What’s the Difference: Wooden Scaffold Plates

Stay away from construction-grade lumber and choose instead between solid-sawn planks and engineered LVL planks.

In 2013, scaffolding was no. 3 on OSHA’s list of most frequently cited violations, and for good reason. A 2009 survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that 54 workers died in falls from scaffolding. OSHA estimates that 4500 injuries could be prevented every year by following its regulations on scaffolding and by training all workers in safe practices. Having well-built, sturdy scaffolding won’t matter, however, if the board you’re standing on isn’t meant to support the load you’re putting on it.

Several options exist for wooden scaffold planks, but construction-grade lumber isn’t one of them. No matter how sturdy those extra 2x10s might appear, don’t be tempted to use them on scaffolding. Construction-grade boards are rated for their capacity to handle building loads, not the loads created by workers and their equipment.

If you work on scaffolding, be sure to inspect planks regularly for damage that could compromise their strength. Splits, sawkerfs, mold and mildew, insect damage, and delamination (in the case of LVLs) are examples of conditions that could render a plank unsafe to use. Many of these problems can be prevented with proper care, but if a plank’s condition makes you question its strength, discard it.

Solid-sawn planks

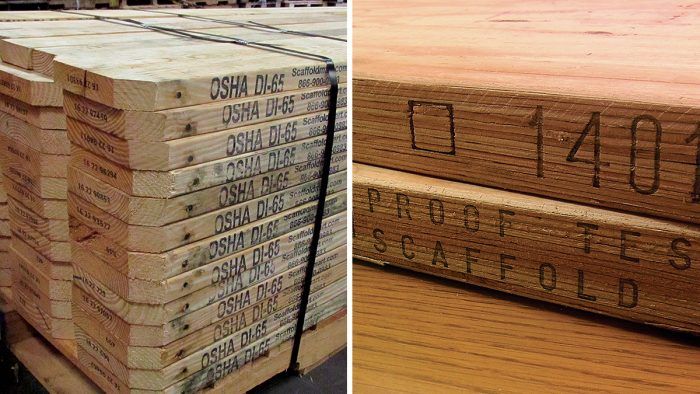

The most common wood used for solid-sawn scaffold planks is southern yellow pine, which the Southern Pine Inspection Bureau grades as DI-65 or, less commonly, DI-72. DI stands for “dense industrial”—in contrast to construction-grade boards, which are graded “structural” or “dense structural”—and the number represents a strength ratio in which the higher the number, the smaller the knots and the straighter the grain.

Planks also can be made from Douglas fir and similar species, and these have their own grading nomenclature. For example, the West Coast Lumber Inspection Bureau grades scaffold planks, in descending order of strength, as “dense premium,” “premium,” “dense structural,” and “select structural.” No matter the species, scaffold planks should be labeled as such and clearly distinguished from construction-grade boards. Though OSHA does not require it, scaffold-grade boards from reputable manufacturers also should carry a stamp that includes the grade, the moisture content (no more than 19%), the lumber-mill name and/or number, and the seal of an approved third-party inspection agency.

Manufacturers often take steps to extend the life of their planks: They seal the end grain against moisture, they insert rods through the ends of planks to prevent cupping and to keep them from splitting along their length, and they clip the corners. This last step helps to prevent splitting if a plank is dropped on a corner.

Solid-sawn planks are available in lengths from 8 ft. to 16 ft. The longer the span between supports, the less weight the board can safely handle. For example, to handle three workers (250 lb. each, including tools) who are spaced evenly apart, the maximum span is just 5 ft.

LVL planks

These engineered boards, made from thin layers of veneer held together with an exterior-grade adhesive, minimize cupping and the effect of imperfections such as knots. The result is a somewhat stronger board that, for example, can accommodate a three-worker load on a 6-ft. span. LVL planks are available in the same sizes as solid-sawn boards and at a slightly higher cost. Most companies seal the ends against moisture, and some offer boards with an abraded surface for better traction. They don’t insert rods in the ends, and they don’t clip the corners, however, because an LVL plank dropped on its corner is far less likely than a solid-sawn plank to develop a severe split.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Flashing Boot Repair

Roof Jacks

Fall Protection