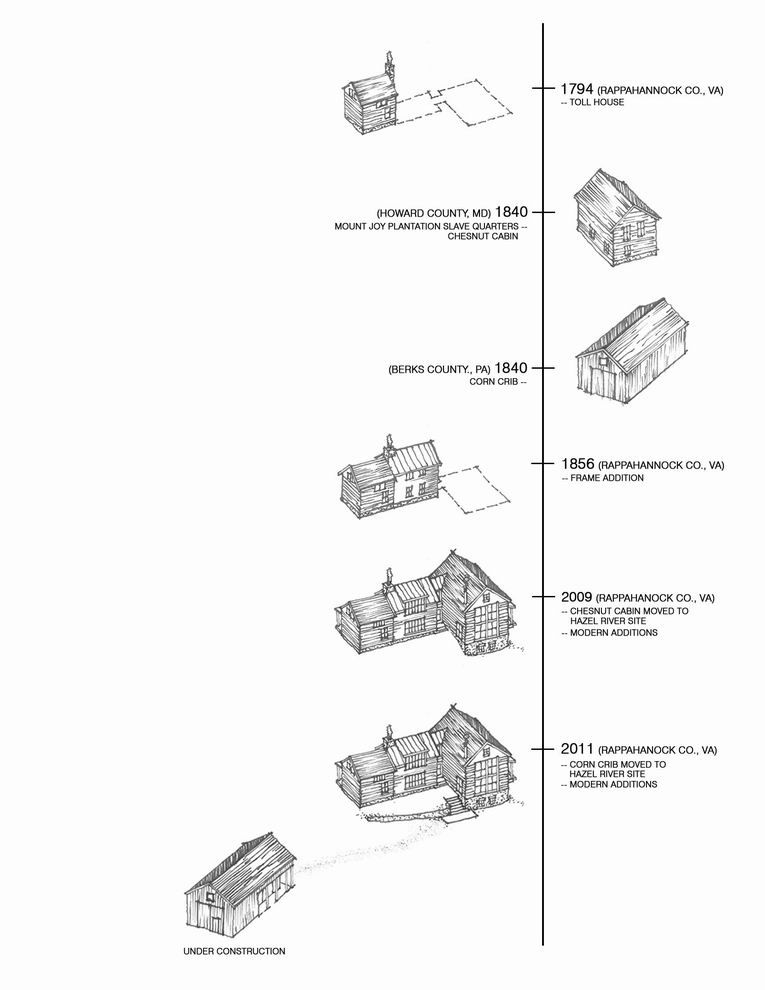

Not everyone is in the position to combine a 218-year-old toll keeper’s cabin with a 156-year-old addition and a 172-year-old chestnut cabin to make a new home. However, David’s approach highlights design lessons that are valuable to anyone redesigning an older home to accommodate a contemporary way of living, while striving to acknowledge and respect its original character.

