Architectural Archeology Informs the Restoration of a Centuries-Old Farmhouse

The Thomas Massey House illustrates the lengths to which architect John Milner goes to preserve historical buildings.

“Archeological investigation is a very slow process, and it has to be done carefully—an errant swing of the hammer could destroy something important. It’s a matter of gently probing and subtracting things until you get to the level you are looking for.” —John Milner, FAIA

Architect John Milner specializes in the preservation and restoration of historic structures. Based in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, his firm honors past architects and artisans by unearthing building materials and construction methods from centuries long gone. Conducting what he calls “archeological investigations,” Milner completely restored the Thomas Massey House, which is now a house museum with significant interpretative value.

During his 37-year tenure as adjunct professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, Milner taught a course called Architectural Archeology, for which there was no textbook. Instead, he would take students to a historic building, where they would spend a semester sleuthing. The objective was to discover how the structure was built and what it would have looked like in its original form. “It’s aboveground archeology,” says Milner. “You dig around in the building to figure out how it changed over time.”

Skillfully removing all but the original structure and materials, Milner and his students would uncover a building’s physical and cultural history. Their work included scientific techniques such as GPR profiles (geophysical subsurface investigations whereby radar waves are directed into the ground to determine anomalies) and microscopic paint, finish, and wallpaper analyses. Historic framing methods, window and door construction, molding treatments, mantel profiles, plaster types, nail chronology, and the evolution of fireplaces are just a few of the subjects studied during such projects.

This building was constructed in four phases, spanning as many decades. The original house—most likely a small wood-framed structure that is no longer in existence—was built sometime prior to 1696, when an addition was put on. Then, in the 1730s, the original structure was torn down and a stone section was built. That, in turn, was expanded in the early 19th century to include a stone-walled kitchen, and in 1860, a second story was added above the kitchen.

By the time John Milner Architects was called upon, the building had been neglected for decades. Milner’s team was charged with restoring each section to its respective period. His investigations revealed a number of significant features, including a walk-in-fireplace and beehive oven, leaded-glass casement sash in walnut frames, and a stenciled staircase. In the 1696 section, he found intact the original summer beam; the poplar and walnut floor framing system for the first, second, and third floors; and even some of the original plaster.

The 1730s portion contained painted woodwork. With it they were able to conduct a microscopic analysis to determine the original colors, which were then reproduced. The parlor was a pumpkin hue, the chair rail was painted a deep brown—perhaps to imitate the look of walnut—and persimmon was used for the interior of the china cabinet.

The last section of the building included a large cooking fireplace. “As these buildings expanded, the fireplaces were modernized,” Milner explains. “I’m sure the original wood house had a cooking fireplace, but when the addition was built, the owners either kept the cooking fireplace or they built a new one. Then it was moved into the next addition, and they filled in the previous cooking fireplace with a smaller parlor fireplace.”

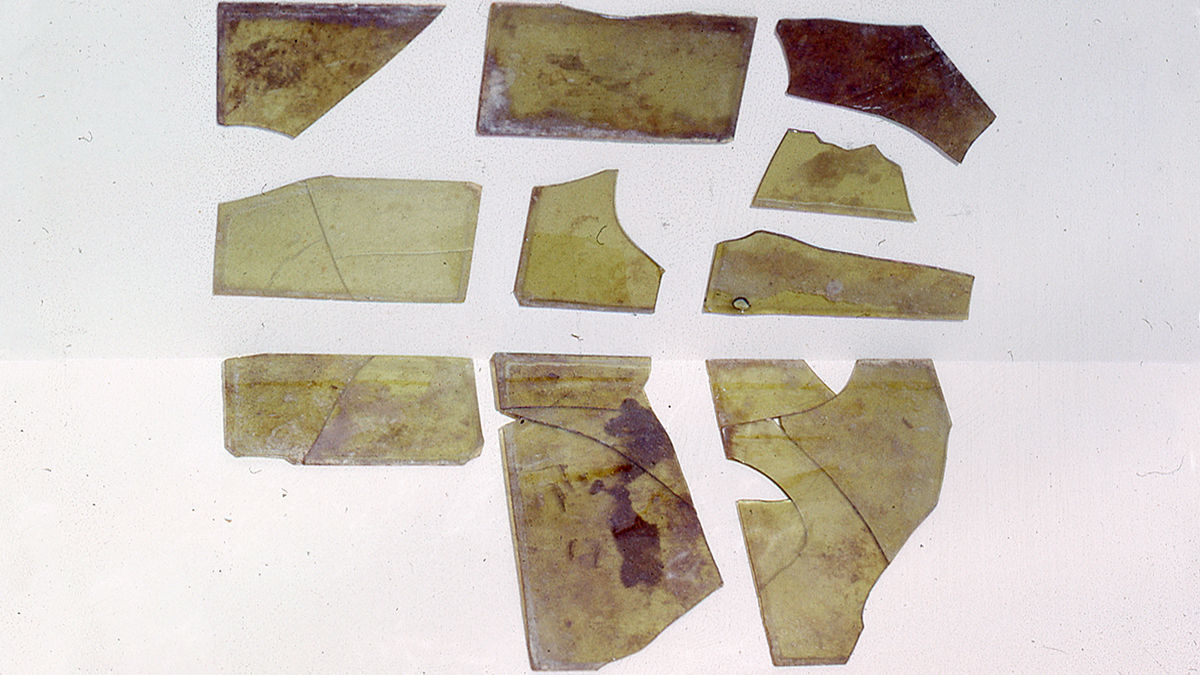

According to Milner, restoring the leaded-glass casement windows was particularly fascinating because they had been modified and turned into double-hung windows. He found pieces of original glass and lead cames, which, he says, “tied together a wonderful history of the windows.” And because they had so much information, they were able to reconstruct the original windows.

Today the building is fully restored and functional. As a house museum, it offers visitors a deeply authentic experience. “Because we were able to preserve so much of the original material from the 1690s, 1720s, and 19th century, you can walk through the house and see the different time periods represented by the materials,” notes Milner.

Photos by Geoffrey Gross, courtesy of John Milner Architects

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

All New Bathroom Ideas that Work

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

All New Kitchen Ideas that Work

View Comments

AWESOME Structure of this Fine Homebuilding

Happy to hear you enjoyed learning about this house.

Thanks for a great article! I grew up near The Massey House and have some great memories from family events we had there. I live in FL now, but took the family back home last fall and stopped in to say hi. Some great info on the history of the house is here: https://hsp.org/blogs/archival-adventures-in-small-repositories/marples-1696-thomas-massey-house

All the best,

Jonathan