Bright House Images

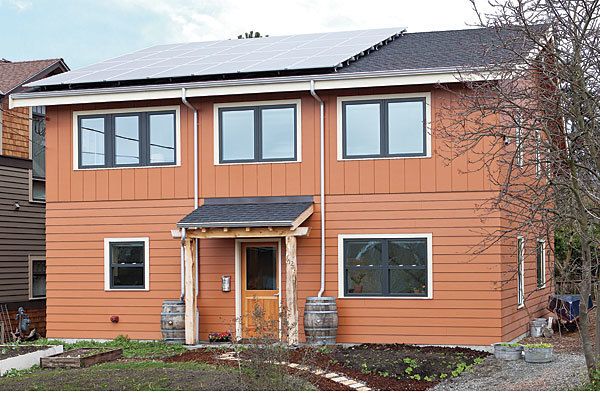

“Mom and Dad must have paid for that one,” our neighbor said, apparently assuming that the net-zero energy house my wife, Alex, and I had just built and moved into had cost a small fortune. I told him that our house was much less expensive than most new houses in the city and would make more energy than it used, but I could see by the way he was eyeing the photovoltaic (PV) panels on the roof that he didn’t believe me.

My neighbor, like many people I talk to, think building green costs a lot more than standard construction. Who can blame them? The most publicized “green” homes are usually big, modern, and totally inaccessible to the average homebuyer.

Alex and I couldn’t afford an expensive home. In fact, we couldn’t even afford an average new house. The housing bubble had burst, banks weren’t lending, and we were newlyweds who probably had no business thinking about building a house, let alone Seattle’s first net-zero house. At the same time, we were committed to creating a home that would save us money on energy bills for years to come.

Balancing money and building choices

We put our money into the south-facing lot and into making the shell of the house tight and the R-values high. We figured we could upgrade the cosmetics later, but we knew that it would be extremely expensive to replace all of our windows or to undo a poor choice in insulation. We chose efficiency and practicality over glam.

We bought plans from Ted L. Clifton, whose nearby company, Zero Energy Plans, takes a pragmatic approach to reaching net zero. The 1915-sq.-ft., three-bedroom, two-story house was built of structural insulated panels (SIPs) that netted R-26 walls and an R-42 roof.

To save money, we eliminated things we didn’t need. Not owning a car, we saw no need for a garage. We chose a slab foundation instead of a basement, which also allowed us to eliminate flooring on the ground level. Instead, the builders acid-stained the concrete, resulting in a beautiful, durable floor.

We also omitted a heat-recovery ventilator (HRV), which is standard in tight, energy-efficient houses. Instead, our house has exhaust fans in the laundry, the kitchen, and the bathrooms. Switching on the powerful exhaust fan in the kitchen also activates a HEPA-filtered supply fan that sends fresh air to all three bedrooms and the living room. An HRV offers energy savings as well as ventilation, but we found that adding a few more watts of PV power was a more cost-effective way to achieve these savings.

The only heat source on the second floor is an electric radiant mat under the bathroom floor. With the living room open to the upstairs, air heated by the ground-floor radiant slab warms the upstairs bedrooms. We keep the house at 69°F in the winter, and the air stays at a comfortable 55% relative humidity. The house is cool in the summer without air-conditioning. One year after we moved in, our PV system had produced a surplus of about 1400kwh.

How much did this cost?

Ted Clifton Jr., our designer’s son, was our general contractor. We liked how he made use of inexpensive materials that also gave his houses a solid feel and a pleasing look. We did some work ourselves, such as painting the trim and installing the reclaimed wide-plank fir floors upstairs. One way we saved a considerable amount of money was to handle all the permitting and paperwork.

We went into this project with the goal of keeping its cost about the same as that of a town house in the same neighborhood. The land cost $180,000. Construction, the PV system, taxes, and permits added another $237,000. (The 6.4kw PV system cost about $32,700 before a $9000 federal tax credit and a Washington state solar-production credit, which will pay out another $9000 or so over nine years.) The grand total came to about $399,000, or $124 per sq. ft. ($114 if you count the rebates and incentives). Plus, we won’t be paying for energy, which will save us about $150 per month.