Design a Classic Fireplace Mantel

Fireplaces are appreciated and sought after for more than just their practical uses. Architect Reid Highley gives three examples of how to detail a traditional fireplace mantel.

It’s not a stretch to say that the allure of the open flame is hardwired into the human psyche. Fire has been a part of human habitations for thousands of years. Initially relegated to an outdoor pit, fire moved indoors with the advent of fireplaces and quickly became the focal point in a house. Gradually, new technologies like cooking stoves and central heating made the fireplace functionally obsolete. Nevertheless, more than 50% of American homes still have one. Clearly, fireplaces are appreciated and sought after for more than just their practical uses.

As fireplaces evolved from purely functional devices to decorative highlights in the home, their mantels followed suit. Initially, mantels were a utilitarian feature, used to hang cooking utensils or support a candle. Later, their craftsmanship became a way to convey wealth and social status.

Traditional architecture in particular has a history of celebrating fireplaces through mantel design. From simple compositions of raised-wood panels to showy assemblies of ornate trim profiles, the options for detailing a classic mantel are endless. Using the architecture of your home and the characteristics of the room as a guide, you can begin to hone in on a design that will make your fireplace a showstopper. The three examples detailed here demonstrate just a few of the many possibilities for a classic mantel in a traditional home. Like any appropriate mantel, they will help to mark the historical importance that the hearth once played in the home.

A grand mantel for a formal room

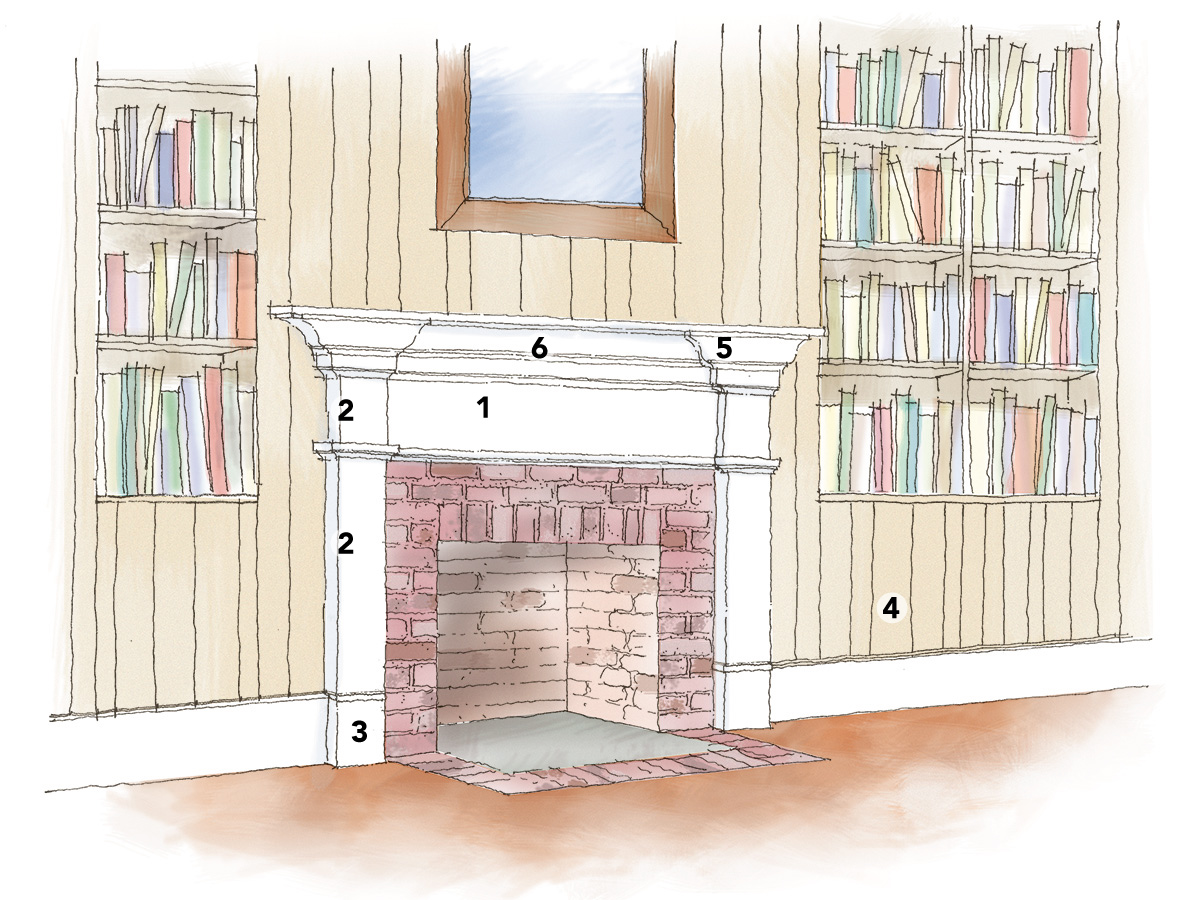

1. A tall, panelized overmantel stands proud of the surrounding walls and extends to the ceiling, highlighting the prominence that the mantel holds in the hierarchy of design elements in the room.

