How to Budget Home Construction on Target, Every Time

Bucking industry norms, these builders stay on budget with up-front, fixed pricing on every new home and remodel.

Synopsis: Jeremy Martin from RisherMartin Fine Homes, a custom-home builder and remodeler in Austin, Texas, outlines his company’s process of offering fixed-price contracts for new-home builds and remodels, flying in the face of decades of industry practice. By setting up a preconstruction services department, the company considers all the detailed specs from subs; all the pricing and lead times; all the plans and elevations for every system; and every bit of hardware, color, and finish and creates a comprehensive contract that sorts out all of the possible hidden details before construction begins. Their contracts assume the worst-case scenarios in order to shoot high with estimates and come in under budget. This article describes in detail how they make it work.

Six years ago, my business partner and I went searching for the trifecta of residential construction: being on time and on budget, with happy clients. After a lot of hard work and fundamental changes to our staff and workflow, we created a front-loaded process that is very rare on high-end, architecturally driven home-building projects. When I tell other experienced builders that my firm has now been offering fixed-price contracts for six years on both new homes and remodels, and that we come within 1% of that price on every project and absorb the difference so the customer’s price never varies, they are often incredulous, and for good reason. What we do flies in the face of decades of industry practice, a legacy that most builders don’t have the time or inclination to challenge, and so instead they accept the usual frustrations as part of the process used to budget home construction.

Following the practice of commercial construction firms, we created a preconstruction services (PCS) department, staffed by two specialists. Where most residential contractors have maybe one estimator bidding on up to 50 jobs each year, we have two PCS managers putting together incredibly detailed contracts on 10 or so projects per year. We call our finished contract “The Book,” and it can run anywhere from 200 to 800 pages for a single project. All specifications, selections, and pricing are identified in advance, with pictures and specs of everything in the house, detailed plans and elevations for each system, and specific timelines for every stage. While we do create allowances for hidden conditions and other factors that simply cannot be fully predicted at the outset, we create fewer of them than other builders do, and we shoot high with our estimates, ensuring we’ll be giving time and/or money back if anything, never the opposite.

It took us a long time to develop the systems and templates we rely on today. And perhaps not every firm in every market can take it as far as we have. But in our opinion, everyone in our field should have fixed-price contracts as their goal. It’s a win for clients—delivering

less risk, less stress, more enjoyment, and more satisfaction. We know this because we ask each of them to complete a detailed questionnaire after their project is complete, and we make all of those surveys—not a cherry-picked few—available to every customer. Fixed-price bidding is also a huge win for our company: We get a much clearer path to contract, better efficiency and profitability, and happier employees.

Nationwide, we know many other talented builders and remodelers executing similar projects with fixed-price contracts and incredibly detailed scopes of work and specifications, which means that we are not an anomaly; it can be done. The following is how it works for us, and how we made it happen.

A key role

Our old process might sound familiar. We and a few other custom builders would be asked to whip up a free “estimate.” We’d spend a couple of months refining the project scope and iterating on the budget, and if we won the job, we’d sign a “cost-plus” contract with our clients. That might be a contract that is fixed-price in name, but invariably, the scope would evolve as the project progressed, as would the so-called “budget” and “schedule.” It was frustrating for everyone involved, and tensions would rise as projects moved along.

It’s important to note that like most builders, we were working very hard on behalf of our clients, being transparent and acting in their best interests at every turn. Despite our best efforts, conversations almost always became difficult—“When are you going to be done and what’s this going to end up costing?” Even with a month to go, we weren’t 100% sure. When we decided to commit to fixed-price bidding, we had one goal: We wanted to be able to answer those simple questions—exactly what will it cost and exactly how long will it take—before construction began.

Converting to fixed-price contracts required significant up-front cost, in both dollars and time. For a start, we created a bigger back office, with our critical new PCS department. Where an estimator might bid on dozens of jobs a year, acting on educated guesses, the PCS managers engage the client, architect, structural engineer, interior designer, and subcontractors in an ongoing conversation and are always looking for gaps in information and methods.

For this to work, our subs need to create fixed-price bids also, and they only get one bite at the apple, so they rely on the work of our PCS department to produce accurate specifications. It took a lot of education to get our subcontractors to work this way. The PCS managers check all those bids to make sure they are complete, clarifying the gaps where trades come together and might wonder who is doing what.

Throughout this process, the PCS department continues to check in with the designers, subs, clients, and our construction department to make sure everyone’s on board, and to be sure the ideas make sense to everyone and that they will actually work on the job site. This is the type of stuff that gets figured out later on most construction projects, like how to wire an unfamiliar light fixture. We figure it out ahead of time.

