How it Works: Wood Rot

No wood is completely immune to rot, so it's important to know how it works.

Synopsis: No wood is completely immune to rot, so it’s important to know how it works. Wood rot is caused by decay fungi that grow when the following conditions are present: temperatures between 40 and 105 degrees Fahrenheit, a wood moisture content 30% or greater, and sufficient food. There are two types of rot, brown rot and white rot, each of which is caused by a different fungus and displays different characteristics.

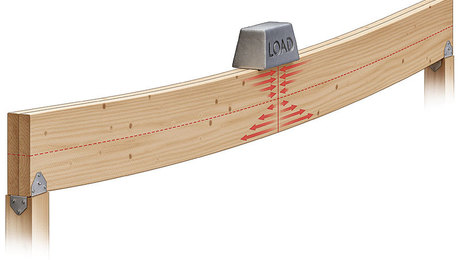

Despite what many people believe, wood doesn’t decay simply because it’s wet. This popular assumption is understandable, though, because it will never decay without water, no matter the implications of the misnomer dry rot. In fact, the slow process of wood decay, known as rotting, is caused by fungi. Much more than a cosmetic nuisance, decay fungi actually break down the cellular structure of wood.

Decay fungi have simple requirements for growth: temperatures between 40°F and 105°F (between 75°F and 90°F is optimal), a wood moisture content above the point of fiber saturation (roughly 30%), and ample food. Controlling the spores isn’t possible (they are everywhere), and eliminating oxygen would be unrealistic, but some conditions for growth can be altered effectively—for instance, chemical treatment can make the food source harder to access. Controlling moisture is also effective, although it only causes the fungi to go dormant and wait for favorable conditions to be restored.

Certain species have heartwood that is naturally resistant to attack from decay fungi, but no wood is completely immune to rot. Here’s how it works.

ZONES OF RISK

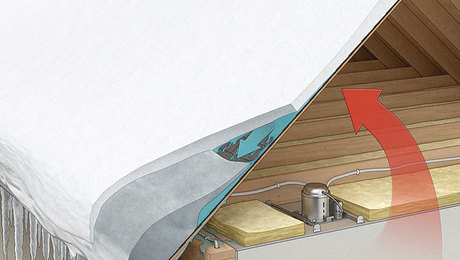

Although wood may be exposed to occasional spikes in moisture content from humidity or precipitation, it can easily dry to a moisture content of less than 20%, which is the threshold for decay fungi to reproduce. Aim for a moisture content of 6% to 8% for wood in indoor environments such as basements and crawlspaces, and 15% to 18% for outdoor locations.

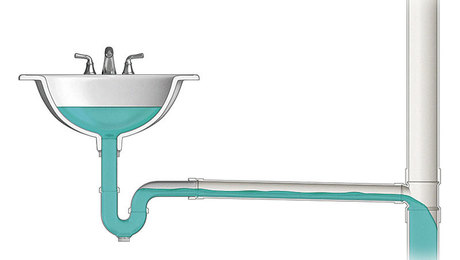

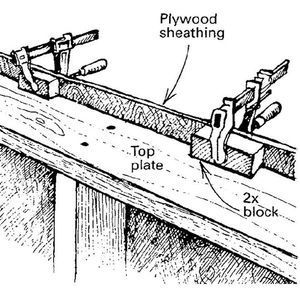

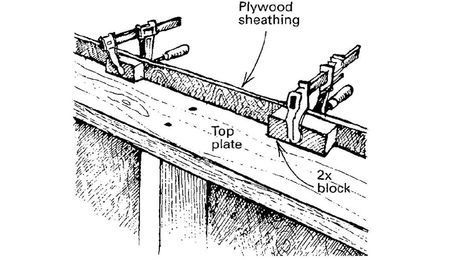

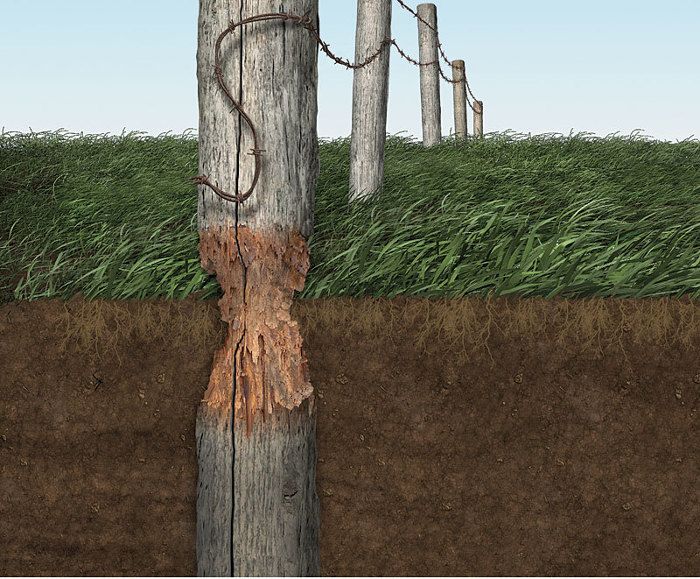

Decay fungi are most likely to thrive in situations where wood encounters elevated moisture levels, limited drying potential, and ample oxygen (cells consisting of at least 20% air volume). This danger zone commonly occurs where wooden posts meet the ground, where deck posts or sills rest on concrete, or where water is allowed to wick into exposed end grain— for example, the joint between window casing and the sill.

Wood that is buried below ground is less susceptible to rot than wood at grade level and will not rot when fully submerged in water, as oxygen is not present in fully saturated cells.

THE LIFE CYCLE OF DECAY FUNGI

Lightweight fungi spores floating in air land on the surface of wood. If conditions are right, the walls of the spores burst. Small tubes called hyphae branch out, consume free sugars, and then begin to secrete enzymes onto the surface of the wood, breaking it down to make more sugar.

As the hyphae spread and multiply, they form a whitish mat called mycelium, which absorbs the nutrients from the wood cells being broken down.

When a fungus has been growing for an extended amount of time, fruiting bodies start to form on the surface of the wood.

Fruiting bodies form millions of fresh spores that are then carried by the air to other surfaces, allowing the cycle to repeat.

For diagrams and details on the two different types of rot, click the View PDF button below.