How it Works: Ground-Source Heat Pumps

In heating mode, the pump uses the ground as a heat source; in cooling mode, it uses the ground as a heat sink.

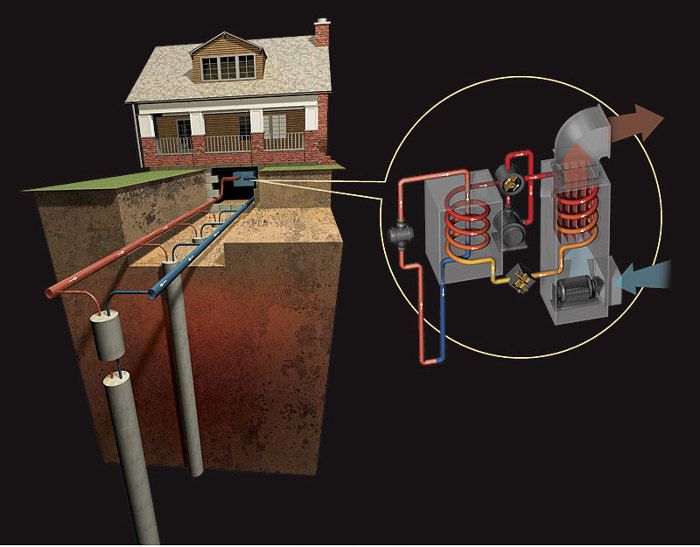

Synopsis: A ground-source heat pump uses the relatively stable temperature of the earth below 20 ft. to keep a house cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It works by cycling a refrigerant back and forth between the ground and the house. In heating mode, the pump uses the ground as a heat source; in cooling mode, it uses the ground as a heat sink.

Left to its natural devices, heat energy flows from areas of high temperature to areas of low temperature. A heat pump reverses this natural process, absorbing heat from a relatively cool environment and moving it to a warmer area.

A window air conditioner is a common example of a heat pump. The interior of a room is not cooled by pumping it full of cold air; rather, it’s cooled by extracting heat from the room and dumping it outside. A heat pump can also be used to warm a room by reversing the process—that is, pulling heat energy from the exterior air and distributing it inside.

The flaw of air-source heat pumps (ASHPs), the most common type, is that their efficiency decreases with increased temperature extremes. The more frigid the air outside your house, for example, the harder the ASHP has to work to extract usable heat energy. That’s why many homes are relying on ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) for air-conditioning and heating at a higher level of efficiency.

Instead of air, a GSHP uses the relatively stable temperature of the earth as either a heat source or a heat sink depending on whether the system is in cooling or heating mode. Here’s how it works.

Heating and cooling, courtesy of the earth

Although the temperature of the upper 6 ft. or so of soil varies based on the air temperature, if you dig to at least 20 ft., the ground temperature is roughly equal to the annual ambient temperature at that latitude. Depending on whether the house’s heat-pump system is in cooling mode or heating mode, the soil is used either as a heat sink or a heat source.

For diagrams and more details on the refrigeration cycle of ground-source heat pumps, click the View PDF button below.

View Comments

There are several mistakes or misstatements in this article. The refrigerant is not pumped underground; it stays in the heat pump itself inside your house. Rather, a water-alcohol or water-glycol solution flows through the pipe, getting heated or cooled by the Earth (which is capitalized if you mean our planet, rather than dirt). The refrigerant is then either cooled or warmed by the solution instead of using air, as in an air-source heat pump.

Technically, a heat pump can be reversed, so a window air conditioner is not an example of a heat pump in this context. Yes, it pumps heat, but only in one direction.

Depending on the type of ground loop, the heat is not necessarily exchanged with the soil. Some ground loops go deep into the bedrock, and some are submerged in a pond or lake. Shallow ones, which extend hundreds of feet sideways in one's yard, do exchange their heat with the soil.

What is a ground source heat pump?

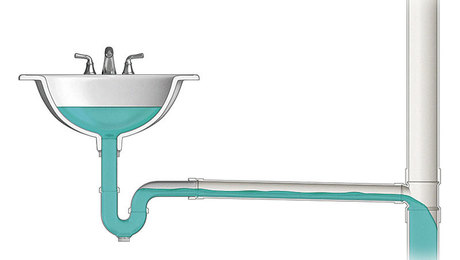

Ground source heat pump systems are made up of a ground loop (a network of water pipes buried underground) and a heat pump at ground level. You'll need plenty of space for the system to be installed - generally a garden that's accessible for digging machinery. How big the ground loop needs to be depends on how big your home is and how much heat you need.

How they work.

A mixture of water and anti-freeze is pumped around the ground loop and absorbs the naturally occurring heat stored in the ground. The water mixture is compressed and goes through a heat exchanger, which extracts the heat and transfers it to the heat pump. The heat is then transferred to your home heating system. A ground source heat pump can increase the temperature from the ground to around 50°C, although the hotter you heat your water, the more electricity you'll use. You can then use this heat in a radiator, for hot water, or in an underfloor heating system. Whether you'll need an additional back-up heating system will depend on your property.