Markup: The One Number That Rules Them All

One markup controls the revenue for your construction business. This one markup rules all other markups you might have developed.

The lines below are from J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic piece of fantasy literature The Lord of the Rings. They describe the power of the One Ring.

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.

The One Ring, created by the Dark Lord Sauron, had the power to control the wearers of the other magical rings.

The One Ring ruled them all.

Much like the One Ring, one markup controls the revenue for your construction business. This one markup (also known as markup factor) rules all other markups you might have developed.

Markup is the amount of money added to the COST to get a PRICE.

COST x MARKUP FACTOR = PRICE

(Ex. a 20% MARKUP = 1.2 MARKUP FACTOR)

The markup for your business needs to be enough to cover the cost of your EXPENSES and leave you with a PROFIT.

The difference between the PRICE and the COST is the PROFIT.

PRICE – COST = PROFIT

The MARGIN refers to the percentage of PROFITS in relation to the PRICE.

PROFIT/PRICE x 100% = MARGIN

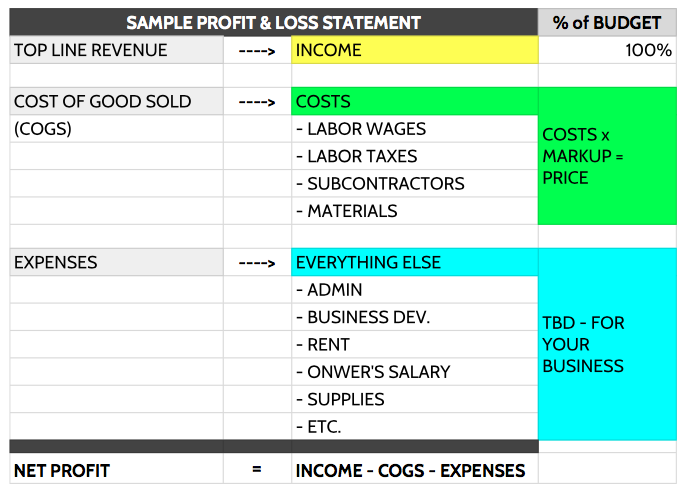

These equations are the basic formulas that you need to know to analyze your Profit and Loss (P&L) Statement.

The sole focus of this post is the markup for your business. (I will review how to calculate and utilize your margin in my next post.)

The figure below is a simplified P&L statement.

To have a profitable business you must follow this simple rule:

Apply a markup factor to your costs to determine your price so that you can pay your expenses and have a profit remaining.

The formula looks like this:

(COST x MARKUP FACTOR) – COST – EXPENSES > 0

This is your business plan in a nutshell. Your business strategy does not have to be more complicated than the above rule.

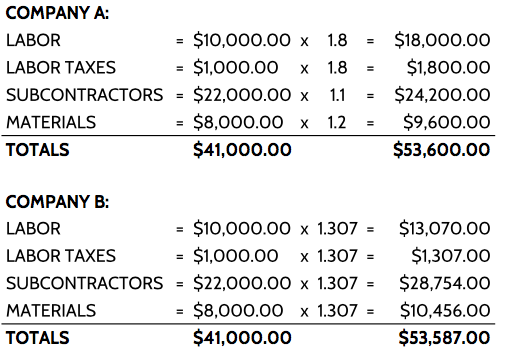

Many construction business owners use multiple markups for various cost categories. This is a waste of time and effort.

Your business has only one markup. You do not need to use multiple markup factors.

For example:

Company A uses multiple markups, and Company B use one markup.

Company B uses one markup factor for all costs and gets the same result as Company A.

This method will make Company B’s proposals and budget more accurate and consistent over time.

Simplicity is your friend when applying a markup.

DETERMINE THE MARKUP FOR YOUR BUSINESS

Take a look at your P&L statement for last year.

What was your total revenue?

What was your total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)?

Divide your total revenue by your total COGS.

TOTAL REVENUE/COGS = MARKUP FACTOR

This is the only markup you have for your business. This markup rules all other markups.

Now that you know your cost, total revenue, and markup, you can perform a quick analysis.

Was that markup enough to pay all your expenses and leave you with a profit?

If not, you need to increase your markup, reduce your costs, reduce your expenses, or a combination of all of these items. There is one markup to rule them all.

J.R.R. Tolkien took over twelve years to write The Lord of the Rings and develop the idea of the One Ring. You don’t have that kind of time to understand the One Markup for your business.

View Comments

I think that you are really oversimplifying things. Your premise is that your ratio's of services remains the same. If you use the above premise you will very quickly find yourself overbidding some jobs and underbidding others. The single markup only works for very simple projects.

Totally agree with BrianSmith. If you are roofing or siding, sure, one markup (or better yet, margin) factor is fine for everything, but on other jobs you'll be losing work. Example: client wants new stone tops. My supplier charges me $5000. $500-1000 markup is reasonable if the supplier fabricates and installs it. I don't have to do anything other than push a little paper after the initial meeting. But if I put a 35% gross margin on this like I do for my basic labor, the price mushrooms from $5500-$6000 to $7700, which is going to be way out of line with anyone else bidding the job. We use a flat margin factor (based on overall job size) and make exceptions for big ticket items like subcontractors and stone, cabinets, etc.