Q:

Our crew is building a new two-story house. By the time the flooring installer came on site, there was a hump in the subfloor at a few of the doorways and cased openings. All of the doorways and openings in question have built-up LVL beams under them, but the rest of the floor structure is framed with 2x12s. Was it a bad idea to combine these different materials?

Chris K., via email, None

A:

My guess is that the humps in your floor have to do with the moisture content of the lumber you installed.

In the old days, floors were framed completely with dimensional lumber, and joists and beams likely came from the same stack of lumber sitting in the same spot at the lumberyard. That meant that both joists and beams would have a similar moisture content, so if they dried out and shrank after installation, they would shrink about the same amount, and the change would go relatively unnoticed. When you mix dimensional lumber with LVLs or other engineered lumber—which, by the way, is perfectly acceptable—you need to factor in the moisture content of the two different materials.

An engineered beam will likely come from the mill with a moisture content of between 4% and 6%, and will be coated with a protective wax to prevent moisture absorption. That, combined with the fact that LVLs are made from thin strips of lumber to promote stability, means that there will be very little change in the height or the length of the beam after it’s installed.

Dimensional lumber is very different. It may arrive at your job site with a moisture content anywhere from the point of fiber saturation (28% or more) down to a moisture content of 6% or so, which is a common point of equilibrium for interior woodwork.

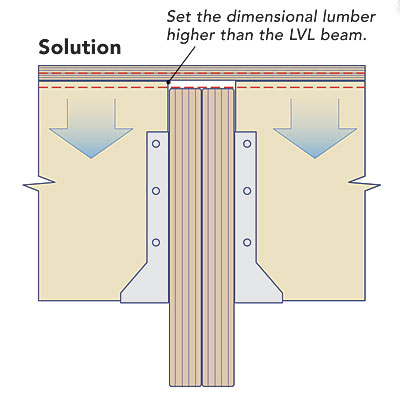

If the floor joists are set so that their top edges are flush with the top edge of the beam, then as the floor joists dry out and shrink, they will leave the LVLs proud of the joists (top drawing). My guess is that this is what happened on your job. It’s not uncommon, but it can be avoided.

By checking the moisture content of the lumber before it’s installed, framers can predict the amount of movement that will occur across the grain of dimensional lumber. It’s not an exact science, but a good rule of thumb is that if the moisture content of a board changes by 4%, the board will shrink across the grain by approximately 1% of its width.

For example, let’s say that I’m going to install 2×12 floor joists up against an 11-7/8-in. LVL beam. If the joists have a moisture content of 18% and will eventually dry to a moisture content of about 6%, I need to assume a differential of 12%. To figure out how much the joists will shrink, I divide that 12% differential by 4 and see that my 2x12s will shrink by 3%. Rounded for simplicity, the shrinkage of the joists will likely be 3/8 in.

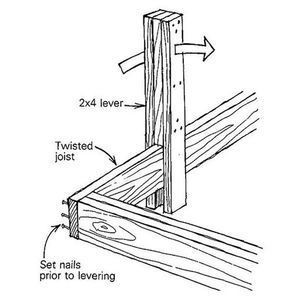

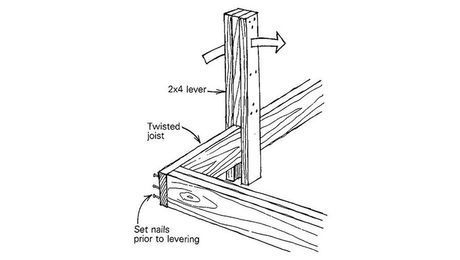

The solution? I set the joists 3/8 in. higher than the LVL beam. That way, I’ve left enough headroom for my worst-case scenario and eliminated the potential for the hump in the subfloor.

By the way, this rule of thumb is also useful in remodeling projects. Calculating movement helps when joining new lumber to old, well-dried lumber structures. It can prevent the common problem of the new construction falling away from the old and causing separation in floor and wall surfaces.

Photo and drawings: Dan Thornton

View Comments

With a bearing wall above the beam such as an interior roof point load often designed on hip roofs say, would not implement this and have the load directly on the joists and not bearing on the beam since the joist hangers are not rated for loads other than the floor. If the beam is in the middle of the floor I think this is fine. There's no one size fits all and if a floor is installed within a quarter plane that is good, planning for a calculated shrinkage is good but it's better to use the right materials in the first place that will behave similarly.