Energy-Saving Lightbulbs

Incandescent bulbs are changing quickly to keep up with more-efficient, longer-lasting competitors

If you haven’t noticed, there’s a lightbulb revolution in full swing, marching double-time to an energy-efficiency beat. Incandescent bulbs, once the king of home lighting, are relinquishing more and more shelf space to bulbs such as CFLs (compact fluorescents) and LEDs (light-emitting diodes). These technologies aren’t new, but they have gained far more momentum thanks to recent federal legislation (see below).

Today, these energy-conserving bulbs come in so many shapes and sizes, with prices all over the map, that a trip down the lightbulb aisle can leave you bewildered. Many shoppers have resorted to buying a bulb, bringing it home to try it out, and then returning it if they don’t like the color of the light, its reaction time when switched on, or its behavior when dimmed. For this article, I knew I’d have to try as many bulbs as I could in my home. I couldn’t possibly test all of the various brands and sizes, so I focused on bulbs that were available at the stores in my area of Austin, Texas. I also limited myself to screw-in replacement bulbs—the type in table lamps, ceiling lights, and recessed cans.

Incandescent bulbs have been warming our faces with their light (and their heat) for so long, though, that considering any substitute is, for some, a Herculean task. Unflattering light color, early burnouts, and high costs kept many consumers from accepting earlier versions of energy-saving bulbs. If you’re one of those skeptics, I believe that today’s better bulbs will change your mind.

IT’S NOT A BULB BAN

Over the past few years, there’s been considerable ranting about a government plan to force the everyday lightbulb into extinction. Anecdotes tell of folks hoarding 100w bulbs to avoid having to switch to energy-saving alternatives. Contrary to that rumor, incandescent bulbs have not been banned, but the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) of 2007 demands that they be more energy efficient.

The act, which is intended to move the United States toward a higher level of nationwide energy efficiency and security, includes changes to the performance of our cars, appliances, and yes, our lightbulbs.

The big shortcoming of a traditional incandescent bulb is that it converts only about 1⁄10 of incoming energy into visible light; the rest is emitted as heat. With billions of standard screw-in light sockets in homes worldwide, that’s a staggering amount of wasted energy. The goal of the EISA legislation is for every lightbulb, including incandescents, to convert a substantial portion of electricity into visible light. Because standard incandescents don’t measure up, improvements are coming. Incandescents will remain, and they will still cast bright, pleasing light. They’ll just do so more efficiently.

The law targeted 100w bulbs in January 2012 (California began the switch in 2011), requiring that they use 27% less energy while remaining approximately as bright as they always had been. Now, instead of 100-watters in stores, you’ll see 72w bulbs listed as “100w equivalents.” In 2013, ordinary 75w bulbs will begin to phase out; 40w and 60w bulbs are targeted for 2014.

HALOGEN:

PROS: Inexpensive; great color-rendering index (CRI) for most home environments; easily dimmable; no mercury or semiconductors for disposal; huge range of shapes and sizes; full range of beam dispersion, from spot to flood to omnidirectional; good on/off cycling performance; great for motion-sensor lights; not temperature sensitive, so excellent for appliances (ovens, refrigerators, freezers).

CONS: Low efficacy; excessive heat, which adds to cooling costs in summer; short bulb life; poor choice for fixtures with limited access or very high ceilings; can damage shelf contents with heat when used as undercabinet lighting; vibration and impacts can break filaments.

Jim Wehtje

CFL

PROS: High efficacy; long life; fairly inexpensive; excellent omnidirectional light diffusion; good range of color temperatures; small and lightweight.

CONS: Start-up delay for some types; contain mercury (less than 1⁄100 the amount in a mercury thermometer); poor starting in very cold environments (although bulbs with special cold-weather ballasts are available); dimmable CFLs may require special dimmers; frequent on/off cycling, such as with outdoor lights controlled by motion detectors, shortens lamp life; possible incompatibility with photocells such as those on motion-sensing outdoor floodlights.

Jim Wehtje

Next-gen incandescents

After the federal legislation was passed, makers of incandescents moved quickly to stay on the playing field. With billions of screw-in bulbs sold in the United States alone, the stakes were too high to sit on the bench. Complying with the new rules was an easy transition because the answer was a longer-life bulb that they’d had on the market for decades: the quartz halogen.

By encasing a quartz-halogen light capsule inside an ordinary glass shell and then adding a screw base to it, they were able to create a more efficient bulb that looks and feels like a regular incandescent, producing the soft-white light that people love. As with all incandescents, light is emitted when the tungsten filament inside the capsule heats up and glows. The difference with these bulbs is that halogen gas surrounding the filament allows it to burn brighter and longer than the tungsten filament in a standard incandescent bulb.

