Building to Survive in Wildfire Country

Don’t get burned: The right materials and details are a start. Landscaping and regular maintenance can help. But even these steps sometimes aren’t enough.

Synopsis: In this special report, contributing writer Scott Gibson takes a look at the devastation left by the 2017 California Wildfires, and addresses whether code requirements saved some dwellings, and whether a review of the building codes is due in the wake of the devastation. He describes the differences between combustible, noncombustible, ignition-resistant, and fire-resistant materials and where they should be used. The article includes an illustration of defensive details to give a home the greatest chance of surviving a wildfire, including recommendations for landscaping, roofs, windows, and doors, and outbuildings. Photo above: iStock.com/Jorge Villalba

If you want to build a house in the state of California, you’ll first have to consult a set of maps to find out whether the property is in what’s called a “fire hazard severity zone.” If it is, you’ll be required to follow specific construction guidelines designed to minimize the chance the house will burn down in one of the many wildfires that sweep through the state every year.

These rules, which are part of the California Building Code and are spelled out in the International Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Code, address everything from roof coverings and window glass to vent openings on eaves and cornices. In tandem with landscaping practices that keep combustible vegetation safely away from buildings, the WUI (pronounced “woo-ey”) building codes offer a relatively effective way of protecting buildings from fire. Except wildfires don’t always follow a script.

Last October, what became known as the Wine Country or North Bay fires in Northern California burned over 210,000 acres of land, wiping out more than 8,000 structures and killing at least 42 people. It was the most destructive wildfire event in the state’s history. As state officials at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) were sorting out those details, another major blaze struck—the Thomas Fire in Southern California. The blaze burned at least 270,000 acres to become the third-biggest fire in state history, and it struck well outside what fire experts had considered California’s normal fire season.

There’s no doubt that WUI code requirements saved some homes from destruction, though just how many is impossible to say. In Santa Rosa, the 2800 structures that burned to the ground in October weren’t even in an area deemed to be at high risk. Whole neighborhoods left in smoking ruins weren’t included on state or local fire-hazard maps. In effect, they were located in an area considered unburnable.

And that raises some questions for code officials, builders, and homeowners in California as well as in other states with areas prone to wildfires: If the property is not included in a fire-hazard zone, do you build to the WUI requirements anyway? What remedial steps can or should be taken for houses built before wildfire codes were enacted? Do the codes go far enough? Should some areas simply be deemed too risky for construction?

“It’s not just that the building codes need to be revisited,” says Max Moritz, a wildfire researcher with the University of California Cooperative Extension. “It’s also, on a broader scale, how and where we’re building our communities.”

How houses catch fire

Building codes for WUI zones are aimed at preventing three ways houses can ignite during a wildfire—fires caused by sparks from burning embers pushed ahead of the flames by wind, those caused by radiant heat from nearby buildings or objects that have caught fire, and those caused by direct contact with flames.

David Shew, staff chief for planning and risk analysis at Cal Fire, considers embers to be the most dangerous, accounting for 70% to 90% of the houses lost to wildfires. Smoldering firebrands can blow up to a mile ahead of advancing flames, and they don’t need much of a toehold to start a fire. Any nook, crevice, or overlooked recess in the skin of a building can harbor an ember. With that in mind, many of the provisions of the building codes are aimed at preventing the intrusion of burning embers into or under structures where they can ignite combustible material.

Embers are not the only risk, though. When the house next door catches on fire, the immediate threat is radiant heat that can shatter windows and ignite combustible building materials inside as well as outside the house. So state or local authorities may require fire-rated exterior doors, dual-glazed windows with one tempered pane of glass, and noncombustible or fire-resistant wall coverings.

The other key is vegetation around and near the house. California law requires that all flammable vegetation be removed within 30 ft. of buildings, according to Cal Fire. Vegetation within 100 ft. of a building must be modified to create a “defensible space” that gives firefighters enough room to fight a fire.

With so many houses lost to fire in 2017, and the fire season now stretching into months once considered safe, some review of both WUI codes is all but inevitable. “Probably, overall, it is a little soon,” says Shew of potential changes to WUI codes, “but there are a lot of groups that are already talking about a list of lessons learned.”

A review of state fire-hazard maps was already planned for 2018 before the fires struck last fall. According to Moritz, the next generation of hazard maps should do a better job of incorporating wind patterns that have been altered by climate change. At the least, he says, buffers between WUI areas and densely populated urban areas should be wider than they are now. “We don’t need to put LA in a WUI zone,” he said, “but under some conditions [the boundaries] have to extend farther into the built environment than they currently do.”

What about existing houses?

Building codes can make new houses more fire resistant, but that doesn’t do anything to protect existing houses in WUI zones. Michele Steinberg, wildfire division manager for the National Fire Protection Association, puts it this way: “The problem is already out there. It’s already been built. It’s already been designed, so what the heck do we do with it? It’s extremely challenging to go in as a regulator and say, ‘Hey, you’ve got a wood roof and you’ve got to change it out.’ That doesn’t go over real well.”

Some retrofits are easy. Removing vegetation around the house or cleaning out gutters and installing leaf guards is essentially free if a homeowner doesn’t count his or her time. But replacing a wood-shake roof with a noncombustible material is not only expensive but beyond the skills of most homeowners, points out Steve Quarles, chief scientist for wildfires at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS). Many other changes that could make houses less fire prone—such as sealing soffits and closing off underdeck areas—may be beyond the means or skills of many homeowners.

Little, if any, federal money is available to homeowners to mitigate fire risks on existing homes, Quarles says, in part because it’s hard to quantify a return on investment for retrofits. Although insurance companies may become a more powerful driver in forcing homeowners to add fire-proofing details, many homeowners are now forced to make the decision and pay for alterations themselves. The question extends to houses that will be rebuilt in areas not currently included on fire-risk maps: Should the Coffey Park neighborhood of Santa Rosa be rebuilt to WUI codes even if it isn’t included in recognized fire-risk areas? Santa Rosa officials are now weighing that question, says Shew. “It’s easy in the immediate aftermath of an event like this to stand firm and say we’re going to require all of these new things,” he says. “But there’s always a fiscal impact of doing that. If the city were to say, ‘we want to require it,’ but it’s not in a zone that requires that standard, would the insurance companies pay for it?”

We need more-resilient communities

Planners have long believed that houses in an urban area should be protected from fire by a buffer strip separating them from a high-risk WUI zone. People came to assume that urbanized areas were basically unburnable.

“Well, guess what?” says Steinberg. “When you get embers into these communities and you have homes close together and plenty of decorative fuel, you don’t have to be next to a forest to have impacts.”

The bottom line, says architect David Arkin, is that no house will survive extreme conditions. “Under certain conditions, the most supposedly fireproof building will not survive,” he says. “That’s when 70 mile-per-hour winds are whipping trees into cyclones of fire. First and foremost, under certain conditions no building type is going to survive.”

Albert Simeoni, a professor of fire-protection engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, says historical data that guides construction is losing some of its value because climate change is reshaping how fires behave. Hardening structures against fire is a good first step, he says, but it’s not enough. Communities should be designed more thoughtfully, so houses are interspersed in areas with noncombustible materials—parking spaces, for example, or gardens and common spaces. That would slow the spread of a wildfire and break it into smaller, more easily managed blazes.

Some sites are simply unsuitable, or at least unsafe, for construction, Shew says. For example, houses should not be built at the top of “natural chimneys,” where the terrain funnels intense heat uphill as tinder-dry chaparral burns. People want to build on these sites because of the views, but moving a house even a little bit can preserve panoramic views while protecting the house more effectively from fire. “Understanding the principles of how fire will behave on a certain piece of ground and the location of where the house can be placed will minimize the risk of a fire impacting a house,” he says.

The other wild card is the way in which climate change is exacerbating the threat. “We’re referring to it as the new normal, where we fear this is more the norm of what we will see in the future, not the exception,” Shew says. “There’s no question those impacts are real. What we used to refer to as ‘fire season’ was probably 40 days less than what we see today. There will be people working on the fire lines on Christmas Day. We’ve never seen that before.”

What’s the difference?

Combustible, noncombustible, ignition-resistant, and fire-resistant materials

When researching, designing, and choosing materials for a home in a wildfire-prone area, you’ll likely encounter these four terms. Though the definition of “combustible” materials may seem obvious, “noncombustible,” “ignition resistant,” and “fire resistant” materials are each slightly different, even though they often can serve the same function. Here are some basic definitions to help you in your quest for a fire-safe home.

Combustible: Materials that ignite and burn easily are known to be combustible. They are also likely to release flammable vapors that support further combustion during a fire. Many common building materials are combustible, including wood, wood composites, and plastics. Combustible materials should not be used on the exterior of a home in a wildfire-prone area.

Noncombustible: By passing certain ASTM test criteria, materials like concrete, brick, most metals, and glass are rated noncombustible, and as such are known not to ignite, burn, or release combustible vapor during a fire. Noncombustible materials are the best option for a fire-safe exterior.

Ignition resistant: This designation is typically used for manufactured products like roof shingles and treated lumber and certifies the amount of time they take to ignite and the rate at which flames will spread over them during a fire. Because ignition-resistant materials are not naturally noncombustible, they are subject to accelerated weatherization during testing to make sure their performance is consistent over time. Sometimes building assemblies are rated as ignition-resistant, though it is more commonly a designation for materials.

Fire resistant: This rating is commonly given to materials and assemblies that are desiged to contain fire and retain structural integrity, offering time for occupants to escape and for firefighters to arrive. This rating is therefore often accompanied by a specific time. Some exterior doors, for example, will have a fire-resistance rating of 20, 45, 60, or 90 minutes.

