The Passive House Build: Getting the Mechanicals Right

A carefully designed mechanical system rounds out this house’s heating and cooling load.

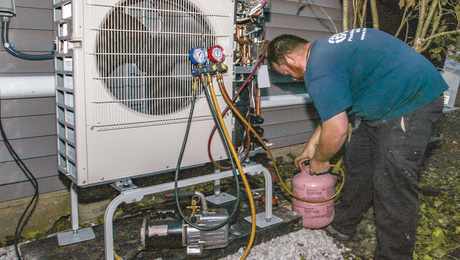

Synopsis: Although a Passive House is designed and built to be heated primarily by the energy from sunlight, there is almost always a secondary source of heating. Architect Steve Baczek explains the choices that were made in this energy-efficient home in Cape Cod—from the reason he chose a ductless minisplit heat pump, to his experimental plan of using the house’s energy-recovery ventilator (ERV) not only to bring in fresh air but to circulate the conditioned air from the single minisplit. Photo: David Fell, courtesy of Steve Baczek

Although many superinsulated houses are designed and built to be heated primarily by the energy from sunlight, there is almost always a secondary source of heating. The house shown here, which was covered in a recent series of five articles and videos, is no exception. It receives 50% of its total required heating from the sun — with another 25% from electronics, appliances, and occupants — but the remaining 25% must be handled by mechanicals. This heating requirement — about 6000 Btu — leads to some challenges.

The first is that such a small heating load makes it difficult to find right-size equipment. But even at twice the necessary output, the 12,000-Btu minisplit we ended up choosing is still more reasonable than the smallest furnace, which typically isn’t designed to produce anything lower than 50,000 Btu.

The second problem is distribution of the conditioned air. Unlike a typical furnace and attendant ductwork, a ductless minisplit delivers the heating and cooling in bulk, and all in one location. Although the open floor plan of the house is designed to help distribution, there are still bedrooms and bathrooms that require some level of privacy and are therefore more difficult to keep comfortable. In other Passive House designs, I have solved this issue by spreading the work across multiple minisplits located in different areas of the house. In this home, we wanted to deliver the needed loads with a single minisplit, so we relied on the ERV (energy-recovery ventilator) to handle our distribution.

An essential element in this tight house, the ERV operates all day every day, taking stale air from the kitchen and the bathrooms and exchanging it with fresh outdoor air, which is then supplied to the bedrooms. The conditioned air from the minisplit is piggybacking on the circulation already provided by the ERV. This approach is working well, and the house stays at a comfortable 65°F to 70°F.

Wanting to have a backup plan — due to concerns that a single minisplit might have trouble keeping up with the summer dehumidification — we plumbed and powered a second minisplit rough-in should it be necessary to add a second unit.

We also outfitted the three bathrooms with small wall-mounted electric-resistance heaters. Although they were not necessary from a whole-house-heating standpoint, a bit of extra comfort is appreciated in bathrooms, especially on cold New England mornings.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: