A Practical Air-Sealing Sequence

If you aim to build a superinsulated airtight home and want to keep it affordable, your best bet is to use common materials and methods that don’t disrupt traditional work sequences very much.

Last year, my architecture firm’s founding partner, Bruce Coldham, developed a set of details to create an affordable, durable, and continuous air barrier for a house with a conventionally framed 2×6 wall and a truss roof.

Airtight wall sheathing

We opt to use the exterior face of the wall sheathing as the air barrier, using either Huber Zip sheathing and Zip tape or a handmade version: OSB with Grace’s WB Primer and Vycor tape at all joints, burnished or rolled to get the best adhesion.

This strategy keeps the air barrier out of the way of the electricians and plumbers who are called on to punch many holes in our walls. It also provides a durable, inspectable, and affordable solution to reducing air leaks. With a continuous layer (or two) of rigid polyiso over the OSB, we get warm sheathing and good overall wall R-values as well.

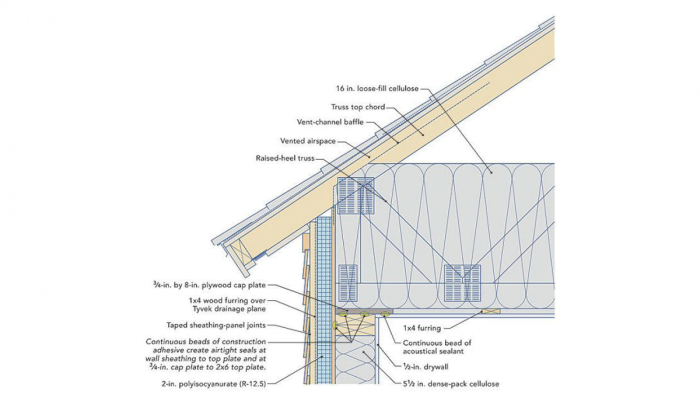

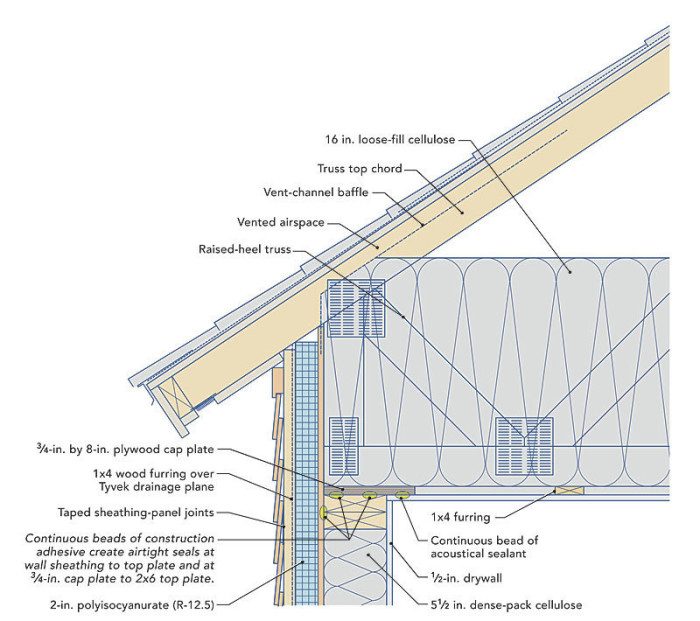

The wall-roof intersection

For reasons of construction economy, many clients want trussed roofs with traditional eaves and a ventilation channel. The immediate challenge in this design is figuring out how to connect the exterior sheathing air barrier on the walls to the interior drywall air barrier at the ceiling.

The solution is found in a simple plywood cap plate (3/4 in. by 8 in.) that is attached to the exterior walls. To achieve airtightness at this transition requires the use of construction adhesive in two locations: The wall sheathing has to be sealed with adhesive along the 2×6 top plate, and the plywood cap plate has to be sealed to the 2×6 top plate that it’s nailed to.

Doing it this way doesn’t interrupt the construction sequencing, and the materials needed to accomplish it are typically on site already.

Wall-to-roof transition

The exterior walls are capped with a plywood plate that is 3/4 in. thick and 8 in. wide. The plywood cap is the same thickness as the 1x4s used to strap the ceiling.

