California, my home state and fruit basket to the nation, is a harbinger of our country’s relationship with water, and it stands at the precipice of a profound resource deficit. Spring snowpack, the state’s main reservoir, has now reached a 500-year low, according to the research journal Nature Climate Change. If California doesn’t get record amounts of snow this winter, 39 million people will face an unmitigated climate disaster unless they adopt a wiser approach to water use.

We’re a nation of specialists, but most of our solutions sweep the negative impacts of those solutions out of one specialty and into someone else’s. To illustrate, the easiest way for a coastal area to get more water is to waste energy through the process of desalination. This is the most climate-damaging source of water, generating almost a gallon of CO2 per gallon of water. Pumping the salt out of ocean water near San Francisco uses as much energy as pumping freshwater from Canada, and the cheapest way to generate that energy is to burn coal. This in turn makes the climate hotter and more erratic, requiring more desalination. That destructive feedback loop is worse even than burning the furniture to stay warm; it’s more like burning the siding.

Drought calls attention to the fat in the system, forces people to manage water, and drives better policy. California just moved to regulate groundwater, the last state in the West to do so. Dramatically higher water costs incentivize more-efficient behaviors and more-efficient housing. It’s time for a fundamental shift in how we as a nation design our homes with respect to water—and kitchens and baths are two areas in the average home that consume the most. Designing these spaces as part of a house-as-ecosystem approach has small-scale and large-scale benefits. The more we change our systems and way of life now, the better the prospects will be for future generations.

Optimal integrated design

Context is king for ecological design. Building codes can’t possibly account for the factors that are unique to every home. A list of factors affecting a specific building site begins with the water supply. Other factors include the site’s topography, microclimate, site-available water from rain or stormwater runoff, soil, and potential for food production.

Every site requires water from either a metered source or the site itself. Green building is too often defined by the addition of green elements to a fundamentally conventional house that uses metered water as its only water source. True green building should be aligned with a house-as-ecosystem effort to lower water needs and to harvest site-available water, which requires deeper and more meaningful communication between architects who design homes and the tradespeople who construct them. The result of this communication is what I call optimal integrated design.

Into action

How might optimal integrated design play out in kitchens and baths, where the flow of water through houses is concentrated? The function of efficient kitchens and baths is generally the same in all homes, but how can water-conscious solutions influence the design of the plumbing and the way that a home interacts with its environment? Consider the practice of utilizing gray water for irrigation. Gray-water systems tune fixture flow rates, water-use habits, plant selection and location, and water-harvesting systems for a home’s particular soil and climate. Optimizing a home for gray water demands and rewards systems thinking.

Just as passive-solar heating can be a fundamental driver for the location and orientation of a house, graywater use can be a fundamental driver for the location and height of a home’s kitchen and bath above irrigated areas. Designed together, the plantings that define outdoor living spaces can be nurtured by the flow of nutrients and water from the home through short gravity-flow runs of pipe. In turn, these plantings can improve the climate inside the house. In California, a walnut tree on the south lets in winter sun and provides summer shade, as does a full-size citrus tree to the west. These changes benefit the homeowner through lower water, cooling, heating, and food bills. Gray water is one small but significant step toward dealing with the environmental crises we face.

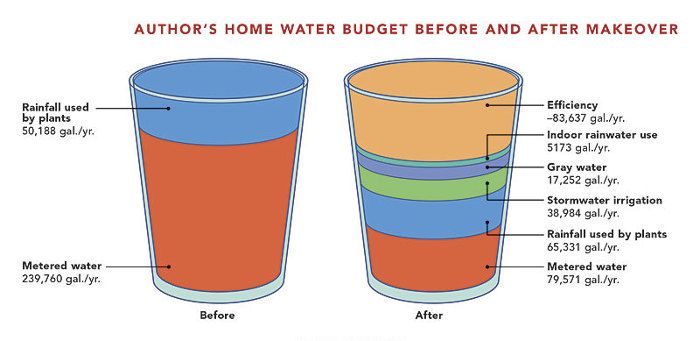

If the prospect of retrofitting your existing house for gray-water use seems overwhelming, don’t despair; there are much simpler actions you can take. For example, turn down the shutoff valves for the bathroom sinks to allow for the minimum water needed—more like 0.4 gal. per minute (gpm) than 1.5 gpm. There’s a few thousand gallons a year saved. Now turn off the hot water to your washer. You just lowered the carbon footprint of your water usage by a quarter. That’s progress, in minutes, with zero investment. (See “Take action,” right, for more ideas.) Each conservation measure we take is also a step away from a culture that venerates waste and a step toward a culture of stewardship. Get the scope, sequence, and numbers right for a water makeover, and you can really move the water-budget bottom line.

Remote water meter

Shows real-time and historical indoor and outdoor use separately

Solar hot water

A desirable feature for every house with a roof exposed to the sun

Right-size water heater

Occasionally running out of hot water is a signal, not a problem

Smart landscaping

Replace your lawn with plants that don’t need water or that give fruit, in mulch basins watered from your downspouts

Eco-luxury bathing chamber

A tight, insulated shower enclosure saves half the water and energy of a conventional stall while adding comfort and reducing condensation in the house

Drawings: Dan Thornton