Built As Needed

Eric Moser’s evolution cottages are based on an incremental approach to building.

“Anything we design to be flexible must be able to respond to the climate and the local architecture as well as the context of the lot.”—Eric Moser

Eric Moser grew up as a farm boy in Indiana, where he developed a respect for tradition that continues to inform his work today. “Back then, people built what they needed at the time, with the expectation that it would grow,” says the principal of South Carolina–based Moser Design Group. “They were generational, permanent solutions as opposed to today, when we look at houses as throwaways.”

Eric’s portfolio includes what he calls evolution cottages, which began as a response to Hurricane Katrina. As part of the Mississippi Renewal Forum’s on-site architectural team charged with developing permanent alternatives to FEMA trailers, he helped identify the need for small, flexible houses or modules that could work in different contexts and on variable lot types. “The idea was to create a quick dwelling to get people back home as soon as possible,” Eric explains.

In time, the Moser Design Group designed a number of such building types but they added to the idea. Their evolution cottages are designed to adapt to new living patterns. Eric feels that the model of a single structure under one roof housing all living spaces and bedrooms isn’t one that best serves the majority of the population. He makes the point that the household dynamic has changed significantly over the last two to three decades, and that just 27% of households are married couples with children. “So many households now—both on the young end and the older end—are one or two individuals who may need living space for people who are not immediate family. We have the opportunity to make buildings that have a main house and a guest house, or that offer some kind of flexibility for control over how a household operates. You want to be able to put the puzzle together based on need.”

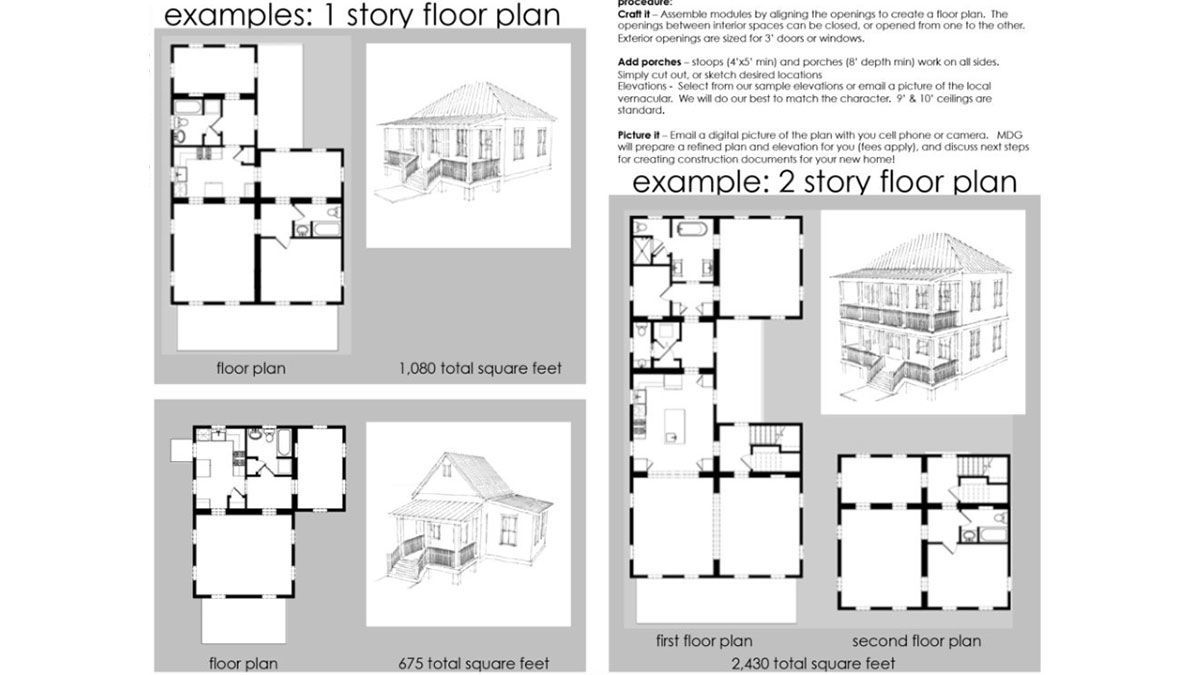

Evolution cottages are of two sizes: a single-story and a two-story. Both have a fixed envelope; how they are infilled is completely customizable. “The simplicity of the system is that all openings align so they can be plugged together almost like a Lego set,” says Eric. Core houses feature common living space and one or two bedrooms. From there, they can grow in any direction and also turn, which offers different frontage options. As occupants’ income levels and/or family sizes or dynamics shift, the house adapts. Rather than selling to move into a larger house or ripping off the roof for a second-story addition, new elements are added without being invasive to the main house. “We are going back to the way houses used to be built,” Eric explains, “when there was a main house and ancillary structures that would house separate rooms such as the kitchen. Over time, those buildings were connected.” The approach maintains the cottage scale and affords the opportunity to connect or add only when the need arises.

Eric notes the benefit of being in total control of how an ancillary space is used. “It can be an office, a rental unit, an in-home care room, or an apartment for an adult child,” he says. “It can do many things over the course of time, whereas in a conventional house, where you might have three bedrooms side-by-side, it’s harder to do that.”

The general floor plan for each of the two modules is wide and shallow, and they are designed to adapt to any site. On a rural lot they are likely to be front-loaded with a big porch facing the street; on a semi-urban lot, a stoop front and a rear porch make good sense. If intended for a tight urban lot, they can be turned to become side-court houses with a small street-front entry. Multiple orientation options allow houses to optimize views, sun paths, and ventilation.

Over the years, Eric and his team have worked to make the houses even more flexible. They are now detailed with fewer, more durable materials, and the components are sized for conventional or modular construction. They are also highly adaptable in terms of style. As his firm works internationally, he has locked down a design that accommodates a wide range of architectural elements—from vernacular to classical. “The homes can easily adapt to the regional appropriateness of a specific area and be re-skinned to allow Craftsman, Lowcountry, mountain, or mid-American detailing, to name a few,” Eric explains.

Storm preparedness is part of every build; windows are impact-rated for 35 mph and structures are tied down from the foundation to the roof ridge to withstand 130-mph winds. “We make sure the main roof forms are designed using best practices for uplift,” he notes, “and more often than not, our porches have sacrificial roofs—if they were to rip off, it wouldn’t necessarily breach the interior of the house.”

Eric shares his perspective on other building science strategies, saying: “Today’s houses have been coded to be completely isolated from their environment. You can’t even live in them without outside air intake because they are so tight—you literally can’t breathe very well in them. When you have a sealed environment like that, it acts like a space capsule, which means it takes just one pinprick to destroy the system.”

From the standpoint of efficiency and sustainability, Eric believes less is more and simpler is better. His approach is to minimize the number of materials that can get wet, hold water, and/or break. For him, that’s more sustainable than the multiple layers building science experts advocate. “We use old techniques to build structures that can withstand particular environments,” he says. “In America, we are so bound by building codes. And the code answer is almost always to add more layers, which means one more material that can fail. In our Caribbean projects, we make sure our houses are simple, like the oldest houses in America, which have survived because they can breathe.”

On a closing note, Eric mentions another strategy he uses: building smaller houses with bigger outdoor spaces. His idea is to entice people outdoors, which reduces the need for conditioned space. “More time outside helps people acclimate better to their climate, so they find they don’t need to turn the air conditioning on as much when indoors.”

Eric is clearly a designer who views houses and their surroundings as natural extensions of their occupants. It’s no surprise that the evolution cottage—designed to sustain a family over many generations—is his brainchild.

Photos courtesy of Moser Design Group

If you have a project that might be of interest to our readers, please send a short description and images to [email protected].

For more cottages:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

Musings of an Energy Nerd: Toward an Energy-Efficient Home

Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave