Retrofitting a Home Elevator

Powered by suction, pneumatic vacuum elevators are a low-maintenance, compact alternative to conventional lifts, plus they have a much more modern look.

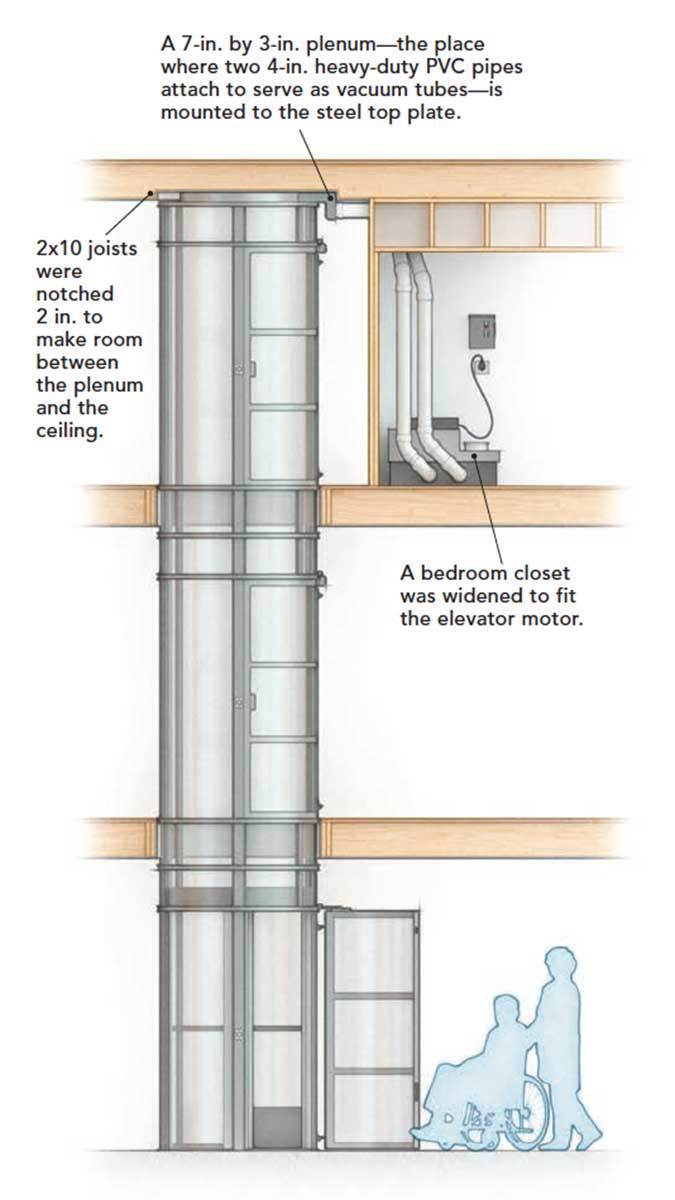

Synopsis: Pneumatic vacuum elevators operate on air pressure, and unlike conventional elevators, they don’t require a pit, shaft, or mechanical room so they take up less space. Design editor Kiley Jacques describes the process of installing an elevator from cutting the openings to installing the tubes and connecting the parts and explains how adding this level of accessibility can make it easier for homeowners to age in place.

An increasing number of people are outfitting their homes to support aging in place. According to the AARP, nearly 90% of seniors last polled reported wanting to stay in their own homes well into their golden years. In the majority of cases, that means changes need to be made; some minor, others more significant. Among the suggested home modifications to support mobility, safety, and independence are home elevators —a rising trend.

Finding a fit

For this project, the homeowners opted for a pneumatic vacuum elevator (PVE), appreciating its compact fit. Unlike conventional home elevators, PVEs do not need a pit, shaft, or mechanical room. After reviewing the options, they settled on Pneumatic Vacuum Elevators’ PVE52 model, which is designed to make two to five stops and carry up to three people or 525 lb.

When determining where to put it, the clients and architect Stephen Lasar talked about having the elevator come up from the garage into the main entry foyer—in that location, they wouldn’t have needed to build a lift from the garage to the basement floor. But there was a large air handler in the way, and a significant amount of ductwork would have needed moving. It could have been done, but the occupants nixed the idea because the tube would have been almost in the middle of the dining room. They also discussed putting it behind the garage, but that posed a number of structural complications. Ultimately, they decided to run it from the basement floor through the entry hall and to the second floor. A mechanical lift gets them from the garage to the elevator.

Cutting the openings

Before installation, builder Rob Riebe, owner of Riebe Construction Co., and his crew put in 350 hours of prep time. The team was charged with removing the wall between the dining area and entry hall, cutting into two floors to create 54-in.-diameter openings, and excavating for the mechanical lift—this last task proved especially challenging when they discovered a huge boulder in the way. On the second floor, the crew moved a wall to gain 9 in. in the hallway, which provides 4 in. of clearance where the elevator comes closest to the wall. It was above the second floor that they needed to add the hoisting support beam. A bathtub located on the third floor made it challenging to install that beam, which had to be supported with stacked studs down to the foundation.

Installing the tubes

When the preparation work was done, an installation team from Connecticut-based Elevator Service Company came to measure the critical dimensions—PVEs have to be within 1⁄8 in. When all was confirmed, they arrived in four vans with all parts on board. The first day was devoted to offloading and assembling the components. Once the cylinder panels were snapped together within the frame, the crew moved the elevator into the house in three sections, starting with the topmost head unit, which houses the turbines, valves, and control cabinet. Then, they hoisted the first- and second-floor sections to the proper levels and moved them aside. Next, they set the bottom section level and plumb and attached the steel pins that would connect it to the section above. A bead of silicone sealant was applied around the entire top of the tube, and a 16-in. connecting ring was inserted between the floors. This sequence was repeated for each section.

|

Hoisting in sections. A new support beam was added to the third-floor joists to carry the pulley system and loads as the tube is lifted into position. |

It took the four-member crew six days to finish the job—it was comparatively complex because of the two stops and tight squeeze on the second floor, plus the learning curve when working with this new type of elevator. After the homeowners’ long-anticipated inaugural ride, there was no doubt about the peace of mind their new PVE provides. With it in place, they foresee many mobile years ahead. “Making a home accessible is difficult and requires attention to detail,” Lasar says. “It is always good when one can combine accessibility and good design so that a person with a disability doesn’t feel second-class.”

How PVEs work

Kiley Jacques is design editor. Photos by the author, except where noted.

Drawing: Christopher Mills.

From Fine Homebuilding #286

To view the article, please click the View PDF button below.

More on home elevators:

Home Elevators – A residential elevator can reduce the price of your new home, and it’ll do the heavy lifting if you can’t.

A Hillside Cabin’s Unlikely Addition – A three-story tower solves steep-site problems by bringing the house to the cars.