Extreme Green

The world’s first Living Building Challenge–certified home is a study in integrated, sustainable design.

Synopsis: The Desert Rain project is the first LBC-certified home, and is also LEED Platinum– and Earth Advantage Platinum–certified. In order to receive these certifications, the design/build team used salvaged, nontoxic, local materials, and created a net-zero-energy and net-zero-water compound. Living Building Challenge certification requires avoiding materials that come at an environmental cost; architect Al Tozer describes his substitutions for plastic and vinyl, and his decisions to leave the roof unfinished to avoid VOCs. The article describes the difficulty in researching and obtaining appropriate materials, and how LBC parameters influenced the structure and layout of Desert Rain.

The Living Building Challenge (LBC)— designed by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI)—is considered to be the world’s most rigorous green-building standard. The LBC is organized into seven performance areas called Petals: Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. Each Petal is then subdivided into Imperatives, which set specific objectives within those categories. The “Desert Rain” compound was the first house to achieve all 20 Imperatives as required by the LBC.

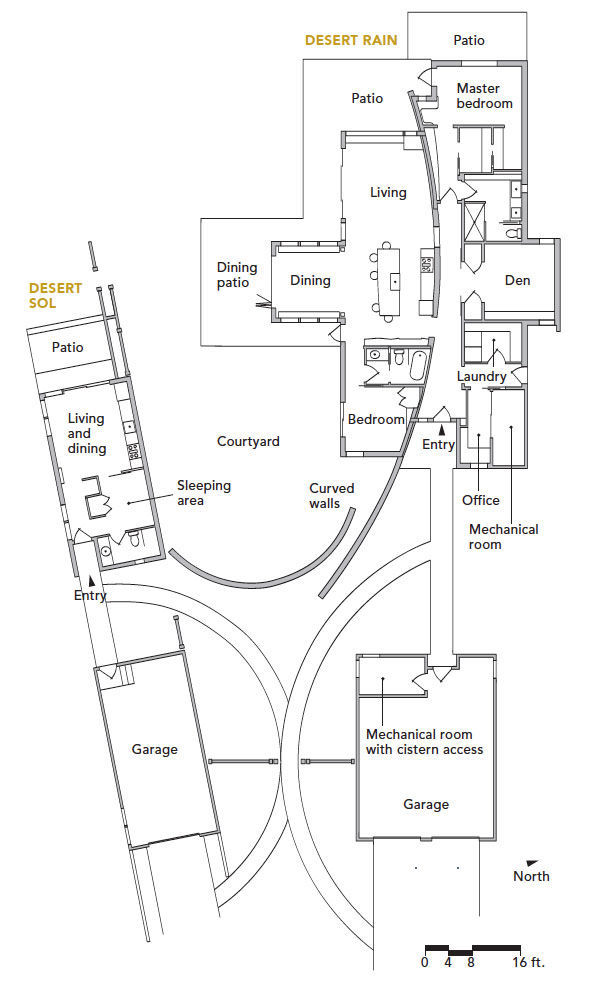

Designed by Al Tozer, ILFI’s Education + Living Building Challenge Director, the world’s first LBC-certified home is located on a 0.7-acre lot at the edge of a historic neighborhood in Bend, Ore. Perched atop a basalt cliff, Desert Rain, a 2236-sq.-ft. one-story home, is the main of three buildings that comprise this residential compound. “Desert Sol” is akin to a guest house and “Desert Lookout” is an apartment-size space. Six years in the making, this project’s course was neither straight nor narrow. In fact, the homeowners only learned about the LBC after the work was well underway. They decided to pursue the certification after hearing Jason McLennan, co-founder of the LBC, discuss the program on the radio.

The team’s first big move was to deconstruct two existing single-family homes, built by mill workers in the 1920s and 1930s. The materials were salvaged for reuse, and the structures were replaced with this net-zero-energy, net-zero-water compound built from nontoxic local materials sensitive to Bend’s natural ecology. Among the 20 Imperatives achieved, Tozer speaks of five that relate to materials: Red List, Embodied Carbon, Responsible Industry, Living Economy Sourcing, and Net-Positive Waste.

ILFI’s Red List names the worst-in-class materials commonly used in the building industry; they are banned from use in Living Buildings. “Even new high-performance building products come at a cost to the environment,” Tozer notes, pointing to all of the plastics, particularly PVC. For the Desert Rain project, he substituted cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) for PVC for the pressurized lines; used ABS for drain, waste, and vent pipes; and spec’d HDPE for the pipes leading from the downspouts to the cistern. He also opted for aluminum-clad wood windows instead of vinyl. Tozer chose Loewen units because of their Forest Steward Council (FSC)–certified wood, and most materials—including the standing-seam metal roof with TPO roofing membrane— were left unfinished to avoid VOCs.