The Program

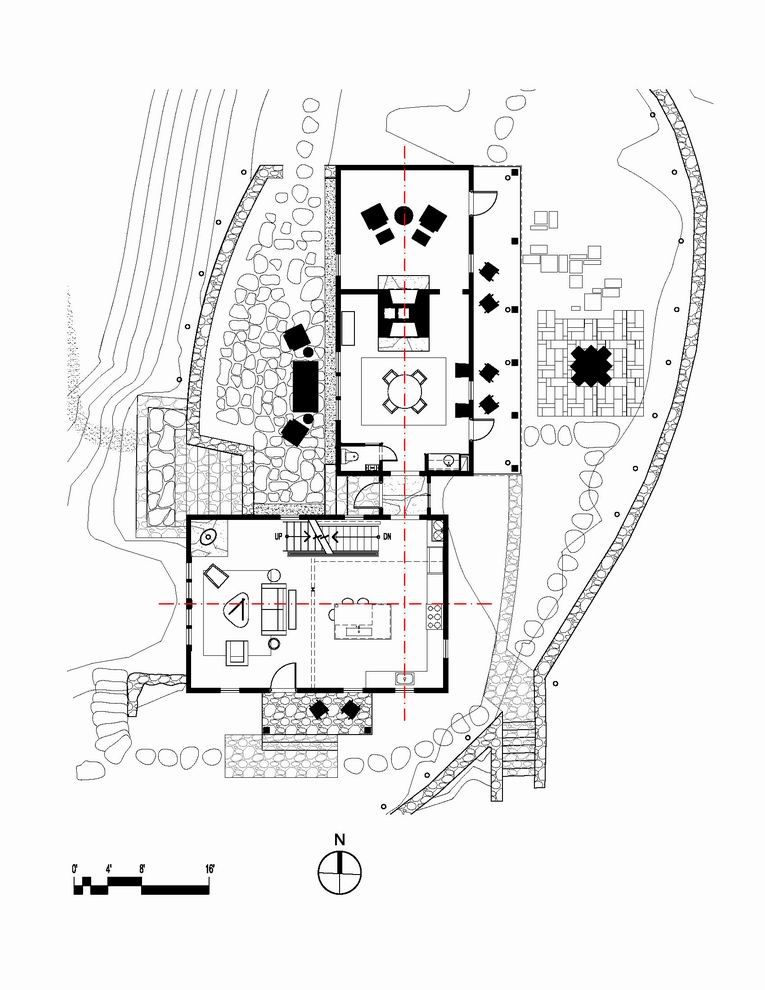

The client, Joe, initially thought that he had a teardown of two poorly framed buildings. After beginning demolition on the structure, Joe discovered the 1794 toll keeper’s log cabin beneath a layer of wood clapboards. He did some research and learned about the history of the site, the cabin, and the 1856 framed addition. Instead of proceeding with the teardown, Joe hired a local log-cabin-restoration contractor. After Joe and the contractor were in the initial phases of work, and Joe had a better sense of what he had, Joe felt that the lone cabin was too small and cramped with its 7-ft.-6-in.-tall ceilings. The cabin-restoration contractor told Joe about an additional derelict chestnut cabin from 1840, the former slave quarters from Mount Lovejoy Plantation in Howard County, Md., that he could procure and bring to the site. Soon after, he called me.

Joe wanted to use the new home as a retreat. He wanted the design to create a memorable renovation that respects the existing character of the cabins; celebrates the beauty of the logs, wood framing, and stone fireplaces; and incorporates all of the conveniences of a modern home. The space program was simple. The home would need:

- A large modern kitchen that could open into the main living area and a dining room that could comfortably accommodate six to eight people.

- A library, which could double as an additional sleeping area.

