Choosing an Energy-Efficient Water Heater

From an energy standpoint, heat-pump water heaters are the best, but they still struggle for a toehold in the market.

A long-running ad campaign for Maytag featured an affable but underworked repairman who spent his days snoozing in an office chair because the appliances he sold rarely needed any attention. “I’m the loneliest guy in town,” he complained with a sigh.

The story line may ring a bell with John Miles, who heads Eco Systems, Sanden International’s heat-pump water heater operation in the U.S. Although the products he represents are among the most efficient residential water heaters on the market, Miles is still waiting for that breakthrough year when consumers and HVAC specialists finally wake up to the unique advantages that heat-pump water heaters offer.

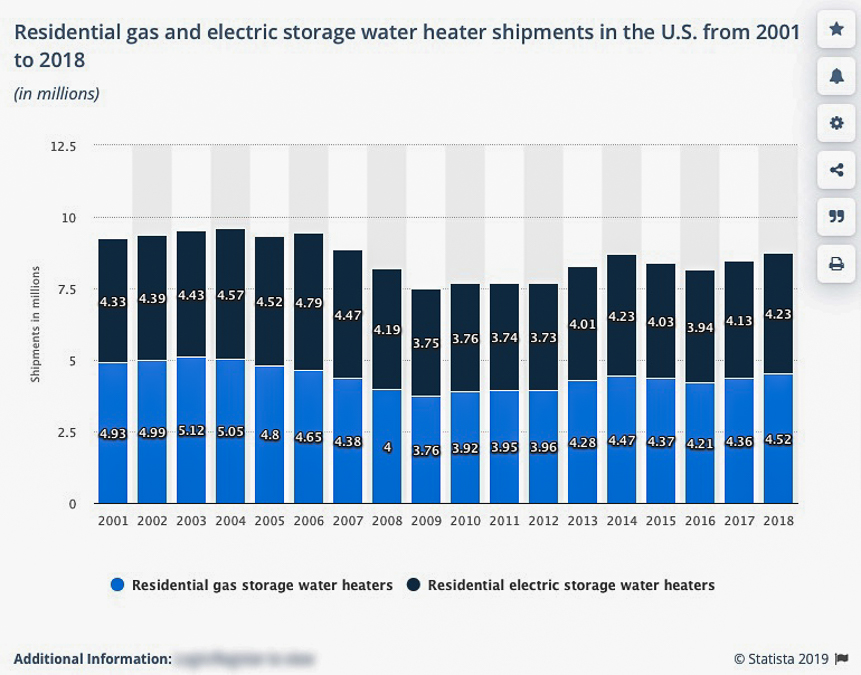

They are head and shoulders above anything else that’s available, but command just a little over 1% of the market—of the more than 8 million residential water heaters sold in the U.S. last year, roughly 100,000 of them were heat-pump appliances, Miles said in a telephone call, and Sanden split-system water heaters accounted for only a small percentage of that.

“It’s been a hard nut to crack,” Miles said.

Heat-pump water heaters are unfamiliar to many U.S. consumers despite widespread success in Japan and Europe. Like other types of air-source heat pumps, including appliances used for space heating, they extract residual heat from the air without burning any fuel directly. Sanden’s product is unique in the U.S.—it’s a split system with the storage tank inside the house and a separate compressor outside. But a growing number of manufacturers offer heat-pump technology in integrated units that combine the compressor and the storage tank.

Heat-pump water heaters are but one option among many for residential water heating. Water heaters with integral storage tanks powered by either gas or electricity are the industry’s old standbys. Manufacturers have increased the energy efficiency of gas models with condensing burners that wring almost all of the potential heat from flue gases. Consumers also can choose an on-demand water heater. Both gas and electric versions are available, and because there is no holding tank for hot water there are no standby losses.

Homeowners may be focused on price and on buying an appliance with enough capacity for their household. But efficiency counts. The Department of Energy estimates that domestic hot water represents between 14% and 18% of total home energy use, more than all other household appliances combined and second only to space heating. At an average of 64 gallons of hot water per day, U.S. households spend between $400 and $600 a year.

Chiseling away at those numbers can add up to big savings over time, but buying decisions are often made quickly and under duress. Miles estimates that 80% of all water heaters are sold on an emergency basis—that is, only when an existing water heater springs a leak or otherwise fails. Homeowners are likely to buy what the plumber has on the truck, not on the basis of what will produce hot water most efficiently. That’s too bad. A little homework would go a long way toward lowering energy costs.

