When I was eight years old and saw a crew framing a house, I thought that had to be the coolest job in the world. I still think so. There is nothing better than waiting for the sunrise, breaking the bands on a new lumber package, and imagining what we’ll accomplish by the end of the day.

My passion for the craft made me the guy who always wanted my clients to feel they had received something wonderful. Over time, I came to appreciate the efficiency of a skilled team that could deliver a highquality product quickly at a fair price.

Over the decades, I have moved between residential and commercial projects. My first commercial job—as a concrete laborer on a three-story library remodel—was quite a shock. I had never been on a job site where so much happened at once. While the pace of individuals was deliberate and measured, the overall tempo of the job was stunning. Using a crane to lower a skid-steer loader through a hole in the roof to expedite demolition introduced me to an aspect of problem-solving that was beyond my experience; so was the realization that structural steel could be set so accurately that an oak reception desk could fit with no more than 3/16 in. to spare.

Going back to building houses was initially a relief, but then a troublesome pattern emerged. When progress slowed or stopped—if, perhaps, the foundation was off, a sub didn’t show up, or the roof couldn’t be built the way it was drawn—I would find myself thinking, “This wouldn’t happen on a commercial site.”

Not all commercial jobs are well run, but when properly applied, the processes used in building our office buildings, retail centers, and transportation hubs can make great achievements possible. They can also make ordinary achievements far more satisfying for all involved. I began to think, “What could the people who design and build homes learn from the people who design and build everything else?”

A balancing act

Large commercial projects are defined by demanding schedules, complex scopes of work, narrow profit margins, scant room for error, and tremendous value at risk. They involve working with architects and owners’ reps who are familiar with the construction process and have realistic expectations. In that context, it is routine to deliver a quality product on time, on budget, and suitable for its intended purpose.

By comparison, custom residential projects tend to have smaller budgets, drawings that are not as detailed or well-developed, fewer specifications, a less definite scope, and a more flexible schedule. Residential clients are generally less experienced in the construction process; this is the biggest purchase they will ever make, and for most, a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Yet there are similarities. Both types have, in one form or another, an owner, a designer, and a builder. The owner wants the lowest possible price, the designer wants the best possible quality, and the builder wants the job done as quickly as possible. If the builder (or the owner) is also the designer, this dynamic tension remains, still influencing the outcome. Those who have designed their own home, bought the materials, and nailed it together themselves understand these trade-offs acutely.

Enter the triangle

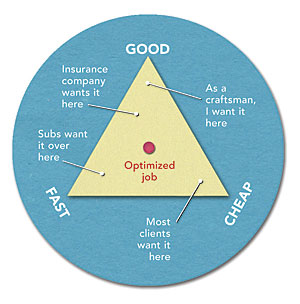

If you’re in the building business, you’ve probably seen the illustration showing a triangle with its corners labeled good, fast, and cheap, with the instruction “Pick two.” It’s meant as a joke, but it can also be used as a tool in comparing the commercial building experience to the residential building experience.

In viewing the choices presented by the graphic in a more serious light, asking a customer to pick two is a crude simplification. What we’re really negotiating is where we can position the job inside the triangle. Taking everyone’s interest into account, the optimized job is dead center, but like so many mediations, this also means everyone gets a little less than they’re angling for. The “optimized” job is positioned at the greatest possible distance from everyone’s goals.

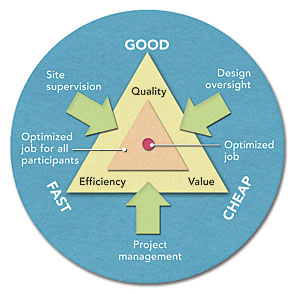

Commercial construction has taught me that we can shrink the size of the triangle. Instead of moving the project toward one participant’s goal and away from the others, we place the participants at the center and move the goals closer to them.

There are two ways to make this happen. First, apply pressure to the process in three areas often overlooked in custom residential projects: design, project management, and site supervision. Second, redefine those troublesome descriptors of good, fast, and cheap to describe the virtues we are really chasing: quality, efficiency, and value.