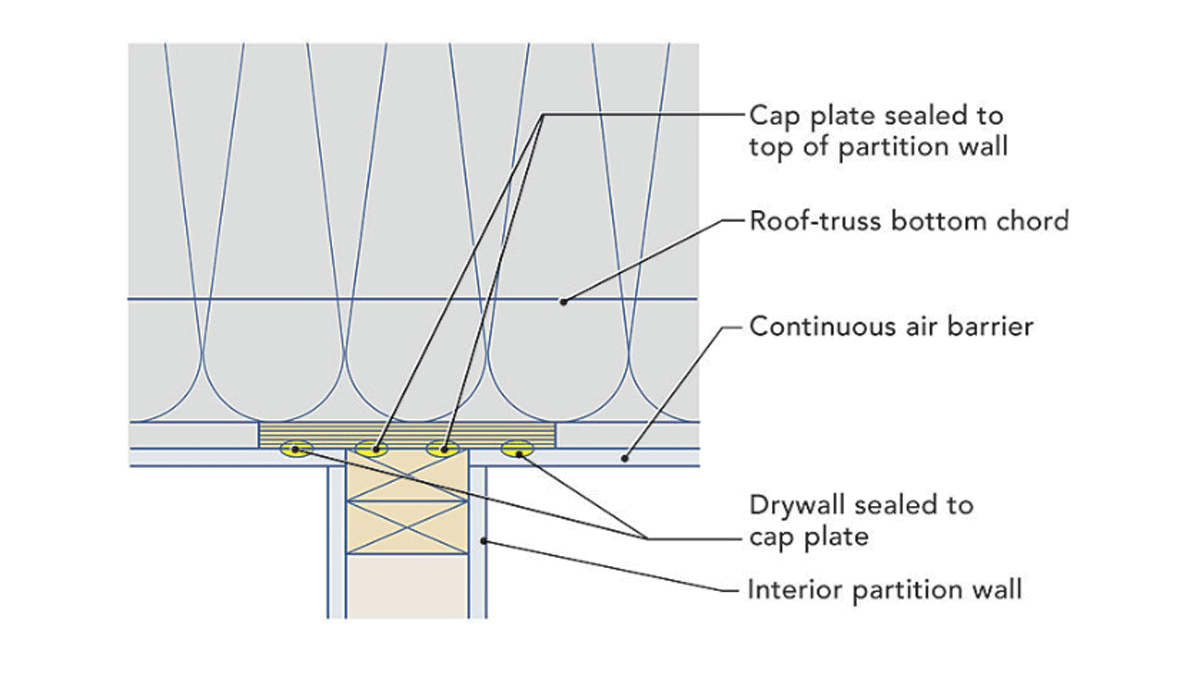

Detailing partitions

With an airtight drywall ceiling, the tops of partition walls threaten to interrupt the air barrier. We could handle this in two ways: either by having a continuous plane of drywall installed before the partitions are erected, or by adding another plywood cap plate atop each partition wall.

Adding a continuous layer of drywall demands mobilizing the drywall contractor twice. Adding cap plates helps to keep the normal construction sequence intact.

A bead or two of construction adhesive is used to seal the top plate of the partition wall to the wide plywood cap plate. A similar bead seals the cap plate to the drywall ceiling. The drywall is fastened to the plywood cap plate and to 1×4 furring strips in the same plane.

