All About Washing Machines

The overall efficiency of machines are rated two ways: the modified energy factor (MEF) and the water factor (WF).

1

About 82% of homes in the United States have a clothes washer. Each of these appliances washes about 300 loads of laundry per year and consumes more energy than a residential dishwasher but less than a residential refrigerator. Although there are a few exceptions, most washing machines fall into one of two categories: top-loading (vertical-axis) models or front-loading (horizontal-axis) models.

Two types of washers

Front-loading machines cost more than top-loading machines, but they use less water and detergent. Since they’re free of a twisting agitator, they’re easier on clothes than top loaders. They also spin faster than top loaders, so they remove more water, shortening drying time. Because of these advantages, about half of the residential washers now sold are front-loading machines.

The average full-size, front-loading, Energy Star clothes washer uses around 15 gal. of water per load compared to about 23 gal. per load for a top-loading machine without an Energy Star label. In a report for the January/February 2012 issue of Home Energy magazine, two California researchers, David Korn and Lauren Mattison, measured the amount of energy and water used for washing and drying clothes in 115 California homes. They found that Energy Star washing machines use the same amount of electricity as their non–Energy Star counterparts: “They save energy by using less water to wash clothes and by removing more water at the end of the wash cycle, thereby allowing for shorter dryer cycles.”

Many writers suggest washing clothes in cold water to save energy. While it’s true that cold-water washing does save energy, Korn and Mattison explained that the savings aren’t as great as they used to be: “Efficient clothes washers use as little as 12 gallons of water per load. Hot water represents only a small part of this amount even for hot cycles.” The minimal savings are easy to understand when you consider that even when you choose the hot cycle, most washing machines still use cold or warm water for the rinse cycle.

Consider standby power

Unlike older washers, newer models of clothes washers have a measurable phantom load—in other words, they use electricity even when they appear to be off. According to Korn and Mattison’s measurements, this standby load averages 0.34kwh per week. Since a washing machine requires only 0.21kwh per load of laundry, homeowners who only wash one or two loads of laundry per week will find that a significant percentage of the electricity used by their washing machine (45% to 62%) is devoted to standby power.

Shopping for a new washer

If you are an energy-conscious homeowner shopping for a new washing machine, you can assume that your new washer will do a good job of cleaning your clothes. An August 2012 Consumer Reports article on clothes washers reported that performance problems with the first generation of energy-saving washers have been solved. The authors noted that “good cleaning, high efficiency, and large capacities are common features of the newest washers.”

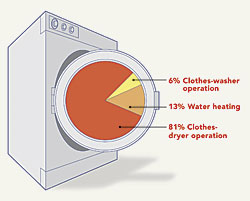

With washing performance less of a concern, you’ll want to pay greater attention to the federal government’s metrics for rating the efficiency of washing machines. The most recognizable is the yellow Energy Guide label. Unfortunately, the yellow label only includes washer energy and water-heater energy, not the energy ultimately consumed by a clothes dryer, which is contingent on the efficacy of the washer’s spin cycle. A better snapshot of a washer’s efficiency comes from the federal government’s other two efficiency criteria: the modified energy factor (MEF) and the water factor (WF).

The MEF is calculated by dividing the clothes washer’s capacity (in cubic feet) by the power (in kilowatt hours) used for one load of laundry by the clothes washer and the clothes dryer; this calculation includes the energy required to heat water for one laundry load.

Since the MEF calculation takes into account the energy needed to dry clothes, it rewards washers that have a high-speed spin cycle. The higher the MEF, the more efficient the washing machine. At this time, federal regulations require that residential clothes washers have a minimum MEF of 1.26. The minimum MEF for Energy Star machines is 2.0.

The WF is calculated by dividing the amount of water used for one load of laundry (in gallons) by the clothes washer’s capacity (in cubic feet). The lower the WF, the more efficient the machine. At this time, federal regulations require that residential washing machines have a maximum WF of 9.5. The maximum WF for an Energy Star machine is 6.0. The bottom line is that you want a model with a high MEF and a low WF.

Positive trends

Over the last two or three decades, clothes washers have gotten more efficient; somewhat surprisingly, they also have gotten cheaper. According to the advocacy organization Appliance Standards Awareness Project, “Between 1987 and 2010, real prices decreased by about 45% while average energy use decreased by 75%.” However, these newer machines take longer to wash clothes than older models. In 2005, the average old-fashioned top-loading machine required 50 minutes per load. In 2012, the newer frontloaders averaged 79 minutes per load.

Consult these resources when choosing a high-efficiency washing machine

• Energy Star (energystar.gov) maintains a list of clothes washers that meet the “most efficient” designation, which have an MEF of 3.2 or more and a WF of 3.0 or less.

• The Consortium for Energy Efficiency (cee1.org) publishes a list of qualifying energy-efficient clothes washers.

• Top Ten USA (toptenusa.org) simplifies the washer-buying process with a useful list of the top ten most-efficient washing machines.

Drawing: Dan Thornton