Do I Need a Vapor Retarder?

Most buildings don’t need polyethylene anywhere, except directly under a concrete slab or on a crawlspace floor.

Every couple of weeks, someone emails me a description of a proposed wall assembly and then asks, “Do I need a vapor retarder?” The short answer I give is that if the wall doesn’t have a vapor retarder, then there probably is no need to worry. It’s rare for a building to have a problem that’s caused by water-vapor diffusion. (Vapor retarders slow vapor movement and have a permanence rating of between 0.01 and 1. With a permanence of less than 0.01, vapor barriers essentially halt vapor flow.)

Water vapor is water in a gaseous state—that is, water that has evaporated. The passing of water vapor through building materials is known as vapor diffusion.

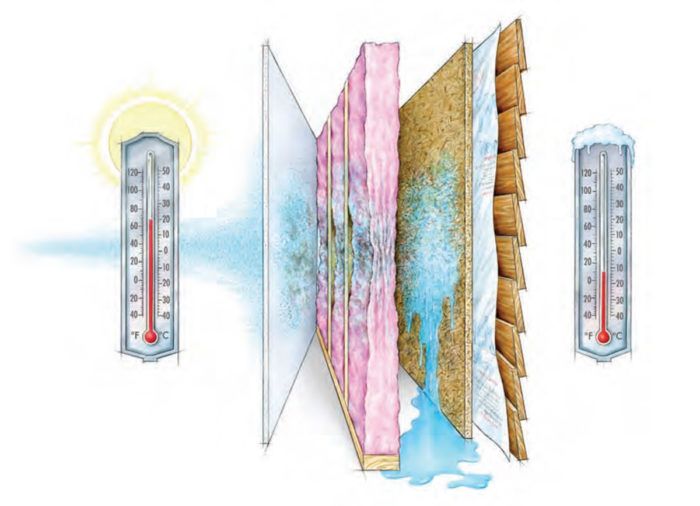

From the 1970s through the early ’80s, builders were taught that it was important to install a vapor barrier (usually polyethylene sheeting) on the warm-in-winter side of wall insulation and ceiling insulation. Many textbooks and magazines explained that this step was necessary to keep the walls dry during the winter, and that any walls without vapor barriers would get wet because the vapor would condense when it hit a cold surface (for example, the interior face of the sheathing).

This was bad advice for several reasons, although there are exceptions, which I’ll get into later. Outward vapor diffusion during the winter almost never leads to wet walls or ceilings. In conventional walls or ceilings, the problem is almost always due to air leakage, not vapor diffusion. Far more moisture is transported by air leaks than by vapor diffusion. And since it prevents wall assemblies from drying inward during the summer, an interior polyethylene vapor barrier can actually make the wall wetter than it would be without the poly.

