Long-Lasting Gravel Driveways

Get the drainage and base right, and gravel can be an economical alternative to asphalt.

Synopsis: Author David Crosby has built unpaved roads in mountains, deserts, forests, coastal regions, and swamps. Each location is unique, but Crosby has found that problems with unpaved driveways are the result of one or more of the following: bad design, moisture, or unsuitable soils. In this article, he discusses how to avoid these problems. He includes instructions on conducting tests for soil composition and moisture content, and he explains how to design a driveway to drain properly.

When John Denver sang, “Country roads, take me home,” he probably wasn’t singing about paved roads. There’s a certain charm to an unpaved road or driveway that you just can’t get with asphalt. Of course, it doesn’t hurt that gravel is also far less expensive up front and over time, and that if you ever have to remove or realign a gravel driveway, you can just rip it up, rake it out, and re-vegetate.

Because many people opt for a gravel driveway as a cost-saving measure, it tends to be used as an excuse for poor site prep and installation. But that’s a missed opportunity, because site prep and installation mean the difference between a job so good you never notice it and a hassle that you live with because you can’t afford to fix it.

Like any unpaved road, a properly built gravel driveway is as much art as science. It’s not just dirt and rocks; it’s a built structure. The right approach may vary not only from state to state or climate to climate, but possibly from one end of your property to the other. Depending on where you are, the available materials will differ, as will the site conditions, drainage, and existing soil types.

I’ve built unpaved roads in mountains, deserts, forests, coastal regions, and swamps, and they all have held up well. Every job was unique, but there were always basic principles to apply and common mistakes to avoid. In my experience, most problems with unpaved driveways can be traced back to one or more of these three things: bad design, moisture, or unsuitable soils.

Well-graded works best

Compared to the scholarly works that have been published on the subject of structural fill and road base, what is offered here is a gross oversimplification. Still, the principle remains: A good subgrade for an unpaved road is analogous to the foundation of any other structure. To achieve the desired strength and stability, the subgrade should be well graded, meaning that a mixture of stone, gravel, coarse and fine sands, silt, and clay exists in the right proportions.

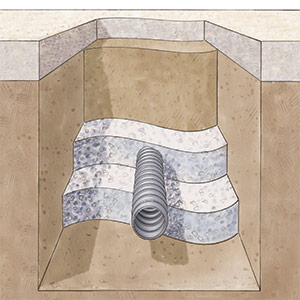

The idea is that the stone and coarse gravel provide a lot of the bearing capacity, the sand fills in the different-size spaces between the stone and gravel and helps with drainage, and the fines (silt and clay) bind everything together. That’s in a perfect world. In the real world, where money matters and sometimes we have to use whatever is available, it’s still possible to build a good driveway.

If after you remove the layer of organic soil the native soil seems dense and well graded, you might not have to do anything more to this layer of the driveway. Often, though, it needs some attention. Be on the lookout for poorly graded, loose, highly plastic soil. If the soil has too high a moisture content to properly compact, it will need to be flipped and possibly augmented before smoothing it out and recompacting. You also might need to bring in granular material to help with drainage, such as 3-in.-minus gravel, which is a mixture of rocks sized from a maximum of 3 in. down to dust. In some cases, you might need to import all of the material for this layer.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: