The (Often Painful) Evolution of Residential Fire Sprinklers

Get an understanding of 3 unique sprinkler systems designed to meet building codes, to maintain healthy domestic water, and ultimately to help save lives.

When the 2006 International Residential Code (IRC) debuted a design method for single-family-home fire sprinklers that utilized the potable-water plumbing system to supply the heads, it was in the appendix, not mandatory, and thus received little attention. But in the following edition (2009), it moved to the main body of the IRC and became a requirement. Since then, there’s been controversy, appeals, state legislation, and three more editions of the IRC that have maintained the requirement (2012, 2015, 2018).

As of this writing, only California, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., have adopted statewide sprinkler requirements. In fact, 31 states have adopted quite the opposite—legislation prohibiting state or local sprinkler provisions. The remaining 17 states allow local governments to adopt the provisions, and there you will find assorted locations where they are required. I worked in one of those locations and have therefore helped to administer mandatory sprinkler requirements for over six years.

I have come to understand the resistance and delay to enacting sprinkler requirements. It’s not easy for builders or code officials. On the one hand, though, it should be easy. We have been using fire-sprinkler systems for decades in public spaces. On the other hand, a single-family home isn’t a public space, which makes oversight more difficult.

Over the course of those years, I worked with local home builders as they tried to satisfy the code requirement, stay profitable, and keep their customers—the homebuyers—happy. With every approach to providing sprinklers, we were faced with new and unexpected results. With every solution came a new problem.

