Pocket Neighbors Create Community

Architect Ross Chapin explains the benefits and opportunities inherent in these occupant-friendly neighborhoods.

“Pocket neighborhoods are a great concept and already popular, especially among adults seeking greater energy efficiencies in their homes and more intimate community living and support systems.” —Mark Roth, developer

Here at Fine Homebuilding, we focus on the how-to of building houses because that’s the information our readers want. But my role requires me to think about the design plans behind the sawdust. I tend to consider one project at a time but a recently developed article introducing the 2019 FHB House—now underway in Kentucky’s Norton Commons—got me thinking more broadly, specifically about houses designed for whole communities rather than individual occupants. A Google search led me straight to architect Ross Chapin, author of Pocket Neighborhoods (Taunton Press, 2012).

Based in Langley, Wash., Ross Chapin Architects specializes in innovative neighborhood design, most notably what he termed “pocket neighborhoods” back in the mid 1990s. The idea evolved in response to a few trends Ross was seeing at the time (and still sees today). The first is the negative repercussions of disjointed neighborhoods at odds with the concept of community. “Suburban and small-town zoning is a setup for garage-fronted houses on wide, empty streets— leaving many of us isolated and disconnected,” he says. “That’s working against what we naturally want, which is social connection.” Second, he points to the fact that over 60% of the housing stock in most communities has just one or two occupants—yet the primary housing option is a family-size stand-alone house.

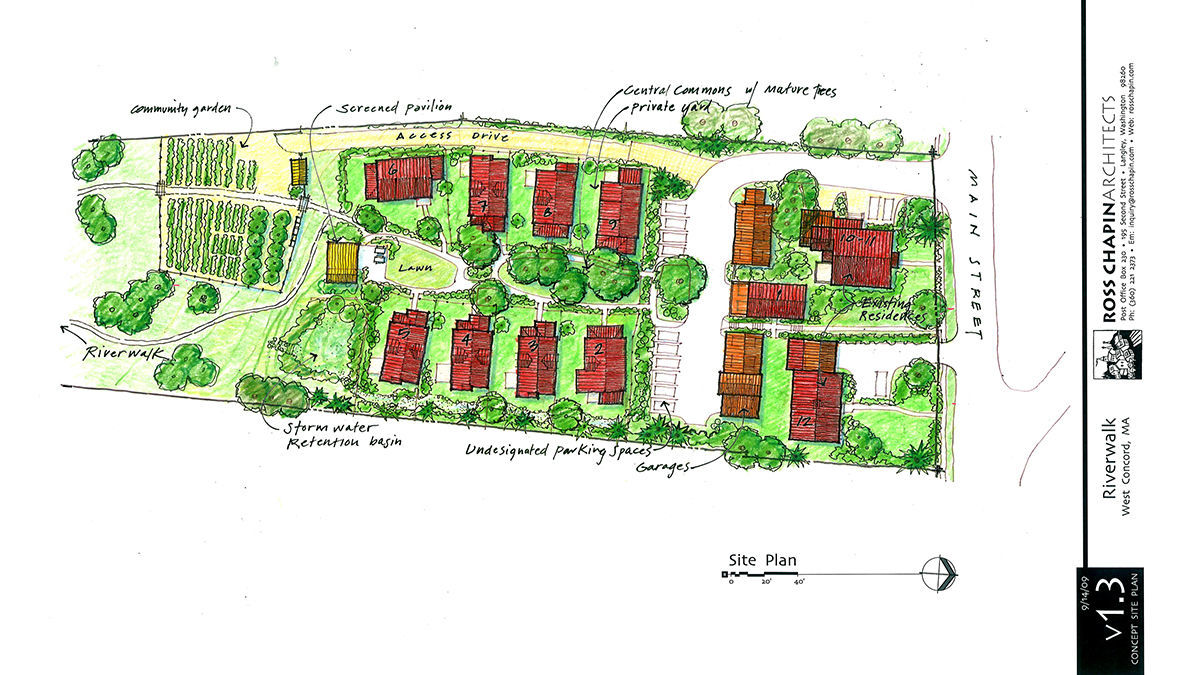

What defines a pocket neighborhood, in large part, is its orientation around a common space, whether it be a courtyard, pavilion, community garden, picnic area, or the like—anyplace that encourages social engagement. “Shared space is the heart of a pocket neighborhood,” says Ross. “It’s what holds it together and what gives it vitality.” Though his portfolio of projects illustrates the concept at varying scales, Ross says the ideal pocket neighborhood is comprised of 8 to 16 households—sometimes clustered into a few groups—located within a larger neighborhood context.

He describes such houses as being “nested” among one another. When homes are so closely spaced, it’s important to provide privacy. To that end, he designs houses to have an “open side” and a “closed side” so they can be comfortably tucked together. There are intentionally no windows looking into a neighboring house. Using structure and landscape plantings he also creates “layers” of privacy, whereby there is a pleasant transition between one’s own home and active shared spaces.

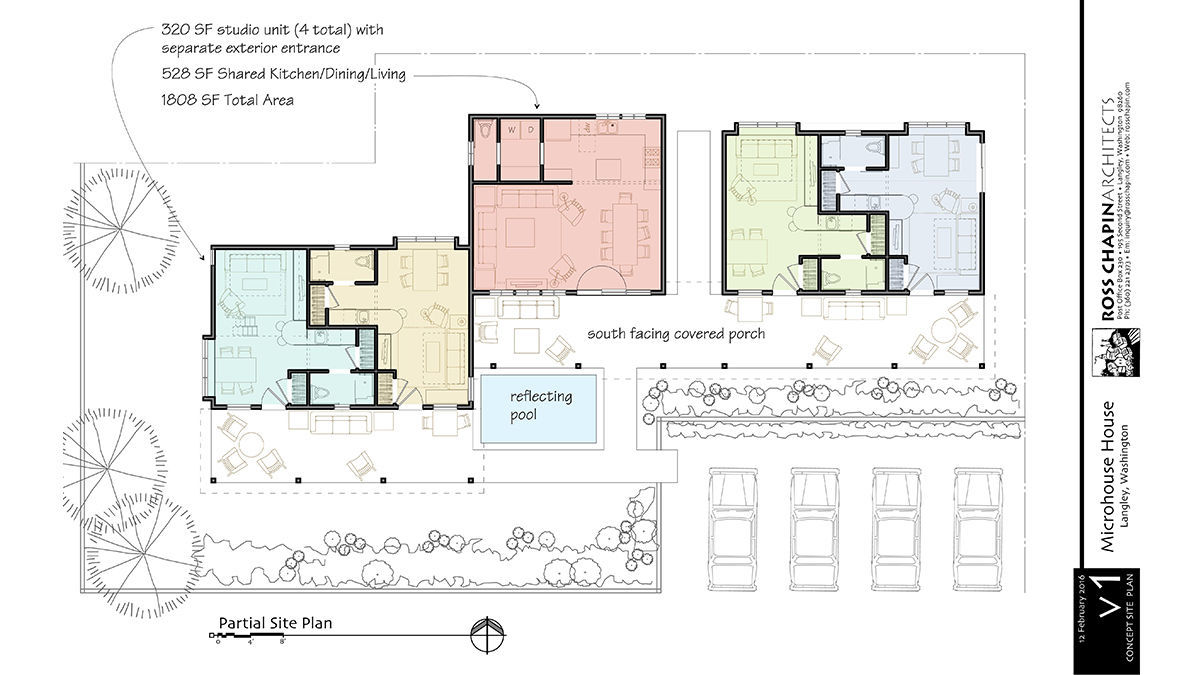

Ross has designed over 100 pocket neighborhoods—a few of which are still in the works. He has recently proposed an idea for a “micro-unit house” for seniors in Langley. In essence, it comprises four very small apartments tied together with a shared kitchen and dining room. Using the core floor plan of a conventional house, he found a way around code restrictions that wouldn’t allow multifamily or duplex housing. Ross explains: “A house is a house because it has a kitchen and it’s a kitchen because it has a stove. But an apartment or room without a stove is an accessory to the main house. There’s nothing to say you can’t have micro units—’bedrooms’—and shared spaces.”

The idea is to take tiny house living to the next level, and it has garnered enormous attention. He recently shared a blog post explaining what he has in mind. At last count, the post had 45K views and a large number of people from all over the country have expressed interest in seeing such a project built in their area. One couple, living in Skagway, AK, relies on seasonal employees who have a hard time finding short-term housing in the area. As a solution, Ross was hired to design nine living units in two houses on the couple’s double lot.

