Welcome to the Agrihood

Farming is central to a new breed of planned community

At the corner of New Urbanism and the local-food movement, a new type of neighborhood is rising: a tight-knit community built around an organic farm. With dozens of these communities filling up fast and hundreds more in the planning stages, “agrihoods” are one of the success stories of the postcrash housing market.

An agrihood is a planned development combining clustered houses and broad natural landscapes with farm-to-table living. It includes markets, community-supported agriculture (CSA) pickup points, community kitchens, and classroom areas, as well as miles of walking trails—all places for people to meet naturally and share experiences.

Developers are catching on as farm-based communities generate headlines, which drive brisk sales and a 10% to 25% premium in home prices. Developers also like how the clustered housing and amenities can mean millions of dollars less for streets and sewer lines.

Younger homebuyers, more interested in healthy food and hands-on living than golf courses and suburban sprawl, are drawn to the walkability and sense of community in these developments. Baby boomers, feeling nostalgic for simple pleasures that were common not so long ago, are flooding in also.

“I can’t imagine living anywhere else,” says Katie Critchley, who lives with three generations of her extended family in three homes at Agritopia, a 160-acre development in the Phoenix metro area.“Most people who live here want to know each other and support one another. The accessibility of the farm and services makes it a convenient way to live, so we have more time to focus on our relationships.”

Developments that preserve natural areas have been around since the 1960s. “Open space is cheaper than golf courses,” says Ed McMahon of the Urban Living Institute, a Washington, D.C.–based thought leader on housing and land use. “The initial idea was to use the marketplace as a tool for conservation.”

While early agrihoods were built around existing farms, the first of the current crop was Prairie Crossing, a community that broke ground in 1994 on 668 rural acres near Chicago.

“The developers’ belief was that an ecologically sustainable way of producing food should be a part of any community,” says Michael Sands, who helped to set up Liberty Prairie Foundation, the non-profit that owns the farmland at Prairie Crossing, runs a host of educational programs, and works to protect the farm’s future. “They wanted residents to have the opportunity to buy fresh food and see what growing looks like.”

Nathan Aaberg moved into Prairie Crossing in 2004. His sons attended its elementary school, which has an environmental curriculum and serves farm-to-table lunches, and the older son worked on one of the farms. “We knew that we could get more square footage for the money in other places, but Prairie Crossing had everything else we wanted our two boys to experience as they grew up,” he says.

All signs point to a trend. Agritopia, Prairie Crossing, and other agrihoods give frequent tours to developers and serve as models for communities such as Willowsford, Va., a 2100-home development that sold its first unit in 2011. McMahon says that the Urban Living Institute gets a call about a new agrihood “every other day.”

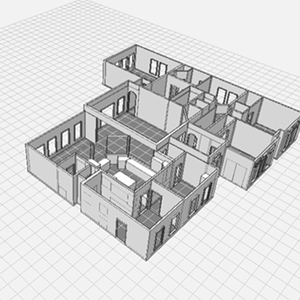

These new farm-based communities bring the same thoughtfulness to the houses themselves. At Agritopia, for example, the developer chose variety over similarity, mixing several classic bungalow and cottage styles. The porches face streets and neighbors, not garages and walls, and the homes have sprinklers so that the fire department would approve the narrow streets, which reduce driving speeds and encourage walking and visiting over driving and isolation.

Today, Prairie Crossing boasts a profitable 50-acre farm that sells produce to residents and members of the surrounding community and that serves as an incubator for new farmers. But success required patience and determination.

While infrastructure savings and free marketing are things that developers understand, farming isn’t. And the farm has to be in place early to generate the buzz that attracts homebuyers. Even at Agritopia, where the developers were a farming family, it took more than 10 years for the farming operation to turn a profit. That’s why most farms in agrihoods are subsidized by developers and homeowners. This can be risky; developers may walk away when the last home is sold, and the priorities of homeowners associations tend to change over time.

The challenges of incorporating agriculture into a housing development begin in the planning stages. A farm requires more capital than many developers realize—land, buildings, equipment, irrigation—and maintaining proper soil conditions adds another layer of complexity to its success. “It’s easier to build buildings than farms,” says Joe Johnston, a member of the family behind Agritopia.

Next, for a development-based farm to support retail sales via CSAs and farm stands as well as offer wholesale products to restaurants—two of the main routes to profitability—the farmers can’t merely grow one or two cash crops and then sell to a broker. The farm at Agritopia grows 300 different fruits, vegetables, and herbs. That means the developer needs to find a special farmer, one who is not only flexible but also entrepreneurial, deeply committed to the mission, and able to act as the face of the farm to present and future residents. Agritopia went through four farm managers before finding the right couple.

The managements at Prairie Crossing and Agritopia recommend creating a nonprofit that owns and leases the farmland and that ensures the future of the farm and its programs. They also believe that it’s critical for the farmers to own and operate their own businesses, which creates a strong incentive to watch the bottom line. Others in the field, such as Quint Redmond of Agriburbia, a farm design and consulting firm, back an outside-management approach, similar to the model for golf courses and swimming pools. “Your kids still get to be lifeguards,” he says, “and CSA is like buying a membership at the pool.”

