Working With Wood Gutters

Builder Scott McBride recounts his time cleaning and rebuilding wood gutters, including the advantages to wood gutters and the key to wood-gutter longevity.

Synopsis: Wood gutters were popular in the early 1900s, before the price of aluminum fell and roll-forming machinery brought our current gutters to market. Builder Scott McBride recounts his time cleaning and rebuilding wood gutters, including the advantages to wood gutters and the key to wood-gutter longevity.

My hometown of Irvington-on-Hudson was developed in the late 19th century as an estate district for wealthy New Yorkers. A railroad constructed in 1849 allowed the Goulds and the Astors to pop off to the country for a weekend and be back in the office on Monday morning. These captains of industry built homes, gatehouses, and carriage barns in an elegant style known as Second Empire that had been developed in France. Typical features of Second Empire architecture include a mansard roof surrounded by an ornate projecting cornice.

By the time I arrived on the scene a century later as an aspiring village carpenter, many of these structures had fallen on hard times. The mansard roof that had once been so fashionable became a white elephant, associated more with haunted houses in movies than with millionaires. Most of the estates had been whittled down by parceling off the land to builders, and the outbuildings were occupied by an assortment of artists and weekend bohemians whose incomes were no match for the voracious maintenance requirements of their aristocratic domiciles. Since I worked for cheap in those days, my eagerness exceeded only by my inexperience, I was often called upon to deal with the result of years of neglect.

Ground zero was the water damage that occurred where drain pipes passed through the cornice carrying rainwater from the shallow built-in gutters above. These gutters couldn’t be seen from the ground, which had a lot to do with the refined appearance of these buildings; but the system depended on a material—tin-plated iron sheets—that was prone to leakage. The constant expansion and contraction of long runs of gutter stressed the joints, and remnants of the acid flux used to solder the joints accelerated corrosion. As a cheap fix most of these gutters had been smeared with roof cement, and when the asphalt cracked water would lodge in the gaps, causing more rust than if nothing had been done at all.

I would set up a scaffold and remove the drainpipe by giving it a good yank. Next I would pry off the bed molding and cut the nails that joined the fascia to the soffit board. Then I would gingerly start tugging at the soffit, looking over my shoulder to consider my best escape route. The decayed drainpipe hole was a frequent entry point for critters, and if you weren’t careful you might be showered with a party mix of acorn husks and desiccated rodent feces when you pulled down the soffit.

The first glance at the now-exposed guts of the cornice was invariably disheartening, looking more like a mushroom farm than the crisply drawn cornice sections I saw in period pattern books. I would poke and pry and sneeze until things began to make sense and then start cobbling the assembly back together as best I could. The process was educational on many levels, but the one overarching takeaway was that built-in gutters, while improving a house’s appearance, have the potential to create one heck of a mess if they aren’t maintained. The same is true of Yankee gutters, which are a close cousin of built-in gutters. (The Yankee gutter stands proud of a roof in a lined trough about a foot back from the eaves.)

It’s not surprising that builders shifted to applied metal gutters that were not only easier to maintain but also caused less damage when they did fail or overflowed. The transition, however, was not as abrupt as you might expect. The missing link between built-in gutters and applied metal gutters was the wood gutter, which flourished for a few brief decades in the early 1900s. As the virgin forests of the Northwest were being gobbled up, it was discovered that clear fir gutters could actually outlive galvanized gutters at a lower cost. This was especially true in urban areas where acid rain was prevalent. Since coal was the dominant fuel for both homes and industry in those days, acid rain was worse than it is now. The biggest fans of wood gutters were railroad companies who employed them on their picturesque station houses. The sulfurous plumes belching from a passing locomotive did little harm to wooden gutters.

Taking a 40-ft.-long old-growth-fir 4×6 and turning most of it into chips in order to make a gutter seems extravagant by today’s standards, but the numbers worked as long as the big trees lasted. The firm of E. M. Long & Sons kept a half-million feet on hand at their warehouse in Cadiz, Ohio, shipping to “many states and parts of Canada.”

The demise of wood gutters came quickly after WWII as wood prices rose and the cost of aluminum fell. The development of roll-forming machinery in the 1960s brought the now ubiquitous ogee-profile gutter to market, largely replacing the half-round metal gutter. The deal was clinched a decade later when portable gutter machines appeared that could crank out any length of gutter on site, conveniently eliminating midspan splices. We take them for granted, of course, but aluminum gutters are a pretty amazing combination of low cost, durability, and overall ease of installation.

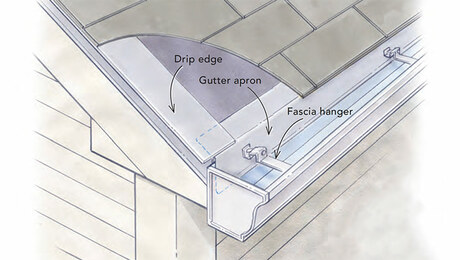

I had occasionally come across wood gutters in my repair work, never expecting to install new ones. Then in 1999 I was asked by a well-known country inn to replace the wood gutters on a cottage they were remodeling. I turned to the only supplier I could find— Blue Ox Millworks in Eureka, California. The company has installation advice on their website and good customer support. The order of redwood gutters arrived on my doorstep in a large crate, and installation was straightforward. One of the nicest things about wood gutters is the ability to miter them together like any other molding— no messy fittings and rivets. Nonstandard angles such as octagon roofs aren’t a problem either. This leads me to wonder if a thick-walled gutter could be manufactured from fly ash, such as Boral’s TruExterior trim, which can be cut and fastened like wood. My experience with fly ash over the past ten years has been good. The material seems impervious to moisture and is dimensionally stable in long lengths—characteristics desirable in a gutter.

Another advantage to wood gutters is the positive threaded connection that can be made between the gutter and a drainpipe. I made a tap for this by grinding gullets on a pipe nipple, but if the hole size is just right, you can screw a thread adapter directly into soft redwood without tapping the hole.

I recently inspected the redwood gutters I installed 20 years ago and they look great. The wood is perfectly sound and all of the miters are still tight. The key, I’ve learned, to wood-gutter longevity is keeping them dry. That means regularly cleaning out debris and avoiding any kind of film finish in the trough that might trap water inside the wood.

You might say my life in the gutter has had ups and downs, but for the most part I’ve managed to keep it on-the-level.

Drawing: George Retseck

From Fine Homebuilding #288

More on gutters:

Fixing Common Gutter Blunders – Design and install gutters as if they prevent damp foundations, peeling paint, and mold—because they do.

Is There Any Alternative to Roof Gutters?

Camouflaging Gutters and Hiding Downspouts – Clever flashing, thoroughly sealed downspouts, and custom channels behind the siding make the rain-management details all but disappear on the California FHB House.