The Embodied Carbon Imperative is straightforward: Minimize carbon by every means available, then offset climate change–related impacts. Teams working on LBC projects are required to use carbon calculators to measure for carbon offsets and carbon credits. The Responsible Industry Imperative ensures third-party verification for sustainably managed and harvested forest products. “It’s about doing the right thing on a global scale,” says Tozer, explaining that the Living Economy Sourcing Imperative supports local economies and communities, which in turn minimizes the environmental impacts of shipping over long distances. And the Net-Positive Waste Imperative mandates recycling, reclaiming, and repurposing construction materials and packaging whenever possible.

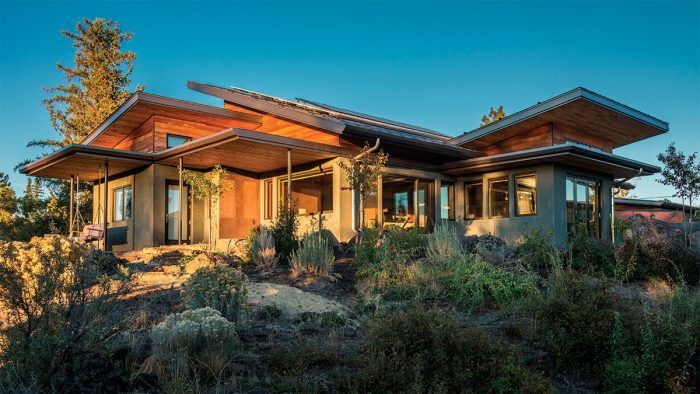

Of course, these parameters, among many others, influenced the look of Desert Rain. The Northwest desert– inspired exterior features a native stone foundation and an indigenous stucco-mixture cladding made by local stucco contractors. Fascias are clad with metal for longevity and unfinished wood soffits are protected by roof overhangs.

Biomimicry principles were part of the design from start to finish; the building operates like a deciduous shade tree. A combination of shed and flat roofs are oriented to provide protection from overhead summer sun and to allow low winter sun to reach deep into the building. The southwest elevation has the best views but is vulnerable to harsh afternoon sun. Tozer raised the west-facing windows and added a flat roof overhang that extends westward, which means the sun is low (and weak) before it penetrates that side of the house.

Inside, American Clay plaster clads all wall surfaces, absorbing and releasing moisture, which helps to modulate indoor-air humidity. The house can be flushed at night to release warm air and trap cool desert air in the slab floor and clay walls, eliminating the need for air conditioning. The radiant-heat floor was mixed using aggregate from the site, and some sections feature madrone wood that was milled locally.

The exposed soffits and some of the ceilings were made with reclaimed pine from the original buildings, and the rafters and collar ties were built from a nearby derelict barn. The kitchen island is a slab of reclaimed walnut from a tree that blew over in a storm, and the Portland-made kitchen sink is recycled aluminum.

The craftsmanship on display throughout the house was born of a commitment made by all involved. “A lot of different tradespeople worked together to make up the expertise needed to design and build Desert Rain,” Tozer explains. “The Living Building Challenge is so unique and so special—you have to avoid using materials that people in these trades use on a daily basis, so there is a learning curve for everyone.”

Their commitment paid off. Though 10 years old, Desert Rain remains far ahead of the pack when it comes to high-performance homes. Of course, much of that gap relates to cost. It’s expensive to build an LBC home. But Tozer sees some progress on that front: “When we did Desert Rain, nothing could be done with an off-the-shelf product without exhaustive research, which required a lot of time, and time is money. The soft costs were much higher than they would be if we were to build it today.” He notes that more manufacturers are providing Declare labels (which show a product’s ingredients and whether they contain Red List chemicals) and certified Living Products. And at the time of the build, there were not as many sustainable and appropriate building materials as there are today.

SPECS

|

– Kiley Jacques is design editor. Photos by Ross Chandler.

More on high-performance and green building:

LEED for Homes Gut Rehab – A century-old Rhode Island house undergoes a LEED Platinum transformation.

What Does Green Really Mean? – Rising energy costs, climate change, and a new social conscience are complicating the way we build.

What Are Passive Houses? – These high-performance building standards and certification guidelines help architects and builders create comfortable, super-energy-efficient houses.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

Graphic Guide to Frame Construction

Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave