Revolutionary Remodel

Architect Robert Gurney reshapes history at 308 Mulberry Street.

Just because the starting point is a historical house doesn’t mean you have to end up with a project that is a slave to revivalist architecture. —Robert M. Gurney, FAIA

When Robert Gurney Architect was called in to restore a 19th-century cedar-shingled house in the heart of the historic district of Lewes, Del., the team was prepared to get creative. The client loved the old house and its location, but he was looking for more—much more. Among his requirements: a large great room housing a kitchen, dining area, and living room; a workout room; a screened porch; and an outdoor shower. He also envisioned a swimming pool at the center of it all. That meant doubling the existing structure’s footprint.

To start, several prior additions at the back of the house were razed; they included a poorly proportioned living space, a shed-roofed screened porch, and a storage room. “I wanted the historical building to remain the most important element of the project,” Gurney explains, noting that getting rid of all but the small original structure helped to accomplish that. So did the deep research that informed its wholly accurate restoration—right down to the number of windowpane lites and the section of standing-seam roof.

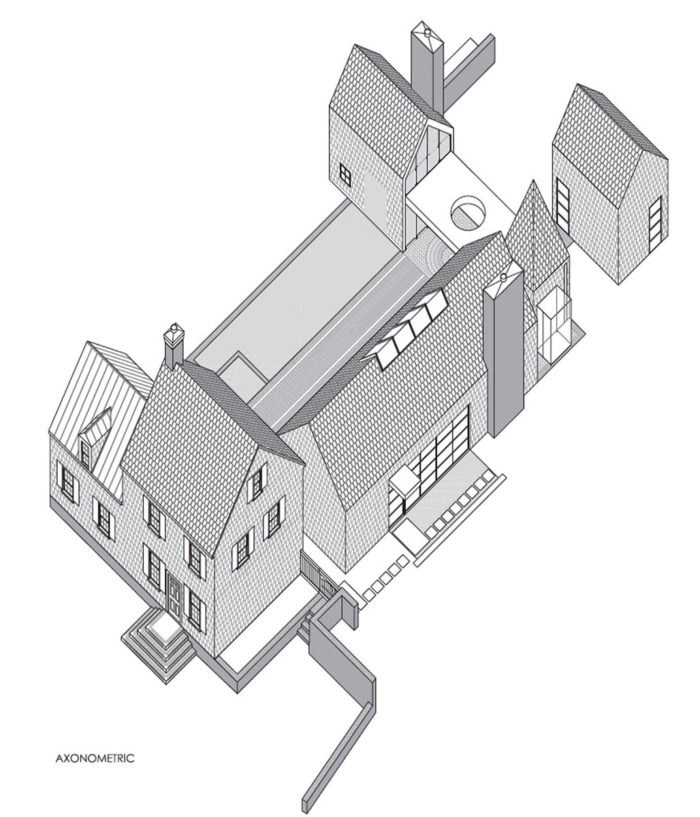

Far from a nostalgic iteration of a bygone era, the house at 308 Mulberry Street is a study in contrasts. It is at once a respectful homage to the timber homes that characterize the neighborhood and an unlikely take on modern design. Rather than doing the “seamless addition thing” or, conversely, tacking on a contrary structure to the rear of the existing house, Gurney settled on a design that would allow the historical home to shine among the desired additional spaces, which took the form of a series of interconnected one-story pavilions organized around the pool and a cherished old deodar cedar tree. Taken together, they form a kind of compound.

This breaking up of large masses to define living spaces in a single volume is something Gurney values. “Rather than putting everything under one big roof, [this approach] makes the house a collection of smaller parts. Doing that results in more interesting masses and spaces, plus we are creating more wall space, which means there are additional opportunities for windows and different orientations for bringing in light.” The great room, with its walls of glass and long skylight at the ridge, is a prime example of such a space.

With its period-appropriate exterior detailing, the original two-story house does indeed take a prominent position in the composition of structures. It houses the main entry and four bedrooms, while all other rooms are found in the generously proportioned, light-filled pavilions. Moving away from tradition, the main-house walls are devoid of trim, casings, moldings, and baseboard. Instead, interiors feature a floating staircase, glass walls, stainless steel, and aluminum. In the new buildings, materials—such as the mahogany used for the wall and ceiling paneling of the great room and the Douglas fir used inside the screened porch and workout room—are heavily weighted. This contrasts with the main house, where interiors are kept stark-white and simple. “There was this juxtaposition—everything that was new had a really rich interior, but in the old building the idea was to let the massing of the house be the most important thing,” Gurney explains.

The gable roofs found on the pavilions relate directly to the original house. “We wanted to continue that language in terms of the massing as well as the exterior materials,” says Gurney, noting that the new buildings depart from tradition where overhangs and fascia boards were omitted. They are instead distinguished by crisp edges. Similarly, continuing materials from wall to roof on the exterior and wall to ceiling inside is a more modern treatment that accentuates clean lines over ornamental trim and moldings.

Another design decision worth noting is the extensive use of red brick, which speaks to the regional vernacular and is seen in the garden walls, entry steps, sidewalk, and chimneys, lending both horizontal and vertical visual interest.

On the whole, this project demonstrates that it is possible for modern architecture to adopt and even celebrate timeless aspects of traditional forms and materials. Or, as Gurney puts it: “I believe a modern architectural language can comfortably coexist with [period architecture]. I think the strong points of each magnify the benefits of the other.” Fortunately, the Lewes Historical Preservation Commission agreed.

Photos by Maxwell MacKenzie, courtesy of Robert Gurney Architect

For more historic home remodels:

- Modernizing Traditional Homes

- Restoring an Antique Timber-Frame Home

- Modern Techniques Restore a Historic House

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

View Comments

fantastic design