A Manifold Model

Four years after its completion, the internationally recognized Taft House remains a leading-edge example of building science success.

In 2015, the Taft School, a private co-ed high school located in Watertown, Conn., brought in a design-build team to create a single-family house for faculty. The primary objective was for it to perform at the highest level of energy efficiency. Toward that end, the 2400-sq.-ft. two-story house was designed to surpass Passive House standards. So successful was the effort that not only did they achieve Passive House certification, but the house is also LEED Platinum and WaterSense certified; it also earned three of the seven Living Building Challenge (LBC) petals. Furthermore, it was the USGBC’s 2016 Best Single-Family House, and it earned the status of Best Energy Efficient House in the United States from the U.S. Department of Energy. Trillium Architects principal Elizabeth DiSalvo, who helmed the project, even traveled to the 2016 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Morocco, where it was the only American project honored. Simply put, it is—and remains—one of the world’s most energy-efficient houses.

In addition to Trillium Architects, the team included Steven Winter Associates and BPC Green Builders—the trio has been designing and building green homes together for more than 15 years. During each phase of this project they brainstormed ideas for making an “even better” house. “For every project we ask what can be done differently. We like to try new things to push the boundaries,” says DiSalvo, noting that they had already designed a few LEED homes and were geared up for Passive House certification. “We had done net zero and were just steps away from Passive House on our previous projects, so we wanted to go for it,” DiSalvo recalls.

The team also chose this project for their inaugural foray into the Living Building Challenge—the world’s most rigorous sustainable design framework and certification program, which is measured in “petals,” a reference to the idea that “the ideal built environment should function as cleanly and efficiently as a flower.” Though not part of the original plan, LBC certification gained favor with Taft faculty, staff, and board members who saw its potential as a teaching tool for engaging students. Initially, the need to demo an existing structure made the design team think that certification wouln’t be attainable, but they soon came around to making it a goal. “We realized we could come up with three petals,” says DiSalvo. “It was exciting to go for it—you don’t often have a client who wants to or can afford to do so many certifications.”

The Passive House certification program is focused strictly on energy efficiency, but DiSalvo is interested in a wider spectrum of performance standards, including health and well-being and embodied carbon. Striving for multiple certifications was a way to approach the house holistically, she explains. “LEED is good because it addresses all kinds of things—and then LBC takes it another step further,” she says. “I’m always happy to do LEED on a house. It gets everyone thinking about everything, not just energy. And you can’t change things midproject—you have to keep checking all of those boxes, which keeps you true. Plus, everyone learns something from each decision.”