All of those selections—the detailed specs from subs, all of the pricing and lead times, plans and elevations for every system, installation guides from the manufacturer, every color and finish in the kitchen, every bit of hardware—go into The Book, which is the PCS manager’s key deliverable.

We charge a fixed priced for our preconstruction services—for example, roughly $5000 for a $1 million job—and at first it was a loss leader. But now, with templates made, systems created, software learned, subs and designers educated, and a library of stuff we can reuse, The Book is much cheaper to produce. The benefits are profound. With The Book in hand, all our project manager and subcontractors have to do is purchase supplies and execute.

Of course, the first thing we need to do is set a basic scope of work and ballpark budget, and that starts as soon as a prospective client contacts us.

Budget home construction

We like to meet prospective clients in person and often visit their home as soon as possible. If that meeting goes well, we meet next with the client’s architect to see renderings and concepts, looking closely at the designer’s materials and palette. The follow-up conversation with the client is the crucial one. Before we wade into preconstruction services with our clients, we have to set a level on the budget. We can’t afford to spend six to nine months planning a project that will never get built. It’s a huge waste of resources—for the builder, the client, and the design professionals.

We are honest at the outset about what it’s going to cost; in fact, we tend to shoot high. We do lose jobs at this point to builders who say they can do it for less. (By the way, we often hear from those clients later, telling us the final tally ended up exactly where we said it would be at the start of the process to budget home construction.)

Our ballpark estimate comes in the form of a document called an “Investment Range Proposal.” It sets up the project for success, saying, “As long as you stay in your swim lane—as long as what you end up designing is mostly what we are looking at here—then I can stay in my lane in terms of schedule and budget.”

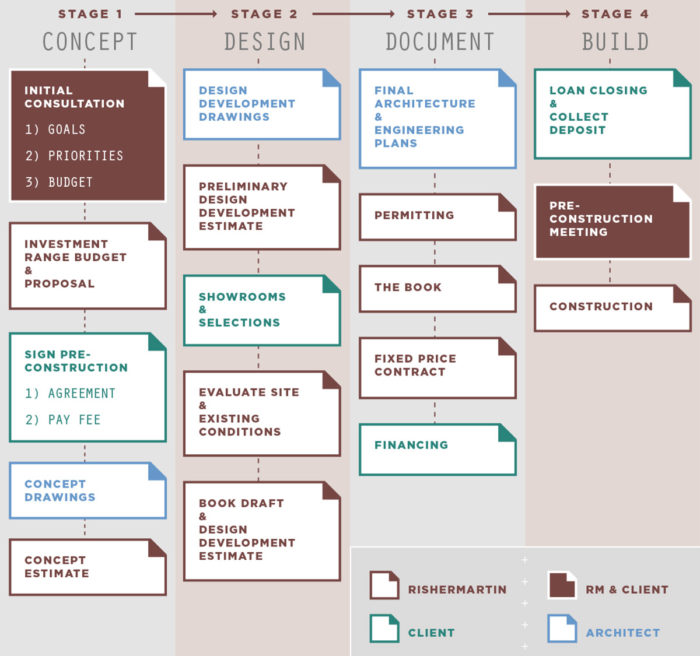

We get paid for preconstruction. We don’t do head-to-head bids with full documentation; we set a ballpark and present our process. If clients are okay with the numbers and trust us, they sign a “Pre-Construction Services Agreement,” paying us a fixed fee for creating the contract, based on the hours we think it’ll take. With that commitment in hand, the real planning moves forward. The architect draws more, the client makes selections on materials and fixtures, and our investment-range proposal narrows. As we work through the details, all uncertainty gets rooted out, and we arrive at The Book, our fixed-price contract with a final number and schedule.

As the project is refined and developed, every time the clients get outside their lane we have a group reality check about what it will mean for deadlines and budget. Each time, we get the client’s permission to either scale back the design or expand the budget and timeline, so these realities stay linked throughout the project. Along the way, the subcontractors all get a chapter of The Book so they can bid on it. That’s the beauty of the system: Everyone is working off the same sheet music. Subs bid to match The Book, and then they keep it and have everything they need to do the job.

When we break ground or start demo, our comprehensive contract starts paying dividends. We spend far less time than we used to putting out fires. Today, change orders amount to less than 2% of the total price on average. That gives us far more time on site managing, scheduling, and monitoring quality.

Imagine this: You rarely stop construction to wait for decisions or selections. You don’t have to tear out and rebuild. You just plow forward, making relentless progress. And your clients don’t have to pay for idle production time while you sort out the details.

Contingencies for hidden conditions

I’m often asked how we handle the unpredictable parts of a project. My answer is that most of the unpredictable things are actually plannable. But if you only have 20 hours to estimate a job, you have no hope of finding them. On the other hand, if you spend the time it takes to root around and investigate, you’ll see the signs of hidden problems. Then, you need contingency plans.

Remodels make up about half of our business. The nuts and bolts of our process don’t change on remodels, though we do have more allowances if we can’t see what’s happening inside the floor, walls, and ceiling. Our biggest risks come with houses that have multiple additions, with each builder adding new plumbing and wiring onto old, in different decades, with different codes. Now you have a subpanel over here and one over there. So we build in an allowance for new circuits throughout the house. We always assume the worst-case scenario in terms of time and money. When the conditions are better than we assumed, the clients get money back.

When you come in under budget or finish ahead of deadline, you get amazing word-of-mouth referrals. Litigation is often about money. If you give money back during a project, there’s rarely a problem. But if you promise a home in 12 months at $1 million and deliver it in 18 months for $1.5, you’re likely to have issues.

The right clients and the right designers

As the builder, you need to be able to have hard conversations with clients up front—to be clear about what things cost—so that in the end, the client pays exactly the right price and gets exactly what they want. And this ensures that our business will make money. The truth is that to keep craft alive, we must keep profitability alive.

It was important for us to realize that not every client is right for us. Our clients need to be able to make decisions up front and trust the builder and designer to be good at what they do. You wouldn’t tell a doctor how to operate, and the case is the same here. Aside from trusting us, the client needs to find an architect they can trust and whose process they feel no need to micromanage.

Most of our clients hire an architect whose homes they love and let them do their thing. Don’t get me wrong: The architects get to know the clients on a deep level, learning what is personally important and meaningful to them. They integrate art, furniture, heirlooms, kids’ rooms, special needs, and lifestyle—everything that matters. But after clients have shared all that, they need to sit back and say, “Now dazzle me.”

Creating a fixed-price bid requires a big shift in the normal design-bid-build sequence used to budget home construction. Usually, the architect and client design the project with little to no interaction with the builder, and then they get multiple bids for construction. The preconstruction process asks the builder to engage the client and design team far earlier than normal in a hybrid design/build process, or what some professionals have deemed “integrated project delivery.”

This front-loaded collaboration is the key to setting the project on a path toward success. After the client hires the architect, we meet with both as soon as possible. It’s critical that we have the triumvirate together before the design happens. We work to set a home construction or remodel budget, and then work backward from that number. Then there are months of iterations on budget, design, materials, methods, timeline, and every last detail before we deliver a finished construction contract. That requires a very collaborative designer. They have to want to work with us early in the process, and welcome feedback. It doesn’t work if there are a bunch of egos clashing.

At the end of every project we have a post-mortem. We go through the budget penny by penny, line by line, so we can find problems and figure out how to make The Book better. Sometimes it’s as simple as, “We always need more dumpsters.” This process only works with continuous improvement.

Thoughts for homeowners

If you want this result, or something close to it, the first step is to hire a well-qualified architect and other design professionals (interior designer, structural engineer, etc.). Pay them a fair fee for the detailed construction documents that you and your builder will need. Don’t be penny-wise and pound-foolish, hoping to cut costs by limiting design time and “figuring it out in the field.” Those “cost savings” will erode quickly once construction commences.

If you can find a builder who will offer a fixed-price bid, check out their operation. They don’t have to match our setup and our process, but they should have the essential elements. Learn about their process, check references, and look at other houses they’ve built. Every year, projects around the country blow past estimates and fall behind schedule, especially after clients select the low bidder. Great builders will tell you what you may not want to hear, but need to, early in the process.

As soon as you find the right builder, get them involved to start giving budget guidance, to interact with design professionals on materials and methods, and to jointly troubleshoot tricky parts of the project. Establish this team early in the project design cycle.

Thoughts for builders

Most builders are eager to start construction and let the project evolve from there. But here is the dirty little secret: Every single one of these unknowns must—and will, at some point—become known. And each one that you bring in from the wild, before construction commences, is one fewer place where your project can get off track, affecting budget and schedule. Why not just make the decisions sooner?

Let’s be clear: We certainly don’t foresee a time when 100% of the work in our industry shifts to a fixed-price methodology like ours. Not everyone can budget home construction projects in this way.

What we hope is, by opening this dialogue, builders and clients alike will ponder if they would be significantly more satisfied by shifting more of their energy and resources to the preconstruction phase of their project, in lieu of construction. Would investing the appropriate time and fees required to wring ambiguity from the project produce a better journey and project? Are residential contractors across the country staffed with too many builders and not enough planners? Should we think twice and cut once?

I’m not sure we’ve found the holy grail. But we’re delivering projects of significance, on time and on budget, for happy people, and having lots of fun while doing it.

To read a PDF version of this article on how to budget home construction more effectively, click the View PDF button below.