A Hybrid Approach to Lime Plaster

Drywall backing speeds the way to a textured, durable, old-world finish.

Synopsis: While drywall has replaced plaster as the go-to material for walls and ceilings, it does not replace the look, feel, and durability of hand-applied plaster. Ace McArleton describes his approach to plastering, which involves using drywall as a base (primed with sand and glue) for lime plaster. The article describes the proportions of lime, sand, and water used to achieve a durable plaster that will trowel on easily, and then walks through the process of taping the walls followed by different techniques for using trowels to apply plaster to the field, around trim, and over outside corners. Watch the related video to see the process in action.

Traditional plastering is a slow, laborious process, so it’s no wonder that when drywall came on the scene, it quickly replaced plaster as the go-to material for walls and ceilings in American homes.

But while drywall replaced plaster in function, it doesn’t replicate the look, feel, and durability of hand-applied plaster. Unlike drywall, plaster is a truly custom finish that can be sculpted and troweled to any number of desired shapes and textures. One of my favorite types is lime plaster—a strong, environmentally friendly, beautiful finish that has been around for millennia.

Made of a mix of sand, lime, and water, lime plaster has a high index of refraction, giving surfaces a warm glow that subtly changes color and tone as the sun shifts. The textures created by the sand and the plasterer’s trowel work can add even more dimensions of interest.

By contrast, the flat, smooth finish that drywall is meant to achieve in much of the United States is, by design, one-dimensional. When texture is added, it often just mimics traditional plasters.

Still, we like drywall. It’s a key component of our hybrid plastering approach, which takes advantage of some of drywall’s efficiency, availability, and strength, and melds it with the beauty of true lime plaster. Depending on the details, complexity, and size of the project, this method of plastering runs from $5 to $9 per sq. ft. This approach is more labor intensive than standard drywalling, but not nearly so laborious and costly as a standard three-coat plastering process.

Drywall replaces lath

Drywall provides a solid base for lime plaster, and goes up faster than the wood lath of the recent past. The drywall is hung in standard fashion, but it doesn’t get taped, so we don’t worry as much about the number of seams and can use shorter drywall panels, which makes it easier to estimate and hang.

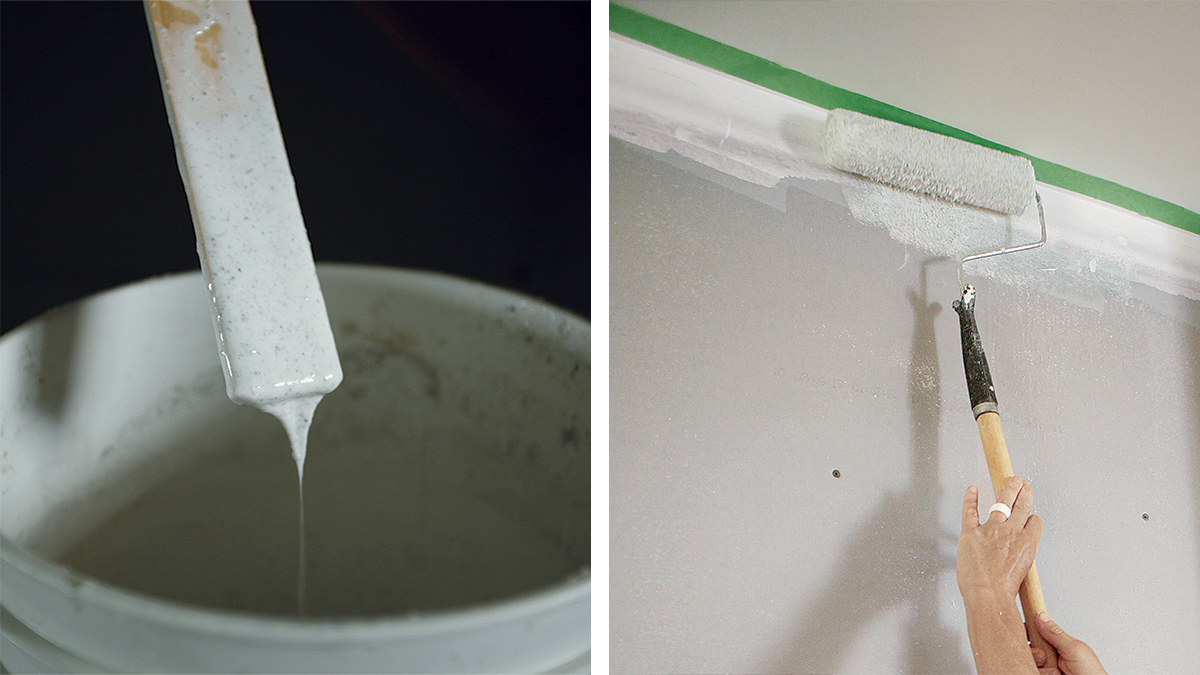

Typically we use standard drywall, which is designed to tolerate wetting from drywall compound and water-based paint, and tolerates wetting from lime plaster much the same. We prime the drywall with a mixture of sand and Elmer’s Glue-All (a PVA glue, which is similar to PVA-based primers). We roll and brush this slurry on just like paint to give the wall some tooth to help hold the plaster. We haven’t had issues with lime plaster failing on bare drywall, but taking this extra step is a cheap insurance policy, and it dries quickly.