Worry about air, not water vapor

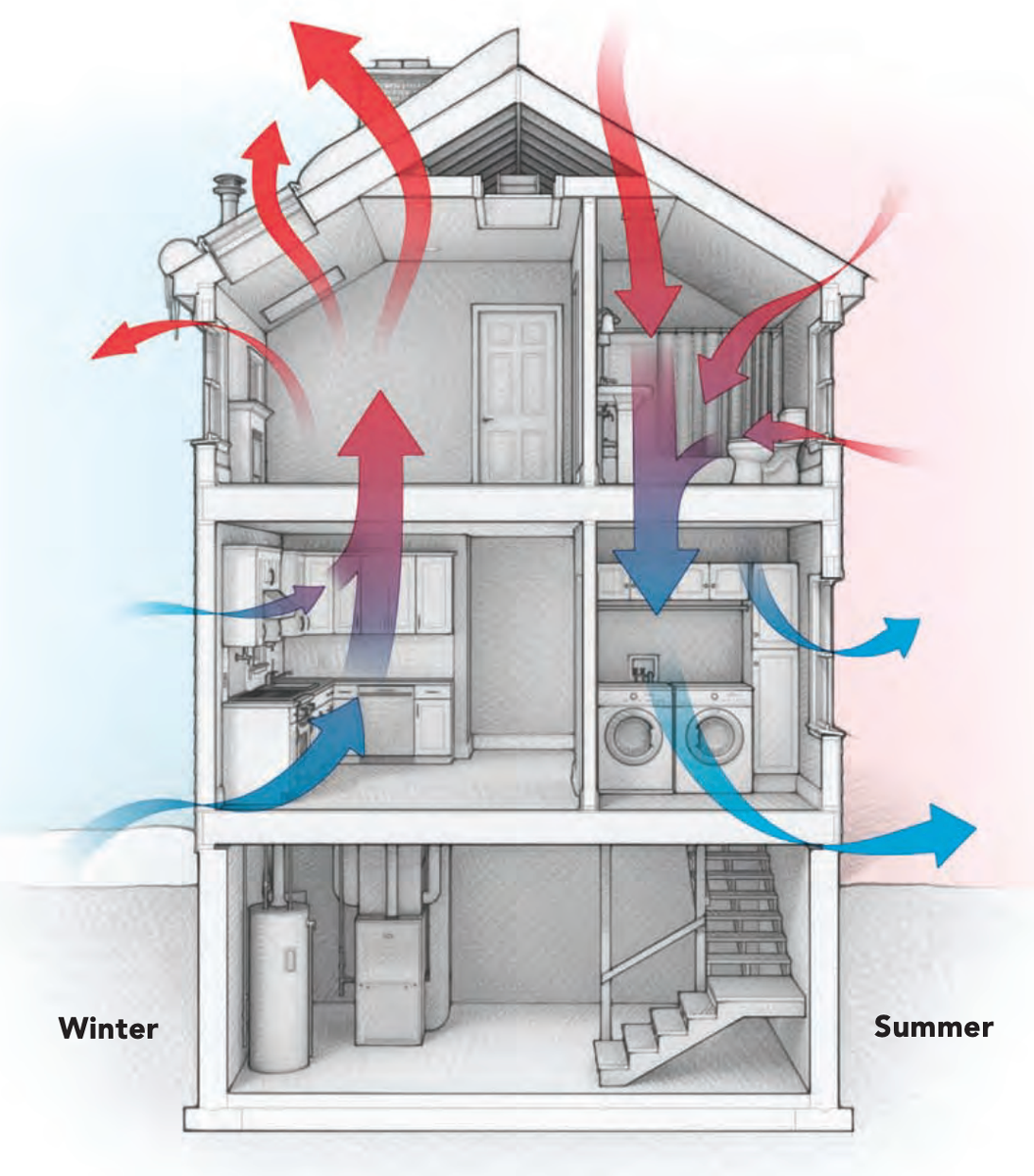

Holes in the drywall (which usually serves as the interior air barrier)—such as around electrical switches and outlets, lights, and at the bottom of walls—can admit far more moisture than will diffuse through the drywall as vapor. Airflow can reverse seasonally.

Air leakage and vapor diffusion create wet walls in different ways

Water vapor can diffuse through vapor permeable materials—for example, gypsum wallboard—even when the wall assembly is perfectly airtight. If the air on one side of the drywall is hot and humid, and the air on the other side of the drywall is dry and cold, the drywall absorbs moisture from the humid side. Once the drywall is damp, some of its moisture evaporates from the side facing dry air.

Air leakage is a different phenomenon. A hole in the drywall (at an electrical box, for example) allows warm interior air to enter the wall cavity and then escape through cracks in the sheathing. This is especially likely to occur if there is a strong driving force such as the stack effect or a fan that is pressurizing the house. If the wall sheathing is cold, some of the moisture in the air may condense on the sheathing or cause the sheathing to absorb moisture. If the sheathing gets sufficiently wet, rot and mold can result.

From Fine Homebuilding #264

From Fine Homebuilding #264

For diagrams and more information on when vapor diffusion causes trouble, click the View PDF button below.

View Comments

If a vapor barrier membrane was applied to the exterior side of sheathing would there be concern for the ability of the sheathing to dry during cold or hot seasons particularly in climate 6? The wall assembly I'm thinking of goes like this from exterior to interior....cladding, rain screen, 2-3 lays of staggered joint XPS, polyurea membrane applied, SIP panel, drywall, paint. Thanks for the article, very informative!