How the government measures efficiency

When someone goes shopping for a new car, one factor to consider is how many miles the vehicle can travel on a gallon of gasoline, the MPG. The Department of Energy has developed a similar metric for comparing water heaters called the Uniform Energy Factor, or UEF. It’s based on standardized tests administered by DOE and ranks performance numerically — the higher the UEF, the greater the energy efficiency. UEFs range from roughly 0.6 to 0.95 for gas and electric models and up to 3.30 for heat-pump water heaters. The idea is that consumers can easily compare the energy costs among similar types of water heaters and choose the one with the best performance and the lowest energy costs.

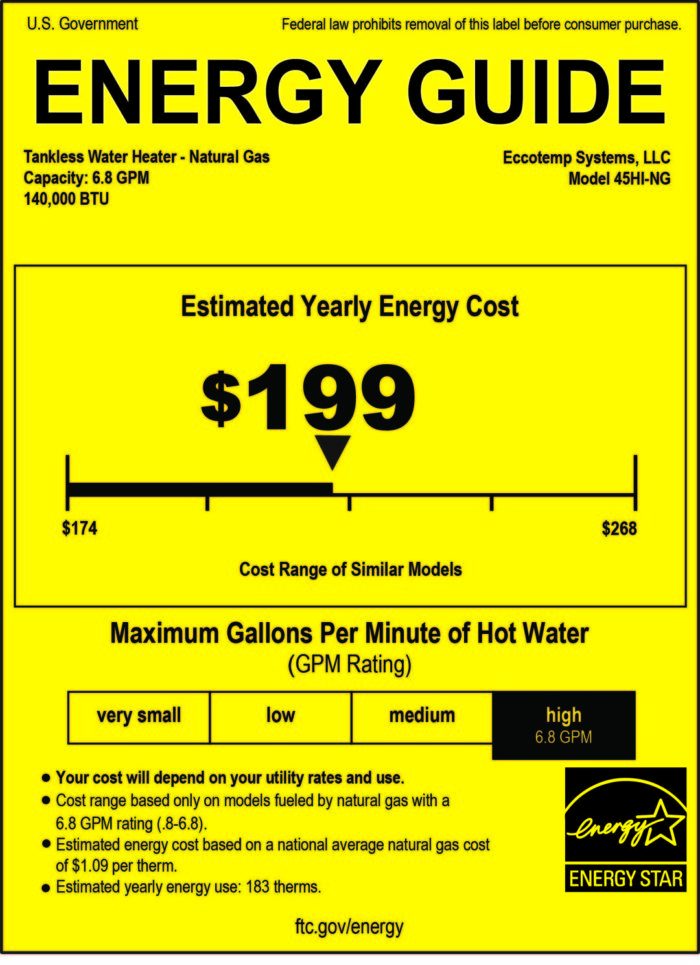

The UEF does not appear on the EnergyGuide labels you may see on water heaters at your local big box store. Instead, the Federal Trade Commission—the agency in charge of the labeling—singles out two other numbers: the estimated annual cost of hot water, and the amount of hot water the appliance will produce in the first hour of use (the first-hour rating, or FHR). If you want to go digging for it, the UEF is available from the manufacturer or see the link below.

In Europe, a single agency administers the minimum mandatory standards for appliances and the information label that goes on them. An appliance gets a letter grade that’s very easy to understand. “A” is great. “C” is OK. In the U.S., there are three separate agencies that work on this issue. According to Chris Granda of the Appliance Standards Awareness Project, the EPA runs the Energy Star program, the DOE sets minimum energy standards and administers UEF testing, and the FTC is responsible for the labels consumers see in the store. “The reason why you don’t see the UEF on the energy label is because no one at the DOE, which is charged with coming up with the UEF and administering it, is talking with the FTC,” Granda said in a telephone call.

There are other important caveats about the UEF. The ratings are based on four levels of hot water use—very small, low, medium, and high—but the DOE warns consumers not to compare the UEF in one usage category with a UEF for a different usage category. If you’re trying to track down the most efficient electric storage water heater in a single volume category, comparing the UEFs (if they are provided) will be useful. Not so much when comparing a “very small” hot water household to a “medium” household, and certainly not when trying to choose between a gas-fired and electric model.

Still, Granda says, the UEF is an important because it’s a common metric that everyone can understand, and it can be reliably replicated. That’s good for manufacturers and utilities trying to promote energy-efficient water heaters. Is it helpful for consumers shopping for a new water heater? “Honestly, probably not,” Granda says. “If you’re just a consumer not connected with a program, it’s just a number. Most consumers care about how much it will cost to run this thing. That’s what the EnergyGuide label is intended to do.”

The DOE maintains an online database of UEF ratings that you can access here. The higher the number, the more efficient the appliance.