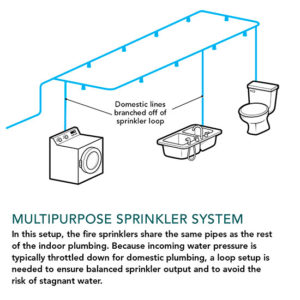

Multipurpose systems

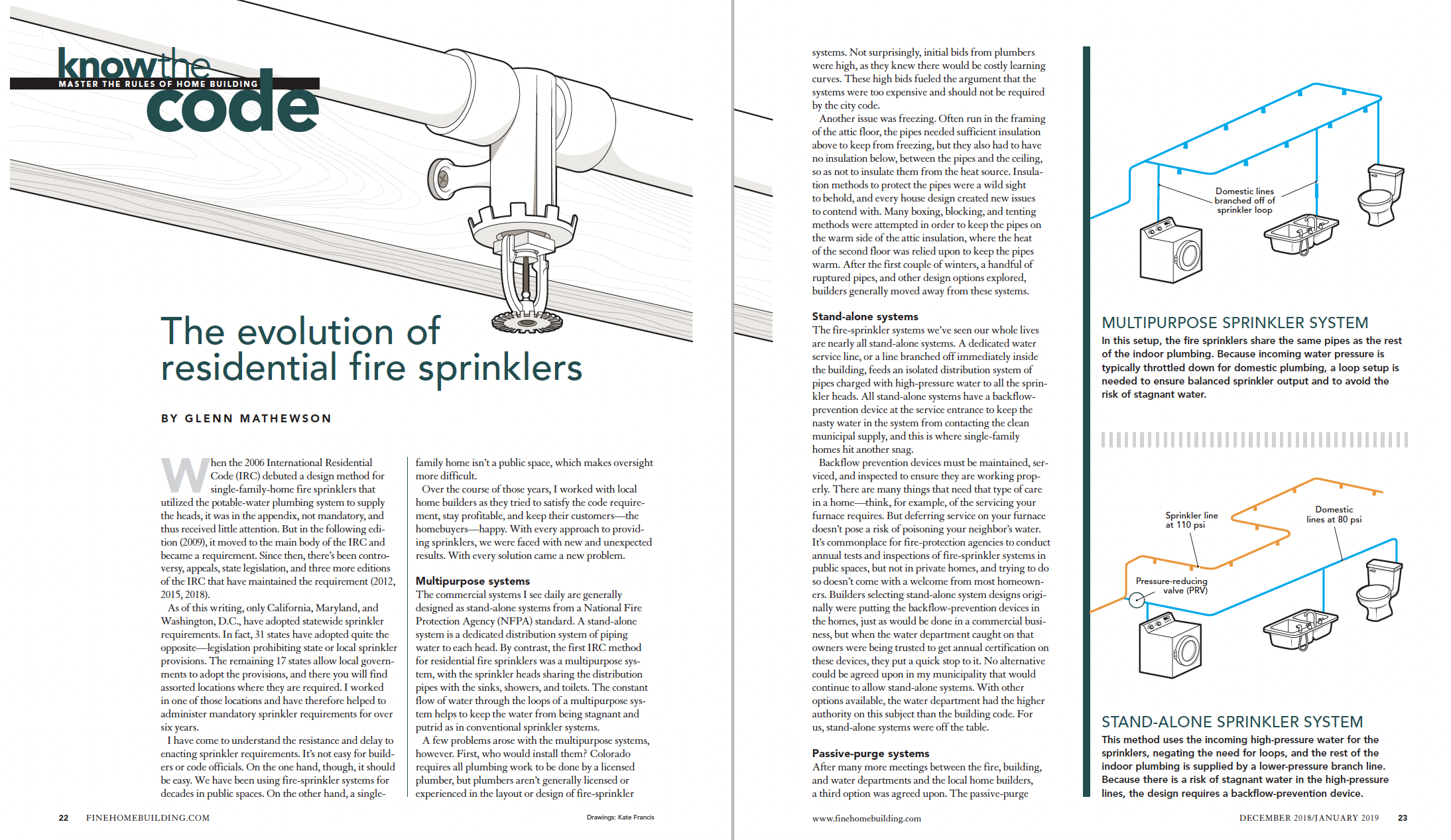

The commercial systems I see daily are generally designed as stand-alone systems from a National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) standard. A stand-alone system is a dedicated distribution system of piping water to each head. By contrast, the first IRC method for residential fire sprinklers was a multipurpose system, with the sprinkler heads sharing the distribution pipes with the sinks, showers, and toilets. The constant flow of water through the loops of a multipurpose system helps to keep the water from being stagnant and putrid as in conventional sprinkler systems.

The commercial systems I see daily are generally designed as stand-alone systems from a National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) standard. A stand-alone system is a dedicated distribution system of piping water to each head. By contrast, the first IRC method for residential fire sprinklers was a multipurpose system, with the sprinkler heads sharing the distribution pipes with the sinks, showers, and toilets. The constant flow of water through the loops of a multipurpose system helps to keep the water from being stagnant and putrid as in conventional sprinkler systems.

A few problems arose with the multipurpose systems, however. First, who would install them? Colorado requires all plumbing work to be done by a licensed plumber, but plumbers aren’t generally licensed or experienced in the layout or design of fire-sprinkler systems. Not surprisingly, initial bids from plumbers were high, as they knew there would be costly learning curves. These high bids fueled the argument that the systems were too expensive and should not be required by the city code.

Another issue was freezing. Often run in the framing of the attic floor, the pipes needed sufficient insulation above to keep from freezing, but they also had to have no insulation below, between the pipes and the ceiling, so as not to insulate them from the heat source. Insulation methods to protect the pipes were a wild sight to behold, and every house design created new issues to contend with. Many boxing, blocking, and tenting methods were attempted in order to keep the pipes on the warm side of the attic insulation, where the heat of the second floor was relied upon to keep the pipes warm. After the first couple of winters, a handful of ruptured pipes, and other design options explored, builders generally moved away from these systems.

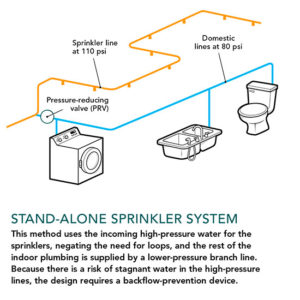

Stand-alone systems

The fire-sprinkler systems we’ve seen our whole lives are nearly all stand-alone systems. A dedicated water service line, or a line branched off immediately inside the building, feeds an isolated distribution system of pipes charged with high-pressure water to all the sprinkler heads. All stand-alone systems have a backflow-prevention device at the service entrance to keep the nasty water in the system from contacting the clean municipal supply, and this is where single-family homes hit another snag.

The fire-sprinkler systems we’ve seen our whole lives are nearly all stand-alone systems. A dedicated water service line, or a line branched off immediately inside the building, feeds an isolated distribution system of pipes charged with high-pressure water to all the sprinkler heads. All stand-alone systems have a backflow-prevention device at the service entrance to keep the nasty water in the system from contacting the clean municipal supply, and this is where single-family homes hit another snag.

