Self-Taught MBA: Building Abundance in a Tough Market

Forming mutually-beneficial relationships with a loyal group of subcontractors is a sure-fire way to keep construction costs in check, keep qualtiy high, and build a good reputation

When I decided to build and sell the lowest-price house on the market, I knew it would be a challenge to get subs on board at the prices needed to accomplish this. If I simply drew the plan and asked for proposals, awarding the jobs to the cheapest bidder in every trade, I would likely still strike high of the target, and have to settle for “you get what you pay for” materials and workmanship. Taking a different approach, I proceeded to build the least expensive house on the market with the same group of subs and at a reasonable profit for nearly ten years running.

The approach I took involved an intricate series of steps, aiming toward the complete satisfaction of all parties in negotiation. Achieving this ambitious goal required building alliances and inspiring teamwork, and this is why we call the third method of negotiation, and the last installment in this series on making deals, “collaborative negotiation.” It’s the most difficult, but also the most rewarding.

Building a Competitive Cohort

Because it takes a long time and a lot of creativity to build a truly collaborative business relationship, the only people that do it share long-term interests. It makes no sense in a one-off transaction. It’s the type of negotiation you would engage in with a loyal group of subcontractors, unless you wanted to bid out every job.

In order to be successful at establishing a relationship that’s as beneficial for you as for your subs, you’ll have to do more than simply hire the same folks again and again. If you’ve been doing that, you will no doubt have noticed your costs steadily climbing. You’re a good customer, appreciated for helping put the plumber’s kids through college, but you don’t share a clear mutual interest.

My interest was offering the lowest-price, highest-quality house on the market. My subs were not enamored of the idea, however; they saw very a low-margin venture at best. I described to them, one by one, a threefold plan: We would design a house together that we could build as inexpensively as possible and that would be a reliable, high-volume product in a crowded and competitive real-estate market. We would build the same house again and again to develop a high level of individual efficiency. We would work together as a team to orchestrate a streamlined, stress-free job site.

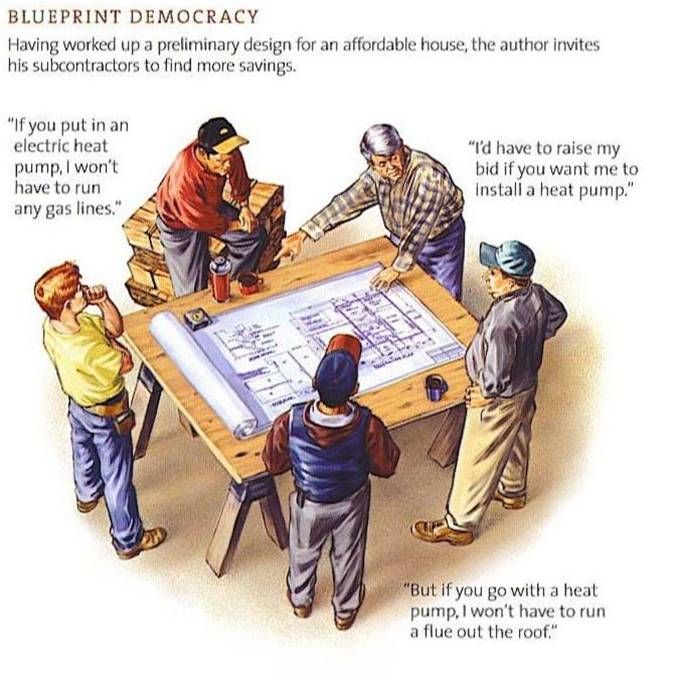

Not everyone agreed, but I only needed one sub for every trade. Several of the guys had already mused on how they would design an efficient plan, and they looked forward to the chance to test their theories. We met many times, often as a team, until we had a basic blueprint. The project never went out for bid, but the prices came in even better than I hoped. We sold our first iteration of what we called the “A” plan for $75,000 in 1995. By 2005, the price had climbed to $98,000, but it was still the least-expensive three-bedroom house available by a long shot.

Competing builders sometimes swiped plans from the job site and then tried to reproduce our success, only to discover that their costs exceeded our retail price. Although the design itself embodied efficiency, it was the buy-in of the team we developed over time that allowed us to compete against the market, rather than as individual interests against each other.

Full-Contact Collaboration

Hardball collaboration requires open, honest communication and the relentless search for creative solutions and alternatives to financial conflict. Instead of charging more, subs look for ways to improve efficiency. Instead of twisting arms to get better prices, the builder finds ways of reducing material costs and labor time by redesigning floor plans and improving procedures. Over the years, we continuously worked to streamline and perfect our little plan for the benefit of all. Prices still went up, but slowly, and not by much.

To achieve price stability within an inflationary economy, team members needed not only to cooperate but to speak up and demand solutions. This is drastically different than demanding more money. Because we all shared one goal (offering a house nobody could compete with), instead of defeating the team effort by raising prices, we struggled within the team to continuously lower everybody’s costs.

Collaborative negotiation requires that parties place a high value on the relationship itself, and not just the transaction at hand. To achieve this, parties have to agree on the principle of mutual benefit and find a unifying goal. Transparency becomes critical, as do giving information before it’s requested and suggesting alternatives whenever a solution does not satisfy all the parties involved.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Affordable IR Camera

Reliable Crimp Connectors