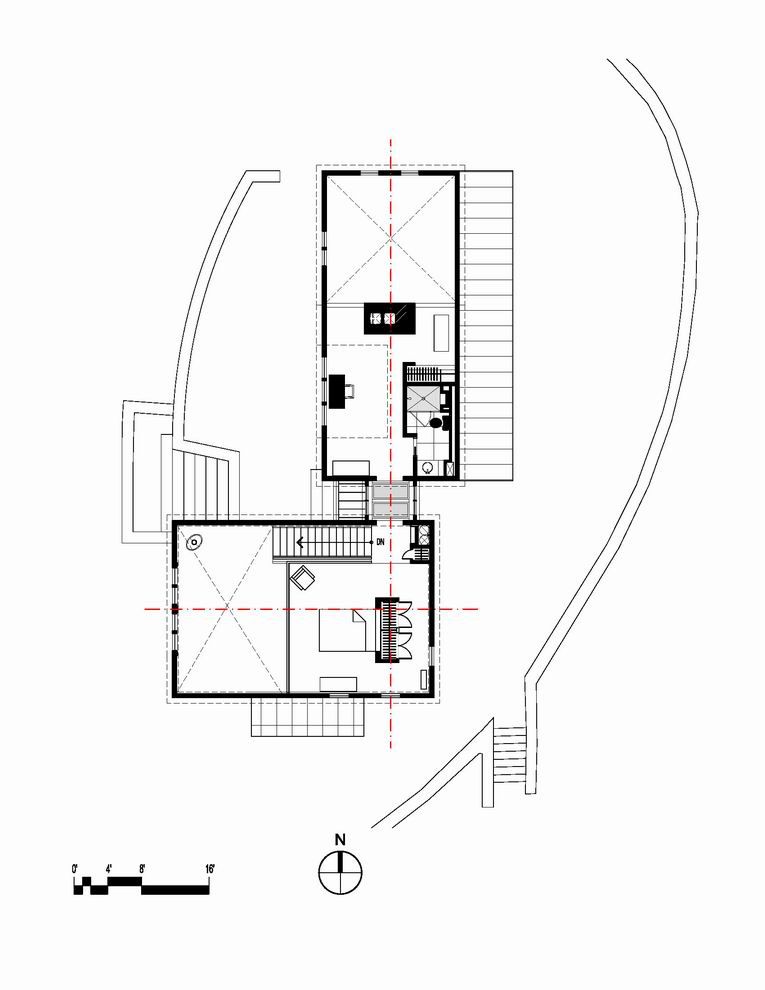

- Two bedrooms, each with a private bath.

- A study/sitting area adjacent to the main sleeping area.

- An equipment room for HVAC, boiler, water heater, water treatment, electrical panels with automatic transfer switch [generator], lighting controls, and audio equipment.

The property is in an agricultural trust, and Joe requested that the home’s total area be less than 2,500 sq. ft.

Contextual Modernism

Some may have looked at these cabins and set out to restore them instead of transforming them into something new and different. However, we use spaces very differently than when these cabins were originally constructed, so a traditional restoration simply would not have worked. For restorations, renovations, additions, and adaptive-use projects, I have always applied a simple design principle that I call “contextual modernism.” I aim to add new elements, like modern technology and precisely manufactured components, that respect and celebrate the character of the original structure yet remain clearly contemporary. For example, in this home, the modern elements are not hidden or blended into the old structure in any way. The modern additions, like the steel support beams, stand in stark contrast to the original structure. Steel is a more modern material – clearly from a different period than the log structure – but it also expresses an essential, rough-hewn character that lets the two materials work remarkably well together. This approach to material and finish selection is a result of a set of rules we established to help govern design decisions. Some of our rules included:

- Celebrate the beauty of the logs. There were several species, as cabin builders used whatever was available. Oak, chestnut, and pine were predominant and had survived the test of time.

- Use reclaimed materials as much as possible, either from the existing cabins or from sources in the immediate vicinity. We were able to reclaim 80% of the wood floors.

- Finish each cabin consistently with our interpretation of what might have been.

- Treat new materials and modern elements differently to clearly differentiate them from old ones.

- Express the structure honestly, so leave beams, joists, and new supports exposed.

[[[PAGE]]]

A Cohesive Design

Each part of the new home has its own specific language or code. While that might sound a bit ethereal, it was an important idea that needed to be understood in order for the project to be successful. All of the structures, from the roughest (the original 1794 log cabin) to the intermediate (the 1840 chestnut cabin) to the most refined (the 1856 frame addition) to the most current (the 2009 modern addition), have their own unique attributes. Instead of meddling with the elements in an effort to create a home with a universal feel from space to space, which would have been an entirely too literal form of cohesive design, we embraced and showcased the contrasting elements. The differences in these spaces and materials, which can be quite severe in certain instances, helped create a clear composition. Walking through the home, an observer can easily understand the age of each space and its relationship to the present and to the past.

SPECS:

Size: 2,400 sq. ft.

Bedrooms: 2

Bathrooms: 2-1/2

Design: David Haresign, Bonstra/Haresign Architects (www.bonstra.com)

Builder: Greg Foster, Timberbuilt Construction (www.timberbuiltconstruction.com)

Photography: Anice Hoachlander (www.hdphoto.com)

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid

Not So Big House

All New Bathroom Ideas that Work