Split Jacks When Framing a Window Opening

Split jacks let you work faster, but they introduce another hinge point in the wall, which could be problematic in high-wind and high-seismic-risk zones.

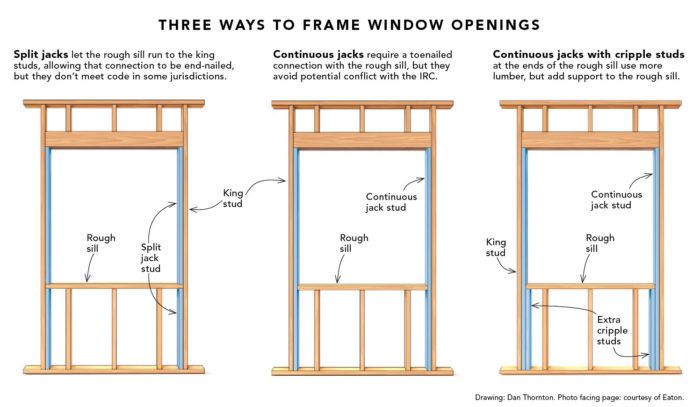

When framing a window opening, should the jack or trimmer studs be continuous, or should they split around the rough sill?

—Jerry Riga, via email

This is an interesting question with no clear answer. Jack studs (or trimmer studs—the name depends on where you’re located), provide the load path from the header to the bottom, or sole, plate. Not even the IRC is clear about whether they can be split. Section R602.3 reads, “Studs shall be continuous from support at the sole plate to a support at the top plate,” but then includes an exception for “jack studs, trimmer studs, and cripple studs.” The wording is tricky. It could be that the IRC makes this exception because jacks are always cut shorter than regular stud height in order to fit below the header, or it could mean it’s OK for the jacks to be split around the rough sill. While all the drawings in the IRC show continuous jacks, and many inspectors will fail split jacks, this appears to be a regional preference.

Some carpenters like split jacks because it allows them to nail through the king stud into the end of the rough sill (with continuous jacks, the connection to the sill is normally toenailed), and the lower portion of the split jacks support the rough sill without having to add cripple studs. Simply put, using split jacks lets you work faster.

However, split jacks do introduce another hinge point in the wall, which could be problematic in high-wind and high-seismic-risk zones. Another issue is the horizontal wood grain in the rough sill. Wood has much more compressive strength parallel to the grain than across it, so there’s a chance of the rough sill crushing under, say, a heavy snow load. The counter to this point is that all the plates and the header run horizontally, so what’s the difference?

Although it is frowned upon by advocates of advanced framing—who strive to avoid all unnecessary framing—you could also run the jacks continuously and add cripple studs below the ends of the rough sill. This supports the sill and avoids unwanted conversations with your inspector, although placing lumber where insulation could be installed increases thermal bridging.

View Comments

I suspect that the IRC considers the king stud to carry all the lateral wind load since it acts as a pinned beam form the top plate to the bottom, thereby simplifying the load path and design. The connection from the header to the jack acts as a hinge point so the jack is typically not considered to resist wind loading. I have two arguments against splitting the jack. The first is that though you are correct about the perpendicular grain resistance being lower than parallel to grain. Your comparison to the top and bottom plates is erroneous. The perpendicular to grain resistance depends on how close the applied load is to the edge of a board. When the compression is right at the unsupported edge of the sill there is a higher tendency to crush than say if the load were applied away from the edge. The second argument is one of durability. I would argue that the window sill has a somewhat higher potential for rot than the sole plate so by splitting the jack and placing the end grain of the jack stud ( a structural member) in the plane of higher rot potential is less desirable location than running it to the bottom plate.

"Another hinge point in the wall". Seriously? Is this hinge effect not negligible compared to the shear bracing provided by a properly sheathed and nailed wall? Seems like that hinge effect is way off into the margins, but I am happy to be told how I am wrong and learn.

All these are good points, but arguably of very little actual effect, especially if the jack studs are nailed to the king studs like we practice. We try to avoid toenailing an unsupported joint like with the continuous jack stud, where you need to keep things straight and level.