What does “green building” really mean? You can choose trendy interior-finish materials like bamboo flooring or earth plaster, but the choices you make on interior finishes are unlikely to matter much from an environmental perspective—especially compared to the energy-efficiency decisions that affect the whole house.

Magazines, books, and websites offer conflicting information. One might tell you that a green home should include sprayfoam insulation, a tankless water heater, and a geothermal heating system. Then you visit another website, where you learn that spray foam is a dangerous petrochemical, tankless water heaters are overpriced gadgets, and “geothermal” systems are not really geothermal.

At this point, you’re probably tempted to go back to the website that told you to buy a tankless water heater. At least that advice was easy to understand.

Here, I’ll help you to focus on what really makes a home “green.” If you’re intrigued by what you read here, visit Fine Homebuilding’s sister website, GreenBuildingAdvisor.com, for more in-depth advice.

Design green to build green

A green home is small. Smaller homes consume fewer resources to build, maintain, heat, and cool. If you follow good design principles, you can make a small space attractive, durable, and eminently livable for your family. Aim for a compact shape with few ells, bays, and bump-outs; this minimizes both material use and the amount of heat-losing exterior walls relative to the interior space.

Orient the long axis of the house in an east-west direction to control solar gain best. In most U.S. locations, it makes sense to include more windows on the south side than the north side. (This advice doesn’t apply in hot climates or in the Southern Hemisphere, however.) Wide roof overhangs shade windows from unwanted summer-heat gain and offer the siding more protection from rain and snow, possibly increasing its life. Make sure that the roof overhangs are adequate.

Build tight and insulate right

The most important way that you can improve the energy efficiency of a house is to reduce air leakage. You are unlikely to end up with a tight house unless you choose a designer who understands the need for airtight construction methods and unless you choose a builder who has already built a tight home that has been tested with a blower door. (Blower doors are diagnostic tools that help to quantify and identify the location of air leaks.) Insist on a blower-door test. If possible, include an airtightness goal in the job specifications.

The second most important way that you can improve the energy efficiency of your home is to specify insulation with a higher R-value than that required by your local building code. Building codes specify minimums, not best practices.

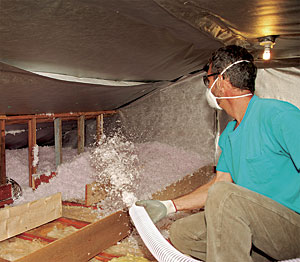

Almost any kind of insulation can be made to work, although some types—most notoriously fiberglass batts—are difficult to install well and usually perform poorly. Among the most popular insulation materials specified by green builders are cellulose (made from recycled newspapers) and mineral-wool panels, which can be substituted for rigid-foam insulation on the outside of wall sheathing. Although some green builders try to minimize the use of foam insulation, it’s hard to beat rigid foam or spray foam for certain applications, such as under a concrete slab or on the interior of a basement wall. Some types of foam insulation use blowing agents that contribute to global warming or fire retardants that raise environmental and health concerns.

The third most important way that you can improve the energy efficiency of your home is to specify windows with the right type of glazing. This means that you want windows with a lower U-factor. (U-factor is the inverse of R-value, so the lower the U-factor, the better the insulating value of the windows.) In hot climates, you should choose windows with a low solar-heat-gain coefficient (SHGC) for the east and west sides, where low-angle morning and afternoon sun shines directly in. Designers in hot climates should try to keep west-facing windows to a minimum, or they should include a wide porch on the west side of the house. In cold climates, you should choose windows with a high SHGC, especially for the south side. For comparison purposes, U-factor and SHGC can be found on most window labels.

Be smart with HVAC

Locate ducts inside your home’s thermal envelope—the spaces that you heat and/or cool. Do not allow your designer or builder to locate ducts, even insulated ducts, in a vented crawlspace or a vented attic.

Tight homes need a mechanical ventilation system. There are three basic choices: an exhaust-only system consisting of one or two high-quality bath fans; a supply ventilation system that introduces a little fresh air into your furnace ductwork; or a balanced ventilation system that includes a heat-recovery ventilator (HRV) or an energy-recovery ventilator (ERV). Any one of these systems can work well.

Because domestic hot water cools down with long runs of piping, designing a compact piping arrangement with a layout that places your bathrooms as close as possible to your kitchen matters more than the type of water heater you choose. Installing a solar water heater rarely makes financial sense.

If you have followed the above principles, your heating and cooling needs will be minimal, so you won’t need an expensive heating or cooling system. That’s why you probably won’t need a ground-source heat pump (sometimes called a geothermal system) or a radiant-floor distribution system. Hire an engineer or a certified energy rater rather than an HVAC contractor to determine the size of your heating and cooling equipment. Some contractors oversize the equipment “just to be sure.” In many cases, oversize equipment costs more than equipment of the right size.

Quiz your designer

Before you choose a designer or architect, ask the candidates a few questions.

What makes a house green? A designer who mentions things like “keeping the house small” and “keeping energy bills low” is on the right track. A designer whose first answer is “choosing green materials” may not be the one you want to hire.

What design elements contribute to energy savings? Good answers include “paying attention to airtightness” and “making sure that the walls and ceilings are well insulated.” You don’t want to hear “choosing a furnace or air conditioner with a high efficiency rating.”

When you talk plans, does your designer indicate the location of a home’s air barrier? An air barrier is a continuous layer whose purpose is to reduce the leakage between indoors and out. If the designer says “yes,” that’s a good sign. A designer who says “no” may be a good designer, but he or she will probably require some amount of hand-holding and education.

Quiz your builder, too

You want a builder who understands basic building-science principles; he or she should have an understanding of heat-flow mechanisms, water-vapor permeance, condensation, and the effects of air leakage. Ask your builder some questions.

Have you built a home with an airtightness goal included in the specifications?

How many homes have you built whose airtightness was tested with a blower door? What were the results? Results of 2.5 air changes per hour at 50 pascals (ACH50) or fewer aren’t bad, but 1.5 ACH50 are better.

What’s a good way to address thermal bridging through studs? Thermal bridging is the direct conduction of heat through building members, bypassing the insulation. Good answers include “building a doublestud wall” or “with exterior rigid foam.” A not-so-good answer would be “What’s thermal bridging?”

Red flags

If your designer or builder suggests any of the following features, consider the suggestion a red flag:

- Forced-air ductwork installed in an unconditioned, vented attic.

- Fiberglass batts to insulate the interior of a basement wall.

- Spray-foam insulation that doesn’t meet minimum code requirements. The faulty explanation for this approach is typically something like “Because R-20 spray foam performs better than R-38 fiberglass.”

- Recessed can lights in an insulated ceiling.

- Pull-down attic stairs in an insulated ceiling.

- Tongue-and-groove boards as the finish material on a cathedral ceiling insulated with fiberglass batts, unless drywall has been installed first.

- A powered attic ventilator (that is, a fan to keep your attic cool).

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Foam Gun

Nitrile Work Gloves

Staple Gun