Backflow prevention devices must be maintained, serviced, and inspected to ensure they are working properly. There are many things that need that type of care in a home—think, for example, of the servicing your furnace requires. But deferring service on your furnace doesn’t pose a risk of poisoning your neighbor’s water. It’s commonplace for fire-protection agencies to conduct annual tests and inspections of fire-sprinkler systems in public spaces, but not in private homes, and trying to do so doesn’t come with a welcome from most homeowners. Builders selecting stand-alone system designs originally were putting the backflow-prevention devices in the homes, just as would be done in a commercial business, but when the water department caught on that owners were being trusted to get annual certification on these devices, they put a quick stop to it. No alternative could be agreed upon in my municipality that would continue to allow stand-alone systems. With other options available, the water department had the higher authority on this subject than the building code. For us, stand-alone systems were off the table.

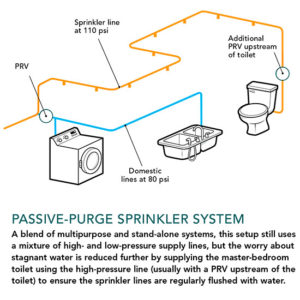

Passive-purge systems

After many more meetings between the fire, building, and water departments and the local home builders, a third option was agreed upon. The passive-purge design from the NFPA is a mix of the multipurpose and stand-alone designs. It branches separately after the water service enters the home, but it also supplies water to the master-bedroom toilet or sometimes the farthest toilet in the system. The assumption is that this toilet will be flushed regularly, and the rush of water headed to the toilet is supposed to create enough movement in the system to keep the water from going putrid.

After many more meetings between the fire, building, and water departments and the local home builders, a third option was agreed upon. The passive-purge design from the NFPA is a mix of the multipurpose and stand-alone designs. It branches separately after the water service enters the home, but it also supplies water to the master-bedroom toilet or sometimes the farthest toilet in the system. The assumption is that this toilet will be flushed regularly, and the rush of water headed to the toilet is supposed to create enough movement in the system to keep the water from going putrid.

Everyone believed that this plan would work and that it would keep the potable-water system safe—except the water department. As a compromise, the department requested a check valve in the sprinkler system as a backup solution to protect the domestic water if the passive-purge system didn’t work. The city would then provide a legitimate backflow-prevention device in the meter pit outside the home and would take responsibility for having it certified annually.

While this passive-purge system has become our go-to method, it still has its problems. First, new homeowners who did not fully read the conditions of their purchase were unhappily surprised a year later to discover an additional line item in their water bill for “backflow-prevention device certification.”

Second, passive-purge systems take their water prior to the pressure-reducing valve (PRV) that protects the domestic system from pressures above 80 psi. This allows the fire-sprinkler system to use the higher municipal pressures, often 120 psi or greater, and eliminate the need for loops in the attic. Second-floor heads can be run individually and vertically up each wall and can utilize wall-mounted heads. This effectively keeps water lines out of the attic for nearly all home designs encountered. But there is still that one toilet hooked up to a high-pressure supply line. After enough complaints about toilets making a hissing noise due to the high-pressure water running through the fill valves, builders began installing a second PRV just after the shut-off valve of these toilets.

Currently, the passive-purge systems appear to be working out for everyone, but only time will tell if these systems and the use of a check valve will indeed keep the water clean and/or the owners protected. The other methods are still allowed by code, but this implementation experience is a good reminder that nothing is an island. The building code must also work with water quality, engineering, fire protection, and many other professionals to make any system in the built environment work as expected.

Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with buildingcodecollege.com.

More from FineHomebuilding.com:

- Fire Sprinklers: Coming to a Home Near You

- Danger Can Be a State of Mind

- What You Didn’t Know About Alarms

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below:

View Comments

Are there methods of installing sprinklers appropriate for those of us with private wells?

This isn't a direct answer to the question about private wells, but about 25 years ago I designed a house for a builder for his own home on a site about 20 miles outside of Seattle, overlooking the Snoqualmie River valley. Sprinklers were required because the fire department determined that the access to the site was not adequate for their vehicles. The house was completed in the winter and the inspector required the builder to prove that he had the water flow from his well to meet the requirements for the sprinkler system. The results of the successful test was a huge sheet of ice. So it would seem that yes, you can use a private well but you might have to prove that it provides enough water for the sprinkler system.

Definitely a hot topic! Strong work Glenn!

https://www.aricgitomerarchitect.com/hot-topic-home-fire-sprinkler-systems/