2. The frieze above the firebox is panelized in the same manner as the surrounding wainscoting, tying the room together visually.

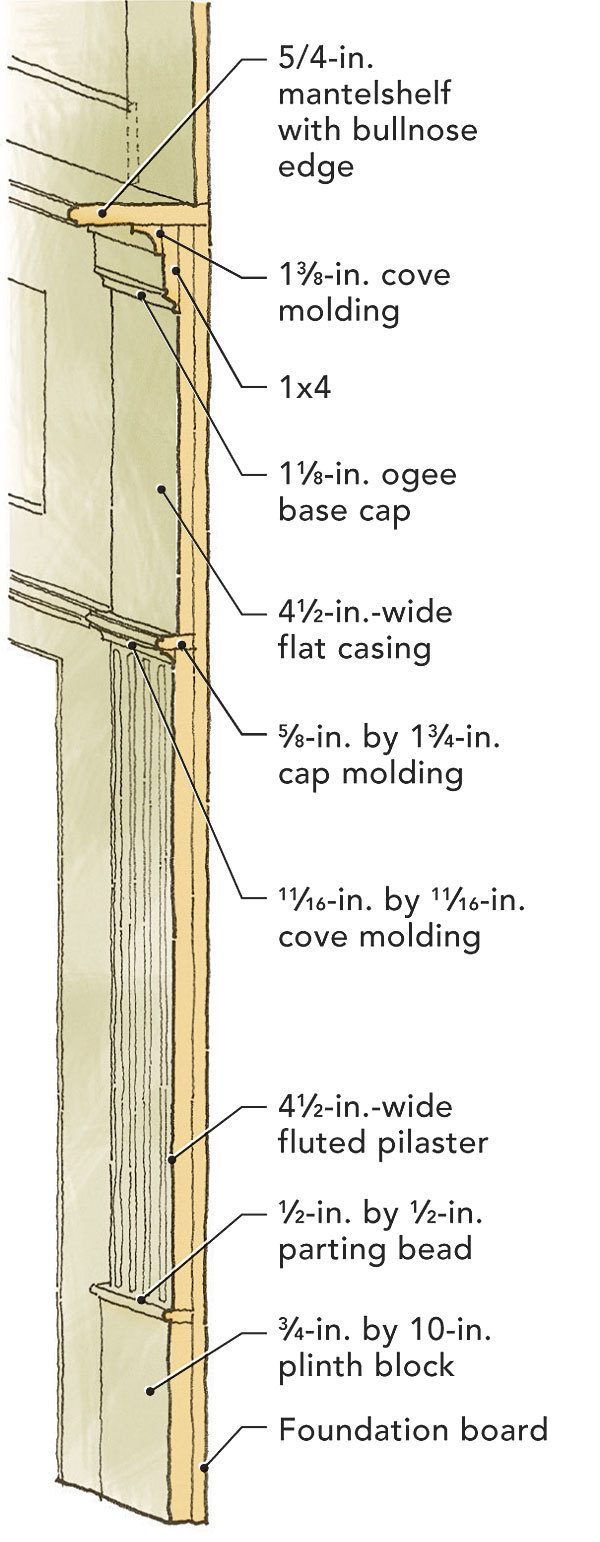

3. Set atop a wide foundation board framed with trim bands, the slender pilasters accentuate the vertical proportion of this tall fireplace without appearing spindly.

4. Each pilaster is topped by cap and cove molding that resembles a column capital. An astragal extends across the firebox opening much like the architrave of a classical temple.

5. A cornice built out of molding profiles supports a deep mantelshelf, perfect for the display of family treasures.

The traditional mantel pictured here is as classic as they come. On the end wall of a formal living room, the fireplace is reminiscent of those found in the colonial residences of early America. Flanked by two tall double-hung windows over wainscoting, the mantel stands proud and prominent in the room, extending its reach to the ceiling with a substantial overmantel. The overall assembly follows the guiding principles of the classical orders, with a plinth-block base and fluted pilaster columns supporting a panelized “frieze.” Tall, slender proportions befit the high ceilings and call attention to the fireplace as the focus of the space.

A simplified but formal alternative

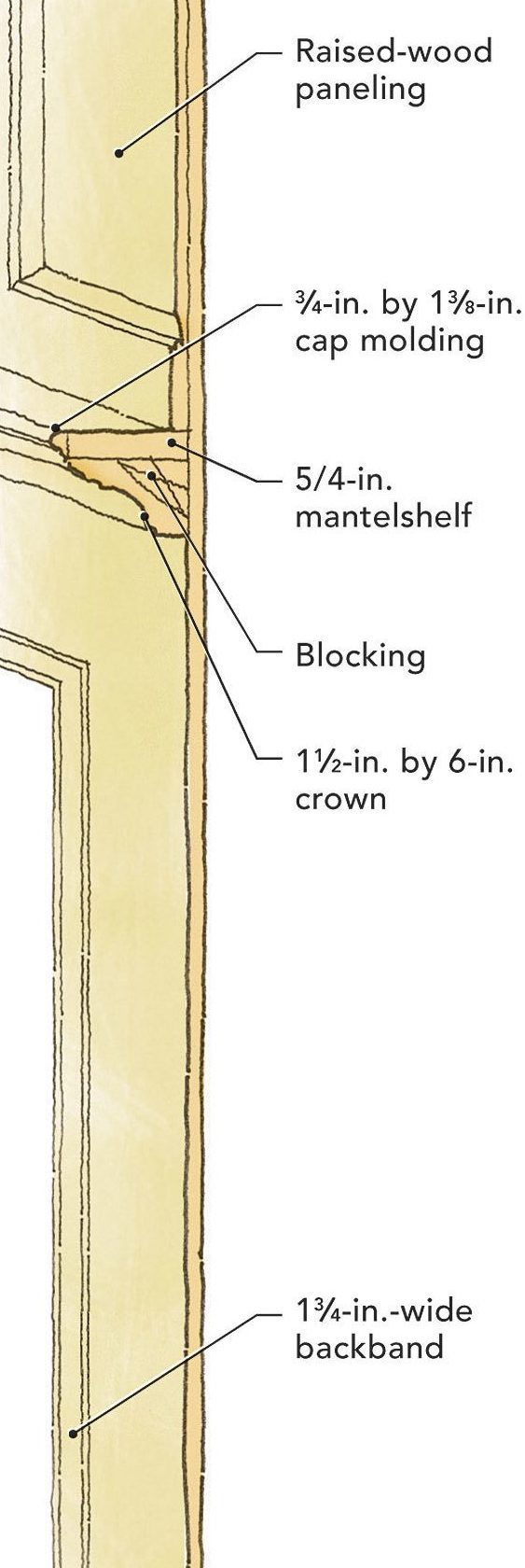

1. The deep profile of the mantelshelf gives it a sense of strength even without a supporting structure beneath it.

2. The transition from the wood wall paneling to the face of the firebox is highlighted with a slightly projecting trim band.

3. Carefully orchestrated alignments between the raised panels and the trim around the firebox draw the wall’s composition together visually.

4. Shown here painted, this style of mantel is also appropriate for clear finishes.

5. The varied panel widths above the mantelshelf create a defacto overmantel, a fine spot to hang a painting.

This mantel is a simpler option for formal surroundings. Rather than sitting atop pilasters, the mantelshelf floats free. Built up from multiple pieces of trim, the shelf is thick and substantial, and is the focus of an otherwise understated composition. A basic trim band bordering wall paneling frames the plaster firebox surround. The wall surface is composed of raised panels divided into well-proportioned rectangles that correspond to the dimensions of the fireplace. In this way, the fireplace acts as a focal point for the room without needing to assert itself with complicated architectural details.