Unlike fluorescents, halogens contain no mercury, so you can throw broken and spent bulbs into the regular trash. They are fully dimmable, but they burn very hotly. Expect to feel the warmth when sitting near one.

Negative reviews about these new incandescents are mostly about early burnouts, especially if the bulbs are subjected to vibrations or are bumped while in use. However, when given my rudimentary bump test, the halogen bulbs I tested were on par with ordinary incandescents. They are, however, susceptible to early failure when the electrical current surges above 120v frequently, but this is true for all incandescent bulbs rated for 120v. Electricians here in Austin routinely supply bulbs rated for 130v to prevent this type of failure.

The light emitted by these bulbs is familiarly incandescent, with soft, even diffusion. Brightness is also good despite the lumen ratings being somewhat less than those of traditional incandescents. They cost about twice as much as the older incandescents, but they should last longer and pay for themselves in energy savings.

LIGHTBULB LINGO

Listed in lumens per watt, efficacy is the fuel efficiency of a lightbulb. It’s a measure of how much light is produced from the electricity going to a bulb; higher is better. For example, a standard 75w incandescent bulb producing 1100 lumens of light has an efficacy of about 15 lumens per watt. By contrast, a 22w CFL with the same light output has an efficacy of 55 lumens per watt—almost four times as great.

LIGHTBULB LINGO

The common lightbulb is known in the industry as an A-19 lamp. The A signifies the familiar shape of a general-service bulb, and the 19 signifies the bulb diameter in eighths of an inch. An A-19 has a diameter of 23⁄8 in. at its widest point. Other bulb shapes have different designations, such as R (reflector), G (globe), and T (tube). A T-8 fluorescent tube is 1 in. dia., and an R-30 flood measures 33⁄4 in. dia.

Compact fluorescents

A CFL bulb produces light in the same way as its linear forefather: Phosphorous coatings inside the tube glow brightly when electricity runs through the bulb. The only difference is that a CFL folds or twists the thin glass tube tightly to save space without sacrificing the tube length necessary to maximize the light output.

First-generation CFLs had several shortcomings. They were expensive, slow to come to full brightness, and quite heavy when equipped with magnetic ballasts. In addition, they weren’t dimmable, their bulkiness limited their use around the house, and their color was considered too harsh.

Today’s CFLs deliver faster starting, no flickering, reduced weight, and dimming capabilities. Most CFLs render colors much more accurately than fluorescents did years ago, which is attributable primarily to better phosphorous coatings inside the glass. Plus, improved production methods have lowered costs dramatically and have enabled smaller bulbs to fit a wider variety of light fixtures.

Before LEDs came on the scene, CFLs were the best option available for energy-saving lightbulbs. I’ve had many of them in my home and studio for years because of their high efficacy and low cost. Yes, some have burned out early. Yes, I’ve had to return some for poor color quality. Until the cost of LEDs comes down substantially, though, I will continue to use them. I shave by their light every morning, and I love having the R-30 floods in the recessed cans of my high ceilings, where access to the bulbs is a challenge. They give a pleasant, diffuse light with less heat, saving work by my air conditioner for seven months a year. I’m used to the slow start as they warm up, a trait that is more exaggerated with floods than with other CFL bulb shapes.

I don’t normally have CFLs on dimmers, but I tested three for this article because I’ve heard the complaints. As recommended, I did an initial two-hour “burn in” at full brightness before dimming them. They all performed well, with good color and smooth, gradual dimming without flickering. However, it may have been a coincidence that my Lutron Diva dimmer and house wiring were compatible with the bulbs; other compatible replacement dimmers are also on the market.

Despite their big energy savings, fluorescent lightbulbs face two big obstacles to maintaining market share against the onslaught of LEDs. The first, color, is an old thorn. The cool-white light of some fluorescents felt harsh to many homeowners, and even though color-corrected CFLs have been around a long time, not everyone knows about them. In fact, some of my clients are convinced that fluorescent light is suitable for their garages but not their homes.

The second hurdle is fairly new: the mercury scare. As they always have, fluorescents contain tiny amounts of mercury, a toxic heavy metal. A broken fluorescent bulb can leach its mercury into a landfill or vaporize it into your home’s airstream. Hazmat teams are not required if you break a fluorescent in your home, and cleanup instructions are found easily on the internet. When your CFLs burn out, check your trash collector’s policy on household hazardous-waste collections, or visit Earth911.com to find retailers with recycling programs near you.

LIGHTBULD LINGO

To measure a bulb’s ability to reproduce colors as they would appear under natural light, the industry uses a color-rendering index (CRI) that is based on a scale of 1 to 100, with 100 assigned to the way colors appear under incandescent lighting. Halogens have a 100 CRI by default, but when you can (it’s not always listed on the package), look for a CRI of 80 or higher when shopping for fluorescent and LED bulbs.