Fuel is an important consideration

Local fuel costs and availability are an important consideration. EnergyGuide labels offer an approximation, but they are based on averages rather than actual costs in a particular location. Electricity costs vary widely across the country, and some fossil fuels aren’t available at all in some places. In New England, for example, the network of natural gas lines doesn’t reach very far into rural areas beyond major cities. Liquid propane is probably available, but it’s often expensive.

Further, Granda points out, the cost of electricity has been stable, while the cost of natural gas bounces all over the place, depending on time of year and where you live. The same is true of propane and heating oil.

While fuel availability and pricing is a factor in choosing a water heater, the trend in high-performance houses is away from fossil fuels and toward electricity derived from renewable sources. Appliances that burn fuel—propane, natural gas, or fuel oil—are expressly forbidden in houses certified under the Living Building Challenge, for example.

The question of which fuel to use would seem to favor solar thermal systems. After all, what’s more environmentally friendly, and cheaper, than solar energy? Here, however, the steadily falling cost of photovoltaic panels is eroding interest in solar thermal, which typically comes with higher initial equipment costs. Former GBA Editor Martin Holladay has explored that issue in two posts, and Granda’s own experience bears him out.

“We put solar thermal on our house in Vermont,” he said. “What I would do today is put two PV panels on the roof and run wires to the basement. It would be cheaper to use the electricity to run a heat-pump water heater.”

If electricity is the fuel, go with a heat-pump unit

Heat-pump water heaters are made by a number of manufacturers. There were some hiccups in the market early on—AirGenerate and General Electric both exited the field, and that may have made installers and retailers wary of the technology. But the appliances are now widely available under a variety of brand names, as Martin Holladay explained in this post a year ago.

Although heat-pump water heaters cost more than those powered by electrical resistance heating coils they are far more efficient. At best, a standard electric water heater could have a theoretical energy efficiency close to 100%—nearly all of the energy potential in the electricity converted to hot water. But heat-pump water heaters can return three or more times the energy they consume in the form of hot water and typically show a UEF of more than 3. (When discussing minisplit space heating units, this would be called the Coefficient of Performance.)

Most heat-pump water heaters on the market are hybrids. They combine heat pumps with conventional resistance coils that are activated when the heat pump can’t keep up with demand. The reason is that while very efficient—lots of hot water for a given amount of electricity—they also are relatively slow when in heat-pump mode.

Another consideration is where a heat-pump water heater can be installed. The heat pump will lower the temperature of the air in the space where it is installed, which may be a consideration in some climate zones in fall and winter. There also are minimum space requirements. A.O. Smith, for example, recommends a heat-pump water heater be installed in a space no less than 750 cubic feet. Although there is an energy penalty, installations are possible in smaller confined spaces with a ducting kit that controls where air is drawn from and where exhaust air goes once it’s been through the compressor.

Sanden’s SanCO2 is different from the rest of the field in two respects. First, the compressor goes outside and the storage is located inside; they are connected only by water lines. That keeps the compressor noise out of the house and eliminates any concerns about low outlet air temperatures. Second, the unit uses C02 rather than a conventional refrigerant. With a global warming potential of 1, C02 carries much lower environmental risks than the fluorocarbons that are typically used in heat pumps. According to Miles, the technology also produces higher water temperatures than other heat-pump water heaters, and does so without any backup resistance coils.

The split C02 system is very popular in Japan, in part because of the country’s love of soaking tubs that require a lot of very hot water, Miles said. The water heaters can easily produce 150-degree water, which when mixed with cooler water to a standard 120 degrees for distribution, goes a long way. In Japan, some 500,000 units are sold each year, five times the total U.S. market for heat-pump water heaters.

Sanden’s biggest problem has been cost. A residential system, Miles said, runs about $3,500, double the price of other heat-pump water heaters on the market. High efficiency and other benefits should help the company grow in the U.S., he added, but these appliances now face the same uphill fight that ductless minisplits once did.

“Certain industries have a huge amount of inertia,” he said. “And sadly, the HVAC industry is one of those industries. It’s taken 20-plus years for minisplits to get to a position where it’s no longer something like seeing a white rhino. Everyone has been conditioned to look at the first cost of stuff and not calculate out the life cycle cost. If you looked at that and said, ‘My hot water cost me $500 or $600 a year for the next 10 years, that’s $6,000. If I invest a couple of thousand more, all of a sudden that number becomes negligible.”

If you want an Energy Star-approved model, you can find a list here.

Condensing gas models are best, for now

Although not the most efficient on the market, a tank-style water heater that burns natural gas is an economical way of providing domestic hot water in many markets. There are two basic choices in this category, standard and condensing. A conventional water heater vents exhaust gases into a masonry or metal flue. A condensing unit includes an extra heat exchanger that pulls residual heat from the flue gases before they go out. Efficiency goes up, and the temperature of the exhaust goes down. The stack temperatures are low enough to allow the use of plastic pipe for the exhaust rather than a conventional chimney.