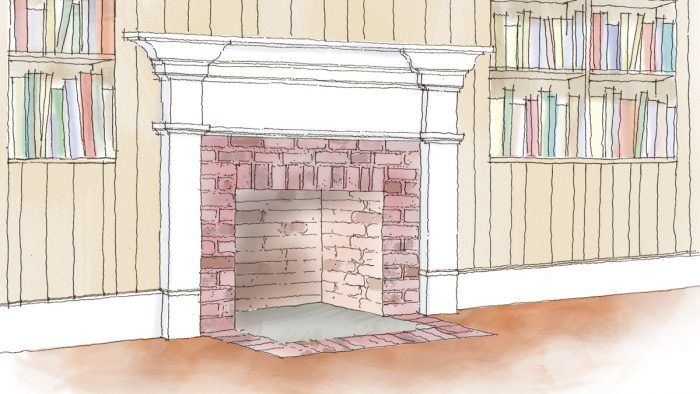

A casual interpretation

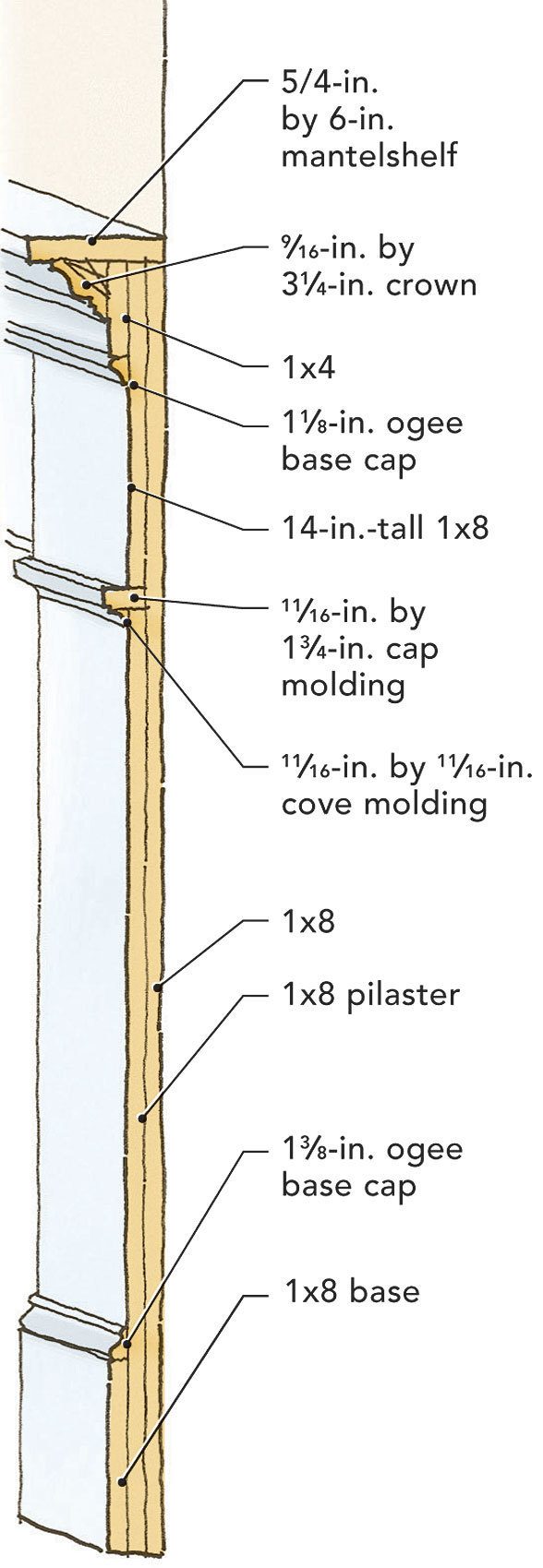

1. A smooth, unadorned frieze matches the pilasters and feels appropriate for the informal architecture of the room.

2. The pilasters and frieze are aligned, as they should be in any classical mantel composition.

3. Wide, flat boards are used for the pilasters, creating a sturdy yet simple base for the mantel.

4. The mantel’s color differs from that of the surrounding wall surface, making it a focus for the room.

5. A tall, deep cornice below the mantelshelf conveys a sense of strength and substance.

6. The crisp profiles of the mantel stand in contrast to the busy visual texture of the bookshelves.

This less-formal mantel is most suitable for a cozy den or an office. Rather than being on an end wall, the fireplace is in the center of the house and projects into the room. Cabinets and bookshelves in the resulting recesses take full advantage of this arrangement, creating handy storage in a space that might otherwise go unused. The surround is relatively simple, and its low overall height is proportional to the size of the room. The crisp white finish contrasts with the visual texture of the wood wall, painted a pale beige. This color contrast sets the mantel apart from its surroundings and draws the eye to the center of the room, toward the firebox opening. The redbrick surround is suitably simple and provides a subtle textural contrast with the mantel.

Code-compliant design

Wherever fire is concerned, safety is a primary consideration. Before designing a mantel, check with your local code authority to verify material and clearance requirements. The International Residential Code states that you must keep all combustible materials a minimum of 6 in. from the firebox opening. In addition, all combustible materials fewer than 12 in. from the firebox can project no more than 1⁄8 in. for each inch of distance from the opening. So, for example, a wooden pilaster with an edge 8 in. from the firebox can be no more than 1 in. thick.

Drawings: Jim Compton