Defensive details

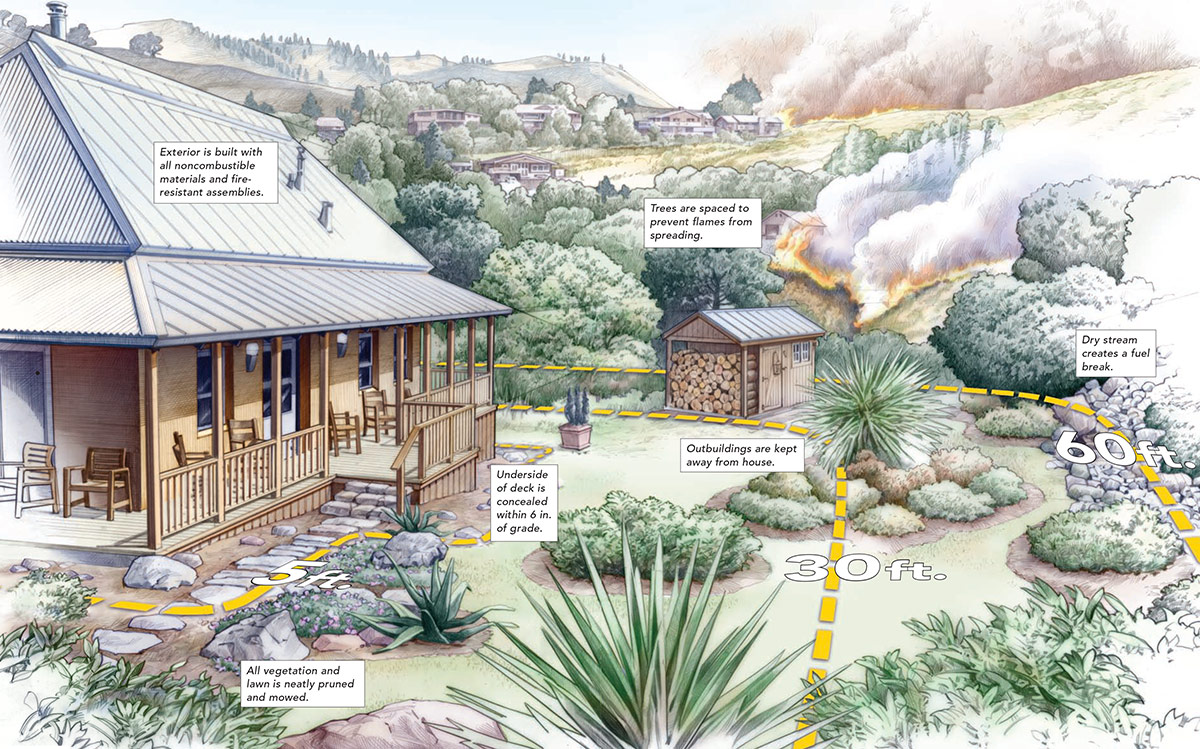

To design and build a house with the greatest chance of surviving a wildfire, consider exterior materials, landscape details, and regular maintenance. Note that while some of these details are prescribed by codes, all are considered best practice for homes in wildfire-prone areas.

HOME

- Roofs can either be protected by a material with a Class A fire-resistance rating—which includes clay, concrete, and slate, as well as many types of asphalt and metal—or by a fire-resistant assembly. For example, Class B wood roof shingles can be used over a Class A underlayment. If a roofing material is open at the eaves, as is the case with tile and some metal roofing, these gaps should be sealed. Valleys must be continuously covered by a Class A material, so with asphalt shingles a woven or cut valley is preferable to an open valley.

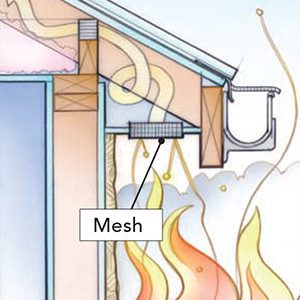

- Eaves should be built with ignition-resistant or noncombustible material. Metal and fiber cement are viable options for soffit and fascia details. All exterior vents should be covered with 1⁄8-in. mesh to prevent embers from getting into the house. Another option is a commercially available product like the Vulcan Vent.

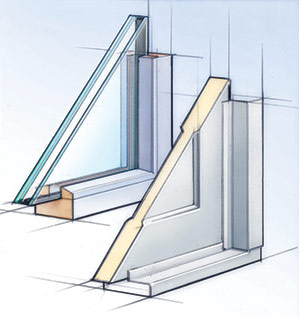

- Windows and all other glazing should be fire rated or multipane with at least one layer of tempered glass.

- Doors should be fire rated or built from noncombustible or fire-resistant materials.

- Decks are allowed to have wood framing, but should be finished with a fire-resistant material that extends down to within 6 in. of the ground. Cantilevers and other overhangs should be built and finished with noncombustible materials and details as well.

LANDSCAPE

- A noncombustible area within 5 ft. of the home should have no vegetation or structures that may ignite and spread flames. Use gravel, brick, concrete, or stone as ground cover around the house.

- Trees should be spaced to minimize the spread of fire. All treetops should be kept a minimum of 10 ft. from the house. Within

10 ft. to 30 ft. away, treetops should be spaced at least 18 ft. apart. In the area 30 ft. to 60 ft. from the home, treetops should be at least 12 ft. apart. And treetops 60 ft. to

100 ft. from the home should have at least 6 ft. between the tops. Trees on a sloped site should be spaced even further apart. - Outbuildings, fences, pergolas, and other structures should be kept away from the house. Though the code may allow them to be built with any material, it’s a good idea to build with noncombustible ones.

- Fuel breaks should be created throughout the landscape to prevent a fire from easily spreading. Common options include driveways, noncombustible walks, patios, and dry streams.

MAINTENANCE

- Gutters should have leaf guards and be kept clean of combustible debris.

- Roofs should be kept free of leaves, sticks, and other combustible debris.

- Lawns should be neatly mowed to below 4 in.

- Vegetation should be kept trimmed around sheds, decks, propane tanks, and other outdoor items.

- Sprouts and saplings below mature trees should be removed.

- Mature trees should be pruned away from the ground, and all dead plants should be removed.