LEDs are pricey, but promising

Although they are a new form of energy-saving lighting for our homes, light-emitting diodes have been used for many years as colored lights in electronic displays, indicator lights, traffic signals, flat-screen TVs, and other places. Also known as solid-state lighting, LEDs produce light when electricity passes through semiconductors, a process called electroluminescence. Different frequencies produce different colors of light.

Key to solid-state lighting finding its way inside our homes has been the development of white LEDs that emit warmer tones. Inexpensive white versions emit a cool bluish cast—perhaps acceptable for an outdoor landscape light, but not for a reading lamp. Mixing red, green, and blue LEDs is one way of producing white light, but the bulbs found in stores mostly combine phosphorous coatings with blue LEDs to make the soft white light we crave.

Achieving omnidirectional light diffusion from an LED bulb was also a challenge, because individual solid-state diodes emit light in only one direction. Manufacturers have met the challenge with configurations of diodes and diffusers that resemble the shape of a standard lightbulb. Still, some LEDs look odd, and their futuristic appearances take some getting used to.

Heat dissipation is critical to proper operation of an LED bulb. Most have extra surface areas, usually arrays of fins, which act like radiators to conduct heat away from the temperature-sensitive circuitry. Some newer models incorporate minuscule fans and diaphragms to circulate air. Switch, a California manufacturer, designed a liquid-filled dome into its bulb to keep the diodes cool. Because excess heat will kill LEDs, they should not be used in enclosed light fixtures. Some makers say that their bulbs should not be used in airtight, insulation-contact recessed cans, either.

Under today’s laws, LEDs are not classified as hazardous waste and can be disposed of in typical landfills. However, a 2011 study by the University of California, Irvine, recorded small amounts of contaminating metals such as lead, nickel, arsenic, and copper leaching from the pulverized residue of LEDs from traffic signals, car brake lights and headlights, and Christmas-tree lights.

Although prices are expected to drop significantly in the next two years, the biggest barrier for LEDs is their price. LEDs are expensive to make and are priced accordingly. Depending on the type and brand, expect to pay $10 to $50 for a single bulb. When a bulb costs that much, it better be outstanding in every way: bright and with impeccable color, perfect dimming, and an amazingly long life. Because LEDs are a young technology, they won’t all perform this well. There will be some duds in every batch, and some manufacturers will cut corners to keep down costs. If you get a clunker that dies early, buzzes, or dims poorly, exchange it or return it for a refund. Warranty periods vary from three to five years and are stated on the packaging.

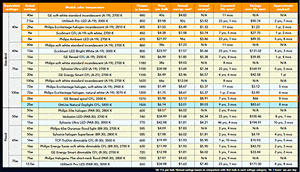

COLOR BY KELVIN

Color temperature is part of the data required by the Federal Trade Commission to be on packaging to help consumers know whether a bulb’s light output will appear “warm” (a yellowish glow), “cool” (a white or blueish-white cast), or somewhere in between. Because these terms are subjective, a numerical rating measured in degrees Kelvin (K) is used for accuracy. The bulbs listed in our chart are color-coded based on color temperature differences, which are detailed below.

Paul’s picks

(left to right, and highlighted in chart)

Philips EcoVantage halogen incandescent

Power rating: 29w

Color temperature: 2810 K

Output: 405 lumens

Expected life span: 1000 hours

Price: $1.50 each

*Annual energy cost: $3.49

In use: Very similar light color to regular incandescent; dimmable. This is my favorite energy-saving bulb for vanity lighting. My wife has no idea that I swapped out her beloved 40w “grocery-store lightbulbs” for these bulbs.

Philips Ambient LED

Power rating: 8w

Color temperature: 2700 K

Output: 470 lumens

Expected life span: 25,000 hours

Price: $21.97 each

*Annual energy cost: 96¢

In use: Beautiful yellow light, even slightly warmer than the GE 40w incandescent; seeing yellow plastic in the off mode may turn away some buyers; dimmable. If you like that campfire-cozy feeling in the evenings, this is a winner.

GE Reveal spiral CFL

Power rating: 26w

Color temperature: 2500 K

Output: 1570 lumens

Expected life span: 8000 hours

Price: $5.98 each

*Annual energy cost: $3.13

In use: Not as bright as the Philips 100w incandescent, but the warmest color I tested, hence the 2500 K listing; warmer than the incandescent but not better color, as there is still an ever-so-slight pink cast; not dimmable. Lumens and color rival old 100w bulbs, but without all that heat.

(*At 11¢ per kwh)

Paul DeGroot is an architect in Austin, Texas. Photos by Rodney Diaz, except where noted.