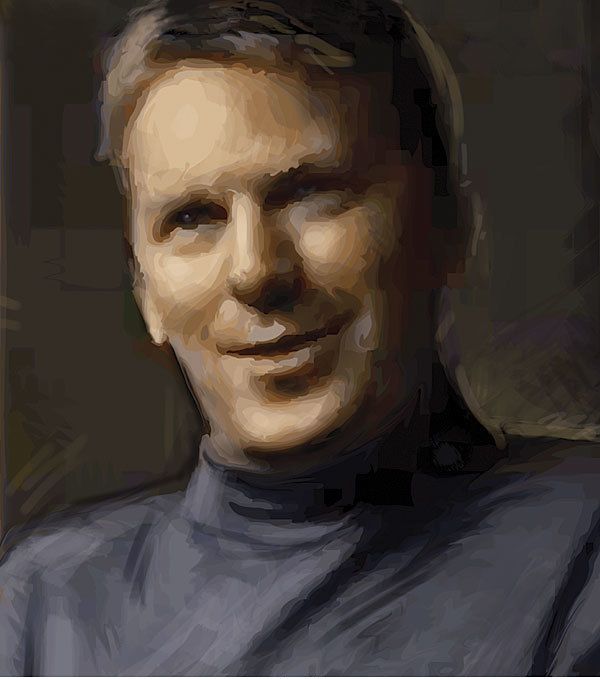

Tailgate: Cameron Sinclair, Advocate

The founder of Architecture for Humanity is working to improve lives through socially conscious design

What was the motivation behind your book Design Like You Give a Damn?

It started with a big lecture in California, and it was the same talk I usually give. For whatever reason, I was in a really passionate mood, and also quite angry because they had given every other speaker an hour and they had given me 15 minutes. I suddenly realized that in a profession, people trying to do humanitarian and socially driven work are seen as kind of like a happy-puppy story. At the end of my speech, I was being very passionate: “I don’t care if you work for me, I don’t care if you work for so-and-so, I just want you to design like you give a damn.” The audience gave me a standing ovation.

What does it mean to design like you give a damn?

For a residential architect, it’s not just the home, it’s the community around that home. The community feels a sense of joy that that building is there, and even more that next generations of people who buy that house will walk in and say, “This is an amazing space. I don’t know who the architect is, but they really understood what it means to live well.”

How would you define socially conscious design?

Being socially conscious is being aware—thinking about not just the client but the community, the neighborhood, the city. You don’t have to be an ardent fighter of climate change, but you have to think about stressed resources and the next 20 years.

What domestic projects is Architecture for Humanity is working on now?

We’re about to embark on a really big project on upgrading schools across America. We’re looking at ways to improve schools to make them safer, greener, a better environment. Our local chapters—we now have 53 chapters—are all working on domestic work across the United States. We are trying to help Harrisburg, Ill., because FEMA denied them funding for rebuilding after a tornado, so we’re working with people to make sure they get support in the recovery. We’re also doing a design competition on rethinking decommissioned military facilities around the world, including ones in the United States. We were inspired by all the military bases in San Francisco that are now housing developments and schools and community facilities. There’s a lot going on in the United States. We’re just not very good at publicizing it.

What project is most inspiring?

At the moment, our program in Haiti has been incredibly inspiring just because we went in very simply. We were funded by schoolchildren. We raised money through kids doing bake sales all across America, so we decided to start building schools. Now we have 40 architects working on more than 50 projects ranging from housing to schools to clinics. Every time I go to Haiti and see a project we’ve built, I’m blown away by the quality in the context. I mean, the school in Port-au-Prince is the best school in the Caribbean right now.

What’s your view of residential design in the United States right now?

I think it’s in a tough place economically. We as architects do a great job, but I worry that residential architects are taking a defensive role as the fall guy for the financial collapse of the housing market. Let’s look at architect-designed houses and see how they’ve held their equity versus the non-architect-designed houses and go on the offense. When you have a dinner in a well-built home, you don’t want to sell it short, whereas if you have dinner in a tract suburban home, no wonder you want to flip it. I want to flip it by the time I get to dessert.

Where is residential design going?

think residential architects in America, like Marlon Blackwell or Jeanne Gang, have decided to look at regionalism. There’s a regionalism and a uniqueness to their design that makes their architecture really strong. I think we should be wary of mediocrity through high design. If every house was the same hipster home, it would be mediocre.

I think people assume the architecture that I like, but I think aesthetics plays a secondary role when you create a magnificent space. In a weird sort of way, it doesn’t become as important when you create something that’s a loving, rich environment. That is something that we are trying to deal with. When we worked on the Gulf Coast, we built probably 600, 700 homes. I can tell you those homes were not the most beautiful homes, but those homes were built with love because the client was fully invested in that process.

Drawing: Jacqueline Rogers