A straw-bale survival story

Fire-resistant details like those in California’s building codes can make conventional woodframed houses safer in the event of a fire. But other types of construction may be inherently better. One of them, according to David Arkin, an architect in Berkeley, California, and director of the California Straw Building Association (CASBA), is straw-bale construction.

A few weeks after the Tubbs fire in Northern California last October, Arkin passed along a hairraising email he’d received from a client whose strawbale house successfully weathered the event. Edward Doody woke up in his Mendocino County home at 2:30 in the morning as fire approached. He decided to make a run for it with his dog, but their escape path was blocked, so Doody and his neighbor retreated to the house and waited out the fire.

“Huge booms resonated through the night air as propane tanks exploded, igniting more houses throughout the night,” Doody wrote. “The overused analogy to a war zone comes to mind.”

Doody’s house survived. His neighbors’ did not.

“We’ve observed with our own straw-bale and earth homes, and have heard stories of other similar buildings, that plastered walls combined with a metal roof and other fire-resistant detailing, and with a defensible space around the buildings, offer a good chance of surviving a fire,” Arkin says, “and we’ve seen these homes survive in situations where nearby homes were lost.”

Arkin says an assembly consisting of rice straw bales stacked on edge and finished with lime-cement plaster achieved a two-hour fire rating in one ASTM test, at least double what might be expected from a standard stick-framed house. “That does not automatically mean that all other straw-bale wall assemblies meet a two-hour rating,” he says. “ But can we conclude that they are likely more fire resistant than most other typical residential wall assemblies? Yes.”

For more information

The National Fire Protection Association’s Firewise USA program (www.firewise.org) offers recommendations for building materials and construction details to reduce the risk of fire.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) is the state agency responsible for fire protection and hazard mapping. Its website (calfire.ca.gov) includes information on vegetation management and wildland building codes.

The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) has published a series of regional retrofit guides explaining how existing buildings can be fortified against wildfires. Guides can be downloaded for free on their website (disastersafety.org).

From Fine Homebuilding #274

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Smart String Line

Anchor Bolt Marker

Get Your House Right: Architectural Elements to Use & Avoid

View Comments

David Shew, staff chief for planning and risk analysis at Cal Fire, considers embers to be the most dangerous, accounting for 70% to 90% of the houses lost to wildfires.

Authorities called for Mandatory Evacuation. An ember would land on someones property and start a small fire that could be put out with a bucket of water. Fire trucks were spread out. They could not detect a fire until the house was almost fully involved. This is why you would have one house destroyed while the rest of the neighborhood was untouched. The point is, the home owners left their homes unprotected when they could have easily saved them.

My both sides of my family have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area and Northern California since the late 1800s. So forest fires and the kind of urban fires that have regularly damaged the Berkeley hills and lower Marin County are not unfamiliar to me. My mother past away two years to the month prior to the Tubbs fire. The Tubbs fire came to within a typical 5 to 10 minute drive on Santa Rosa's rather heavily travel main boulevards, that provide the only real egress from the neighborhoods west of Highway 101, from the condo she lived in for nearly 30 years. A cousin's daughter and son-in-law lost their home on the East side of 101.

The condo complex my late mother lived in had only one narrow exit, with multiple feeder lanes into it, facing north toward the direction the Tubbs was coming from onto a divided four lane boulevard. Santa Rosa's housing developments since the early 1980s have been rather haphazard and largely developed on the cheap and on what ever former farm and ranch land a developer could get their hands on. These neighborhoods and condo / townhouse developments tend to be self contained, isolated and not directly connected to neighboring residential neighborhoods down on the flat lands of Santa Rosa.

If I recall correctly from Bay Area news agencies, the Tubbs fire burst into Santa Rosa from out of the northeasterly direction moving south-southwest more or less and at a rate of 300' to 500' per second at its worst; animals were found charred to death where they stood.

In fire conditions like that, delaying to evacuate to put out an ember with a bucket of water was certain suicide. Many who died in California's fires last Fall had the cruel fate of lack of time, from the time they knew of they were in danger, to even get out of their garages let alone any distance from their homes.