Through collaboration, we maximize these outcomes. For example, within my core group of commercial contractors, subcontractors, and vendors, we have established relationships of mutual respect and purpose, oriented toward shared goals. I don’t ask them to lower their price. Rather, I ask them to help me lower the overall cost of the job, and involve them in this process as early as possible. As a result, they bring ideas that I have not thought of. Likewise, I don’t ask architects to value-engineer anything; it’s rarely a value, and the engineers often do not approve the result. And I don’t ask owners to pay more than they can afford. It’s all part of shrinking the triangle.

Dialing in design

“I can fix that” are the four most expensive words in construction, especially if the result of a mistake bumps a sub off the schedule. Thorough and technically competent design, coordinated drawings, fully developed details, clear specifications, and third-party constructability review all translate directly into quality, efficiency, and value—as well as profitability.

The builder of a school or a medical facility wouldn’t break ground without having worked out exactly how the civil, structural, HVAC, plumbing, electrical, roofing, and finish details come together, but that hasn’t been my experience in residential design. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been on a residential job that came to a full stop when we encountered a design bust. The only thing worse than having a crew standing around while the boss figures out how to do something is having the boss standing around while the crew disassembles something they just built.

The commercial process is front-loaded with regard to design, with a clear understanding that the more we can figure out ahead of time—when the project is still just a few people discussing a set of drawings— the less we have to correct on-site when interrupted progress can cost quite a bit more. This prebuild design work creates inward pressure on the leg of the triangle that brings us closer to the goals that we now recognize as quality and value.

Managing for efficiency and value

With design parameters clearly defined and understood by all involved, skillful project management is the next factor necessary for a project to end successfully. This falls primarily in the planning and scheduling area.

I haven’t been on many residential job sites that take planning and scheduling seriously enough, particularly regarding subcontractors. The first time I suggested a preconstruction meeting to a residential builder, he looked at me like I had asked the question in a dead language. It’s a step often disregarded by residential builders, but it shouldn’t be. It’s amazing how many good ideas you get when each party talks about how we can all do a better job together. Making these meetings part of doing business enables builders to eliminate scope gap, control the schedule to make steady progress without workers getting in each other’s way, and provide the clarity and coordination needed for everyone to remain profitable at a high level of quality.

In addition to clear communication with subs, professional project-management practices such as proper accounting, timely payment, and ambitious-but-realistic scheduling also help keep everyone working productively and effectively. This effort pays compound interest and is a reliable and replicable way to deliver the greatest value in the most efficient manner.

Supervision on site

Every orchestra needs a conductor, and every building project needs a site superintendent. A good site super makes sure the conditions are right so that everyone can do his or her best work.

Every residential job I’ve ever been on was supervised more or less by a lead carpenter. This individual might or might not understand (or care) what circumstances will maximize productivity and efficiency for the sub trades. Effective site supervision brings everyone closer to the goals of quality and efficiency, because keeping everyone working in a productive, coordinated manner translates directly into a good job completed on time.

Using the commercial model, a good site super is committed to the success of every person on the job in the context of delivering a successful project. When a job has good site management, it’s amazing how many days you don’t lose to bad weather; when a job site is kept clean and organized, it’s amazing how much more productive workers can be. Going out of your way to form the conditions for everyone’s success is an investment of intellectual capital that pays big dividends in profitability, goodwill, and quality.

The craft of business

Many residential builders spend 10, 20, or 30 years in a rigorous pursuit of their trade. The beautiful result their clients can see doesn’t come out of the blue; it comes from knowledge, skill, experience, and the culmination of a lot of focused hard work.

The business component of fine home building is an essential precondition of this process. It starts before the batter boards go up, and it continues until after the punch list is completed. It provides the context that allows everything else—including craftsmanship— to happen.

Because the risk is so great and the margins are so small, commercial builders simply cannot afford to ignore this. But small residential builders shouldn’t either. By applying the same principles as commercial builders, residential builders not only can become more productive and profitable, but they also can use the resulting surplus creatively to everyone’s benefit.

Drawings by Dan Thornton