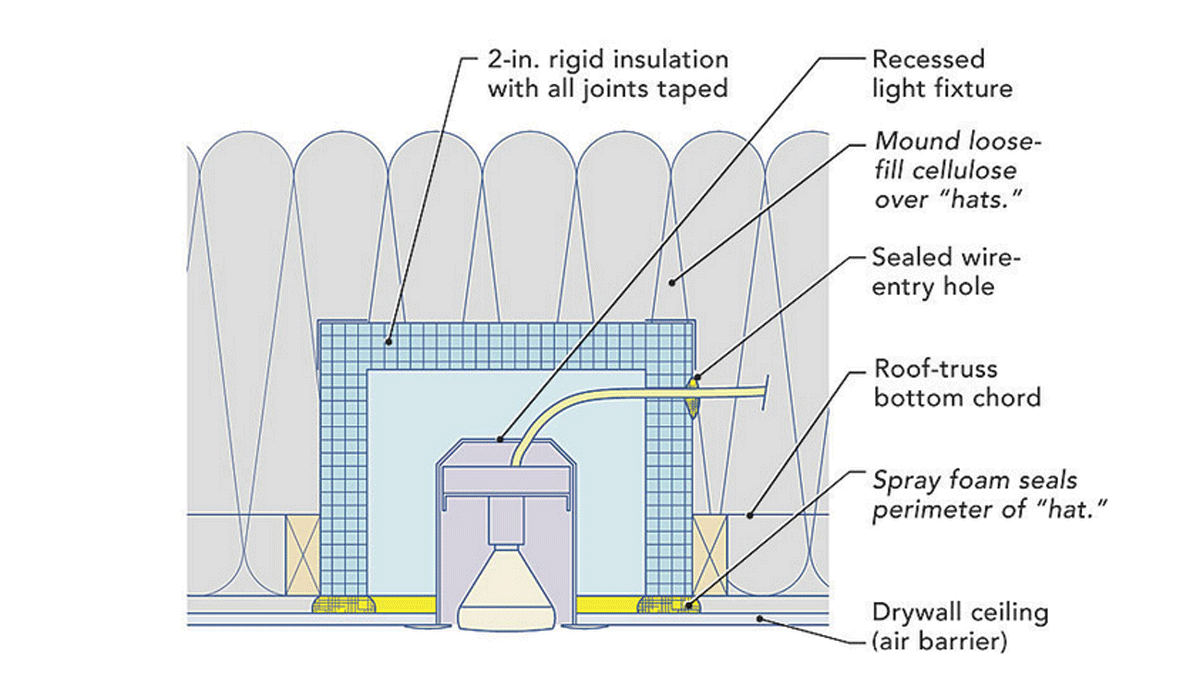

Finally, any ceiling penetrations, especially recessed can lights, need to be carefully sealed, which can be accomplished with an air-sealed “hat” made of rigid foam and canned spray foam and tape (see drawing and “Recessed Can Lights” in FHB #237).

To create an affordable superinsulated airtight home, it helps if the details are simple rather than disruptive. A little creative forethought and a clear plan will help builders get it done.

Airtight partitions

You can install continuous drywall on the ceiling before partition walls are framed, or use this detail to stick to a more traditional building sequence. The plywood caps installed above the partition top plates are wide enough to provide an overhanging lip on both sides of the partition to receive beads of sealant.

Don’t forget the can lights

Air leaks at recessed can lights often lead to winter ice dams. Even recessed cans that are rated IC and “airtight” are known to leak. To create a more airtight ceiling, construct rigid-foam boxes that are air-sealed with tape and canned spray foam. The boxes should be sealed to the drywall before loose-fill insulation is installed.

Applied eaves make an airtight hot roof work

2×4 eave rafter = 3-1⁄2 in. of rigid foam. If a house is framed without any roof overhangs, it’s easy to tape the seam between the wall sheathing and the roof sheathing. Once the sheathing is airtight, “applied eaves” are framed with 2x4s, which will be on the same plane as the 31⁄2 in. of rigid foam that is installed next.

We’ve employed the sheathing-based air-barrier solution regularly since testing it out with energy consultant Marc Rosenbaum at the College of the Atlantic’s Davis Student Village. There we achieved near Passive House airtightness with OSB, primer, and Vycor for our wall and roof assemblies.

We have long believed that aligning the weather, air, and thermal barriers is the most bulletproof way of making wood-framed structures in our climate. But this is more expensive to do on a roof than on a wall, because it either complicates the venting requirement or requires an unvented “hot” roof. The current code requirements for hot roofs—designed to avoid condensation on the inside of the sheathing—are more elaborate than earlier methods used in our area.

For a high-performance house with a hot roof, we often use 12-in. I-joist rafters filled with dense-pack cellulose. To comply with the code, this type of roof needs 3-1/2 in. of continuous rigid insulation above the primary roof sheathing in our climate zone.

If the roofs are framed without any overhangs, the wall sheathing can extend all the way up to the roof sheathing. Once the sheathing seams are taped, including the seam where the wall meets the roof, we sometimes install 2×4 outriggers to create an “applied eave” (see photo). The height of the 2×4 outriggers matches the thickness of the foam insulation.

Photo: courtesy of Coldham & Hartman Architects. Drawings: Steve Baczek, Architect.