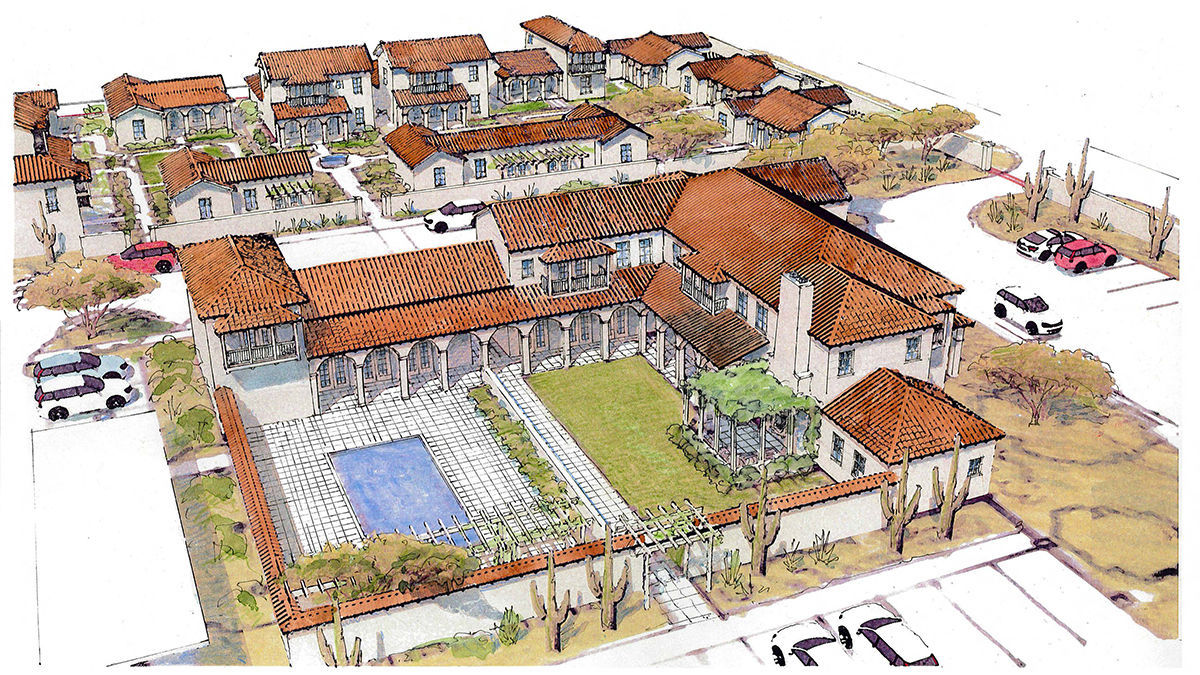

He has also received a hugely positive response to his idea for integrating people with special needs into pocket neighborhood communities. He notes that, when young, they have support in the form of school programs but help is harder to find when they reach adulthood and their support network is limited to aging parents. “We are trying to solve a need . . . and when the idea gets out, the response is electric,” says Ross. “There are people from every region of the country asking if we are going to build a special needs community near them.” In Phoenix, Ariz., he designed 30 households in two clusters organized around a common house. The challenge he faces is in accommodating a full range of incomes, which he views as key to success. “If you don’t have that, your community is not healthy.”

Pocket neighborhoods can take any number of forms. Consider, for example, the derelict property with 16 rental units that Ross, his wife, and another couple bought. He designed a central common house, converted the units into condos, and resold it for more affordable housing ($110K–$140K) in Langley, where houses typically start at $300K. It stands now as a diverse community of all ages and family types.

Existing neighborhoods can be made to function this way, too. Ross talks about “activating” your front yard with simple measures such as moving the picnic table forward, planting a vegetable garden, and removing fencing—all of which suggests a more neighborly attitude. In back, he recommends things like building a community garden, creating a play space for kids, or adding a shared pizza oven. “These kinds of things are doable with the people right around you for very little money,” Ross says.“It’s a matter of retrofitting community right where you live.”

There is also an underlying “green” side to this kind of design plan—though it is less quantifiable than the results of smart building science. For instance, these neighborhoods are highly walkable, which limits the need for trips by car, i.e. carbon emissions. Common ownership of goods and materials reduces consumerism, which carries embodied carbon—growing a community garden, for example, means fewer trips to the market to buy food shipped from hundreds miles away. Additionally, tight-knit, multigenerational communities have a kind of built-in service network, which saves on trips related to things like child and elder care. “You can’t underestimate the amount of energy saved by car trips not taken,” Ross notes.

Of course, Ross is mindful of new construction opportunities and he builds for energy efficiency and longevity. He designs climate-specific building envelopes and invests in high-performance HVAC systems. He also uses a few Passive House strategies. But he places equal, if not more, emphasis on the functionality and intrinsic green benefits of the neighborhoods he designs. “You go to all of the green building shows and read green journals and it’s all about building science, which is really key and I integrate it into everything I do, but in addition to that is something more about lifestyle.”

Perhaps the words that best make the case for pocket neighborhoods come from Ben Brown of PlaceMakers. Having once lived in a 308-sq.-ft. Katrina Cottage, he concludes: “The smaller the nest, the bigger the balancing need for community.”

If you have a project that might be of interest to our readers, please send a short description and images to [email protected].

Photos and drawings courtesy of Ross Chapin Architects

For more neighborhood planning:

View Comments

I can see so many potential problems with this concept. What if you don’t get along with your neighbor? What if your neighbor is a loud drunk? What if your neighbor insists on keeping 7 cats outside (this happened to me...), etc.

Homeowners Association, no doubt. Yes, john555. What if some of them are obnoxious or always want things done their way? Right now, I have 2 or 3 neighbors nearby and we rarely have problems. With this little community, there are a dozen families you have to interact with on a regular basis. Could be nice with the right group, but...

Just a way for developers to squeeze more people on a piece of land.