On this job, the drywall contractor installed blueboard, which is made to serve as a base for veneer gypsum plasters. We’ve found that the extra expense of blueboard isn’t necessary, but it doesn’t hurt either.

The right mix is key

The lime plaster used here has two primary components: sand and hydrated lime. If you think about it like a brick wall, the sand is the brick, which provides the structure, and the lime is the mortar that holds it together. The sand needs to be sharp and clean and have a variety of grain sizes, but none any larger than about one-fifth the thickness of the plaster layer. Larger grain sizes give the plaster a coarser texture; for smoother finishes, use finer sand.

For finish plasters, we typically use limestone sand because its light color creates a bright plaster, and Type S mason’s lime, which is commonly found in 50-lb. bags from local building supply yards. Ask for the freshest bags—the longer the product might have been exposed to moisture and air, the less active the contents will be.

Getting the proportions of lime, sand, and water just right is critical to creating a durable plaster that will trowel on easily. For this process, the lime to sand ratio shouldn’t be more than 1:2, or less than 1:4. The mix used here is one part Type S mason’s lime to three parts sand. Add water a little at a time until the plaster can be formed into a ball that doesn’t fall apart when tossed, and that sticks to the inside wall of a wheelbarrow when thrown against it.

It’s better to add too little water at first than too much—too much water will cause hairline cracks to form as the water evaporates and the plaster shrinks. The less water, the less shrinkage. Still, water is needed to activate the lime and make a workable plaster. After mixing, give the lime 24 hours to activate—keeping it covered—before applying the plaster.

Unlike cement stucco or gypsum plaster, hydrated lime plaster sets only when exposed to air, and will stay soft indefinitely if kept sealed from it. This is distinct from hydraulic lime, which will even set under water.

Hydrated lime hardens in two ways—first by drying, but more importantly by curing, during which the hydrated lime absorbs carbon dioxide from the air and recrystallizes into limestone. The process of making lime from limestone drives off carbon dioxide, but because CO2 is reabsorbed during the curing process, it’s a desirable material for green building.

Trowels and textures

Coats of lime plaster need to be thin to absorb enough carbon dioxide to cure properly. When plastering over drywall, we use a single coat that’s 1/4 in. to 1/2 in. thick. To aid in getting the thickness right, we use painter’s tape to set reference lines on the trim, ceilings, and windows. The tape serves as rudimentary screed lines, and protects adjacent surfaces from errant plaster.

The mechanics of getting plaster onto the wall and achieving the desired texture take practice, and would take volumes to explain, but there are some general guidelines. Lime plaster has a long open time, which can be stretched out by tempering the plaster on the wall with spritzes of water—but do this with caution. Too much water can weaken the plaster and cause cracking. It’s also important to not overwork the plaster, as the heat and friction generated by troweling can also weaken it.

Rectangular plaster trowels and round-edged pool trowels are best for getting lime plaster onto the field of walls and moving it around. Both of these tools are large and can load and smooth large amounts of material with each stroke. For small areas, corners, and returns, use a small pointing trowel or margin trowel to get the plaster in just the right spot.

Start plastering at the top of an inside or outside corner, and use the tape screed line on the ceiling to establish the thickness of the plaster. Starting at the top and working down is crucial to preventing dropped plaster from marring the work you’ve already done.

Don’t worry about getting the surface flat right away; it’s more important to get enough material on the wall to be able to move it around. After getting enough plaster on the wall to cover about 10 sq. ft., use large trowels and bodyweight to trowel it to the right thickness. Once that’s established, use the edge of that section as a reference to extend the field of plaster across the top half of the wall. Before moving to the bottom of the wall, trowel the plaster flat with a pool trowel. As it hardens, it gets harder to smooth.

The plaster will be leather-hard in about four hours, and takes three to seven days to cure. Because it needs some water to cure, it may be necessary to occasionally spritz the walls with water, but tarping the walls with fabric or plastic isn’t necessary for indoor applications.

For more on Lime Plaster:

- VIDEO: Lime-Plaster Installation Over Drywall

- A Short Guide to Lime-Plaster Trowels

- Add Color to Lime-Plaster Walls

- From Rock to Dust to Rock Again: An In-Depth Look at Hydrated Lime

- Lime-Plaster Transformation: A Slideshow

To view the article as a PDF, please click the View PDF button below.

View Comments

My first, built in late 1941, and my third and current home, built in 1954, used drywall button board as "lath" and then were covered in smooth plaster on all interior wall and ceiling surfaces.

My second home, built in 1951, used standard drywall with a skim coat applied in a manner that mimicked a randomly textured plaster wall on all interior wall and ceiling surfaces.