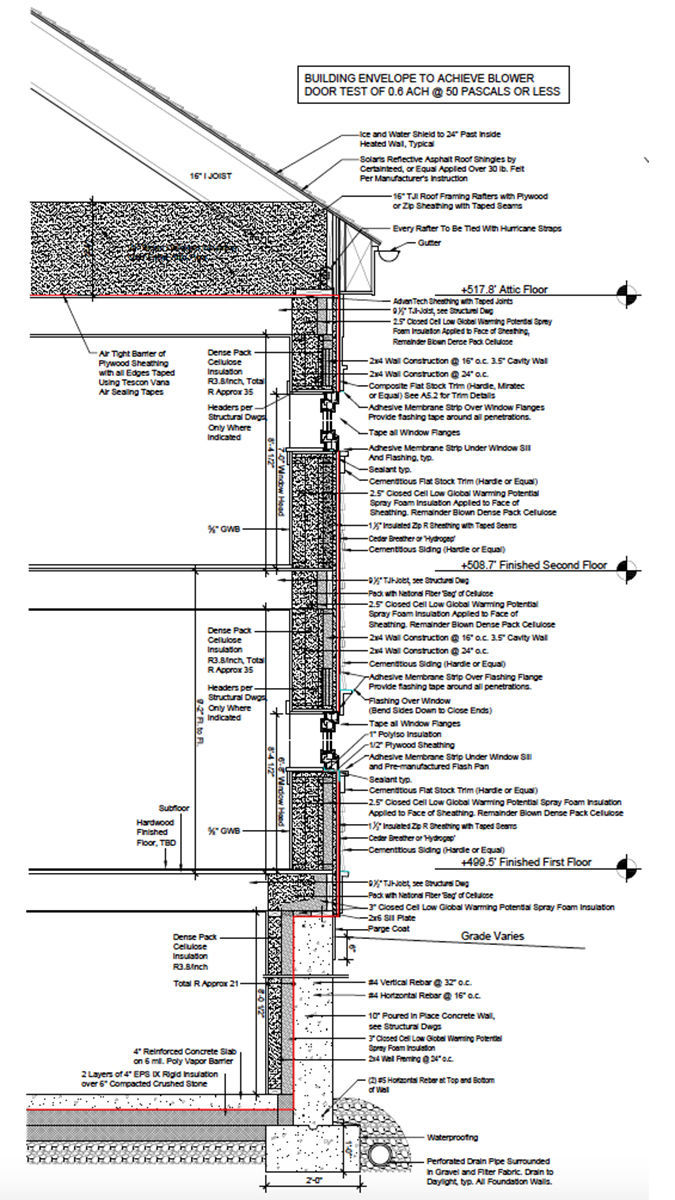

The Taft House is modeled after one of the first-ever LEED for Homes certified projects, which DiSalvo designed in 2009. It features 10.5-in.-thick double-stud walls insulated with closed-cell foam and dense-pack cellulose insulation, wrapped in Zip System R-sheathing for a 47.95 R-value. The unconditioned attic is filled with 24 in. of cellulose at the joists for R-84. Two layers of 4-in. foam at the foundation pad provide R-40, windows are R-7.5, and blower-door test results measured 0.45 ACH50. The builder designed the HVAC system, which is a combination of minisplits and a Zender ERV. He determined the proper refrigerant charge, verified thermostat control for each indoor unit, and ensured that all indoor units communicate with the single outdoor minisplit. He also adjusted the ventilation-system controls and remotes to be in accordance with the house size and number of bathrooms.

The house uses a lot less energy than was projected. “Sometimes it makes twice as much energy as it uses,” notes DiSalvo. “Part of the reason for that is that the occupants are very conscientious, but also, when we were building, we found ways—such as open-corner framing—to add more insulation, which meant not as much PV was really needed.” In addition to the supremely airtight envelope, the layout played a part in the production of surplus energy. “We kept everything tight to the core. It’s basically a doughnut of space around a core of plumbing and mechanicals, so all the runs and ducts are super short.”

Arguably the most challenging aspect of the project was meeting the historic commission’s specifications. It required the house to have historically accurate rooflines, windows, street orientation, symmetry, and proportions. The Greek Revival form solved much of the puzzle. “The classic Greek Revival is actually the perfect form because it’s tall and boxy, which is ideal for an energy-efficient house because you want to have as little envelope as possible to the interior space,” DiSalvo explains.

Period-appropriate windows are double-hung, but true double-hung windows can’t be manufactured with a U-factor that meets Passive House standards. The solution was to add an awning over a fixed window configuration that mimics the look of a double-hung. The window that needed to provide egress includes a casement with a thick check rail as a compromise. Window sizes were dictated, in part, by street orientation. Maintaining the classic order, windows on the east-facing facade are smaller than those on the west-facing backside, which is not visible from the street. On the north side, they placed as few windows as possible. Scale was kept in check by designing the rear of the house to appear as a later addition.

Were they to take on the same project today, DiSalvo believes they would omit all foam as well as the Zip R-sheathing. “The more you learn about foam, the more you don’t want to use it . . . and we could probably get the same R-values without it.” Additionally, they would use far fewer solar panels.

On a 2017 tour of the house, the occupants reported loving it—commenting on how quiet it is and how the air temperature is always perfect.

Photos courtesy of Trillium Architects

For more energy-efficient homes:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Musings of an Energy Nerd: Toward an Energy-Efficient Home

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate