HVAC stands for heating, Ventilation, and air-conditioning, right? In general, the ventilation for Texas homes has come from one source: infiltration. What is infiltration? This is the air that leaks in around windows, doors, outlets, etc. Most Texas houses have ducts in their unconditioned attics, and when the furnace fan kicks on, those ducts leak 30 cfm, 60 cfm, 90 cfm of air into the attic. That puts the house into a negative-pressure situation, and that pressure is relieved by air leaking in around recessed cans in the ceiling or around vents or outlets on exterior walls. Texas houses are generally highly leaky structures. Infiltration is a poor way to ventilate a home. This method brings with it all the pollutants from the air source. Have you ever noticed dust marks on the drywall around ceiling registers? That’s probably dust and fiberglass deposited by attic air leaking in from around the duct boots. The air leaking in from infiltration is usually hot, humid, and potentially polluted with pollen or other allergens.

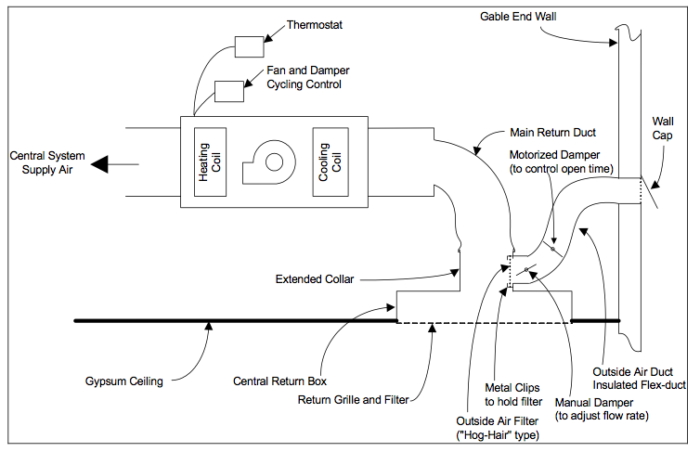

Good: Central-fan integrated ventilation with continuous exhaust

This is my Risinger Homes standard and this system works very well.

- Airtight ducts pressure-tested to

- All ducts in the conditioned space of the house

- 4-in. to 8-in. fresh-air duct to the return side of the furnace fan

- Pleated media air cleaner MERV 10+ (Video Review of the Aprilaire I recommend)

- Balancing damper for flow adjustment

- Motorized damper with fan cycle control Aprilaire Model 8126

- Panasonic WhisperGreen exhaust fan continuous duty. I like the FV-08VKS3 model.

- Portable dehumidifier plumbed and set for 50% relative humidity (Building Science Corp Article on this)

Better: Good system plus ventilating dehumidifer

This is the same system as above but adds an Ultra-Aire ventilating dehumidifer to the HVAC system (instead of the portable plug-in model in the good system). The fresh-air pipe goes to the dehumidifier first, then to the return side of the furnace for distribution. This is really the premier system in terms of comfort for a house in our hot/humid climate zone. This system is a bit more expensive but is vastly more comfortable for my clients than any house they’ve lived in before. See this video for an overview of a house with an Ultra-Aire XT150 installed.

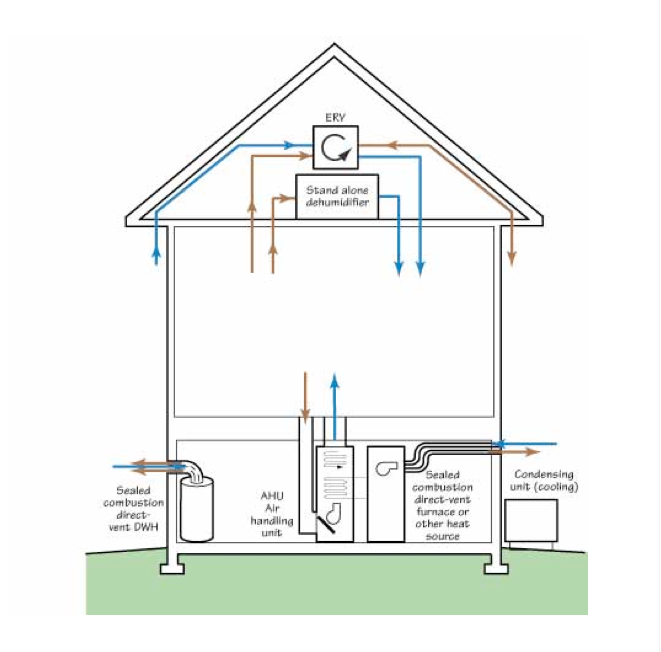

Best: Better system plus the addition of an ERV and HEPA filtration

In this system, we uncouple the dehumidifier and the ERV so that they are separate and fully independent ducted systems not connected to the furnace. This system has several advantages. The ERV is able to move some of the moisture (energy) between the incoming/outgoing airstreams so that the fresh air is dehumidified before entering the house. The ERV has a small efficient fan to bring in outside air and to exhaust stale air. The ERV has separate controls and can have a carbon/particle filter to remove pollen and ozone before entering the house. HEPA filtration is also easy to add to the ERV if necessitated by clients with asthma or compromised immunity.

You will notice that in all three ventilation strategies, there is a supplemental dehumidification component. I found this interesting exerpt from a Building America Ventilation Guide in relation to our humid/hot climate and the ASHRAE 62.2 ventilation standard:

If the target ventilation rate is to be maintained in a humid climate, active dehumidification should be considered. Consider a 2500-sq-.ft. four-bedroom home. The required ventilation rate would be 63 cfm. In a hot-humid climate like Sarasota, Fla., according to the ACCA Manual J Table 1, the outdoor 1% summer design condition is 92°F with a coincidental wet bulb of 79°F. The moisture content of the air is 129 grains per pound of air. A pound of air occupies about 14.3 cubic feet. So our target ventilation will move about 4.4 (63/14.3) pounds of air into the building per minute. Also, with it comes 5676 (4.4×129) grains of moisture. In an hour, we have transported 340,560 grains of moisture. There are 7006 grains of moisture in 1 lb. of water (roughly one pint). Thus, the target ventilation will bring in 48 pints or 3 gal. of water during one hour of operating time; that is equivalent to moving 72 gal. of water through the home in a 24-hour period.

With no active dehumidification, the home accumulates water until the grains per pound of air indoors is equal to the grains per pound of air outdoors. In the Sarasota, Florida, area where the moisture levels are 129 grains per pound of air outdoors, it will be 129 grains per pound indoors. If the home had 8-foot ceilings, it would contain 20,000 cubic feet or about 1,428 pounds of air. At 129 grains per pound, there would be about 26 pints of water in vapor form in the air at all times. If the AC system was oversized and it could easily maintain 75°F with very little run time, the indoor relative humidity would be 98% and the dew point would be 74°F.

Thanks for reading this pretty geeky post! I also want to thank Joe Lstiburek and the good folks at Building Science Corporation who have some amazing building-science research all posted free for the world to learn. I wish you the best in your building endeavors.

Remember: Build tight, ventilate right!

Best,

Matt Risinger

Risinger Homes is a custom builder and whole house remodeling contractor that specializes in Architect driven and fine craftsmanship work. We use an in-house carpentry staff and the latest building-science research to build dramatically more efficient, healthy, and durable homes.

Be sure to check out my video blog on YouTube.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

Musings of an Energy Nerd: Toward an Energy-Efficient Home

All New Bathroom Ideas that Work