Redmond is working with 30 developers on plans for new agrihoods worldwide, including a 1000-acre wellness community in Shanghai and a “steward” model in Colorado, where prospective farmers will buy a house lot that includes a farm tract where they will grow crops for value-added products, such as mint for organic toothpaste or barley and hops for craft beer. In fact, “value-added” is the talk at many agrihoods, in the form of artisanal foods and ready-made meals, which have bigger markets and margins than raw veggies.

Today, even the biggest farms in agrihoods supply only a small fraction of the food their residents eat. “This is just the state of the evolution toward local food,” Redmond acknowledges. “We are creating a multifunctional landscape,” says Mike Snow, the lead farmer at Willowsford in Virginia, “and we are only at the beginning.”

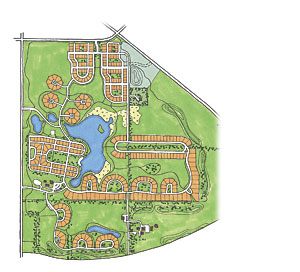

Prairie Crossing, Grayslake, Ill.

Part of the Liberty Prairie Reserve—3200 acres of publicly and privately held land that includes nature preserves, forest preserves, farms, and trails—Prairie Crossing was one of the first farm-based developments and has served as the prototype for many others.

Started in 1994 on 677 acres near the junction of rail lines to downtown Chicago and O’Hare airport, Prairie Crossing gathers 359 homes, 36 condos, a charter school, a fitness center, a horse stable, and a historic barn that serves as a community center on less than 40% of its land. The remaining land is preserved for an organic farm, a lake used for both recreation and storm-water management, and 10 miles of walking trails through native landscape.

The houses are spread out along the open spaces. In addition to making the lots seem larger, this “makes it easy to walk out the door and connect to the regional trail system,” explains Sunny Sonnenschein, who has lived at Prairie Crossing with her family from the community’s beginning. “We also love knowing that the Prairie Crossing Farm is changing the way people think about land use and what is possible in a suburban county in the 21st century.”

Agritopia, Gilbert, Ariz.

Agritopia is the result of a farm family’s endeavor to forge a new model of urban agriculture as the greater Phoenix metroplex closed in around them. It includes a 16-acre organic farm and 600 homes on its 160 acres.

In 2000, Joe Johnston spearheaded a development plan that met his parents’ and brothers’ goals: to be walkable, to break down barriers between people, and to create a simpler, richer life. Narrow tree-lined streets and pathways connect homes, farms, gardens, school, parks, and commercial areas in a network designed to resemble a traditional village.

“We had friends that lived in Agritopia,” says resident Belinda Belanger, “and we spent a lot of time in the neighborhood. There was always something going on, and we hated driving home late at night when everyone else was just walking across the street or jumping on their bikes.

“We look forward to ‘pick your own’ days in the orchard, and we like the honor system at the farm stand,” Belanger continues. “I can’t tell you how many times we stop just to see what we can take home. There is a sense of peace and serenity that comes from the agricultural surroundings.”

Willowsford, Loudoun County, Va.

About 30 miles outside Washington, D.C., at the intersection of traditional farmland and the suburbs, lies an agrihood that opened in 2011. Willowsford is now one of the biggest agrihoods in the country. Half of its land consists of open space; the rest contains four villages, with neighborhood parks, amphitheaters, sledding hills, dog parks, campsites, resort-style pools, and a network of trails.

Willowsford Farm grows more than 150 varieties of vegetables, herbs, fruits, and flowers; raises several breeds of livestock; hosts classes and dinners; and markets its products through a CSA program, a farm market, and by wholesaling to restaurants.

The farm is what attracted Jill Nolton and her family to Willowsford. “We love how we are able to engage with the farmers and see where and how they grow food,” she says. “I love that our children are able to understand where whole foods come from. They truly understand what eating seasonally, locally, and sustainably means. We volunteer on the farm, and we pick up our fresh produce through our CSA share at the farm stand, which is a dynamic neighborhood gathering point. We take cooking classes that incorporate fresh farm ingredients, and our kids take them, too.”

Willowsford set up a nonprofit that owns the farm and open space and that hired the director of farm operations, Mike Snow, who has been there from the outset. “While I have no equity in the farm, I also have no debt,” he says. Snow has been given significant autonomy in his quest to make the farm self-sustaining by the time the last home sells.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A House Needs to Breathe...Or Does It?: An Introduction to Building Science

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid

Pretty Good House

View Comments

I wish an Agrihood had been available when I purchased my first and second home. As it is, I have to drive 10 to 30 miles to farmers markets which offer scant organic choices and are only available is summer months. I can see the governing of such communities becoming difficult, but it's a worthwhile paradigm shift in community living and I hope it works and becomes more the norm.