Keith Kuliga, assistant product manager at Bradford White Corp., says condensing gas water heaters are typically 5% to 10% more thermally efficient than non-condensing models.

Tankless (on-demand) water heaters also are available in both condensing and non-condensing models. Condensing models are more expensive but also more efficient. Rinnai lists the UEF for non-condensing models from 0.79 to 0.82; for condensing models the range is from 0.85 to a high of 0.93. David Federico, brand manager for Rinnai America Corporation, says tankless gas models are roughly 20% more efficient than gas tank water heaters. The DOE’s directory of water heaters shows tankless gas appliances typically have UEFs in a range of 0.80 to 0.90 and up while tank-style water heaters show UEFs beginning in the 0.60 range.

Electric tankless heaters are another option, and they report very high UEFs, up to 0.98. But this thermal efficiency comes with some inconveniences—mainly a huge power draw. Rheem’s RTEX-24, for example, draws 100 amps at 240 volts and requires three 40-amp breakers. Given that some older houses still have 100-amp panels in the basement that run all appliances and plugs in the house, and the standard for a new home is 200 amps, that’s a lot of electricity. Critics also point to the intermittent but significant spikes in electrical demand as a problem for the grid.

What’s in the future?

At the moment, an electric heat-pump water heater holds a sizeable lead in the efficiency department, although that comes with a higher first cost. There are at least two, and probably more, emerging technologies that should help lower the amount of energy required to produce hot water even further.

One is a heat-pump water heater whose compressor is driven by gas, not electricity. The technology is at what the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance calls the “nascent stage,” under development for the residential market but not yet available commercially. The technology should significantly improve current efficiencies for gas water heaters.

Aaron Winer, senior program manager for NEEA, said one manufacturer expects to have such a water heater on the market by 2022. Larger, commercial units are already available. The UEF of these appliances can hit the range of 1.2 to 1.4, a big step up from the most efficient gas-burning water heaters currently available but still far below the efficiencies of electric heat-pump water heaters.

“A big difference between these units is that the currently available technology costs in the range of $4,000 for the unit and installation,” Winer said by email, “where a gas heat pump-water heater is projected to cost $3,000 or less–all while delivering a significantly higher level of energy savings.”

The other area for improved efficiency is not in the equipment itself, but how it is used. “We see improved technologies and/or solutions based on a systems approach,” says Geoff Wickes, another senior program manager at NEEA. “Plumbing equipment, appliances that use less water, shorter, more appropriate plumbing runs, drain water heat recovery, proper use of on-demand circulator pumps, and better insulation on pipes.”

Manufacturers also are adopting wi-fi technology. For households, the equipment allows greater control over when and how hot water is produced. For utilities, it means the potential for better managing loads on the grid and avoiding construction of new peaker plants. Rinnai, for example, now offers wi-fi features on a couple of its tankless heaters and says they can be paired with smart home technology, such as Amazon’s Alexa devices, to allow homeowners precise control of a hot water circulation system. A third-party device called the Aquanta is an add-on that allows water heaters to be controlled remotely.

Another demand on manufacturers is the increasing pressure to eliminate anything that burns any fuel—wood, oil, gas—and replace it with an appliance powered by electricity. Ideally, electricity derived from renewable sources. Even companies completely invested in gas technology, such as Rennai, are keenly aware of the trend.

Asked about what a non-combustible future will mean for his company, Federico said he couldn’t be specific, but added, “We look to expand our product portfolio. There are a lot of conversations about it. We’re very aware of it.”

In the meantime, the question for Miles and other heat-pump water heater manufacturers is how to get their market share out of the basement.

“That’s an interesting question,” Miles said. “I think that all of the manufacturers are asking the same question of themselves. There are many parts to this, especially as at least 75% of the water heaters sold are for customers who need a unit on an emergency basis.”

Better consumer understanding of potential savings would help, as would government and utility rebates, and more decisive government directives on efficiency. And then there are the plumbers.

“The majority of plumbers hate new technology, especially when they can install a gas or electric water heater and not see it again for 5 to 10 years and then just replace it at that time,” Miles said by email. “The outcome from this is they don’t want to install a new product they may have to service unless the homeowner really wants it and they are going to lose a sale.

“It has taken tankless products over 20 years to become about 20% of the 4.2 million gas water heaters sold annually,” Miles concludes.

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. Scott Gibson is a contributing writer at Green Building Advisor and Fine Homebuilding magazine.