Staircase Renovation

Loose, tilted flights signal trouble underfoot, but even major problems can be fixed with screws, blocks and braces.

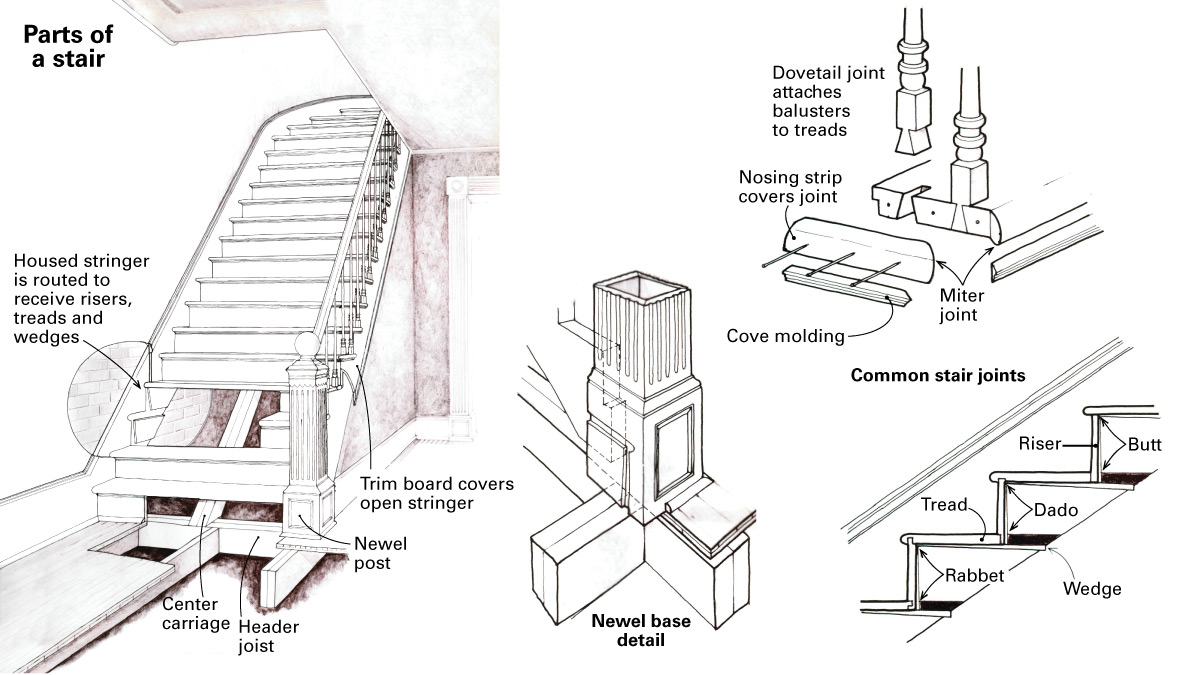

Synopsis: Originally featured in Fine Homebuilding issue #1, this article by Joseph Kitchel describes basic stair construction, how to diagnose stair issues, and how to make common repairs to either the superstructure or the substructure. The included illustrations show common stair parts and joints, how to create a platform for major repairs, and smaller details such as newel-post attachment.

There seems to be a great deal of reluctance among renovators to tackle any kind of stair rebuilding. I have seen many beautifully renovated homes with sagging staircases, loose balusters and makeshift railing supports. People who wouldn’t think of leaving cracked plaster cracked or sagging floors unshored will put up with staircases so crooked they would make a sailor seasick, and squeaks so loud they wake the whole family at night.

Procrastination and lack of understanding of the mechanics of stair construction are at fault here. No one seems to know quite where or how to start, or who to call to do the job. To be sure, attacking an ailing stair takes courage, resolution and perseverance. It is one of the dirtiest and most disruptive renovating jobs.

The stairway is the spine of the multistoried row house. It links the sometimes minimal area of individual floors into what can be a spacious and accommodating floor plan. Because changing the stairway can seriously affect the physical flow of people and spoil the aesthetics of the whole interior design, it is far better to renovate than redesign or reposition.

Parts of a stair—Each step consists of a riser, the vertical portion that determines the height of each step, and the tread, the part on which you step. The dimensions of steps must be consistent within flights, though they may vary from one flight to the next. Variation within the flight will break the stair-user’s physical rhythm and cause tripping. Tread widths may vary in the bottom two or three steps of the main flight for aesthetic purposes, and at the top of a flight, where pie-shaped steps are needed to negotiate a curve. Riser height, however, must not vary.

The newel post, usually decorated with paneling or carving, supports the railing at the bottom of the flight. Though it gives the impression of being heavy and sturdy, after years of being swung around by ebullient children, it has probably loosened enough to sway from side to side or lean out toward the hall. The vertical supports of the railing, aligned more or less behind the newel post and marching upward with each successive step, are balusters or spindles, which are dovetailed into the treads.

Keeping the balusters from slipping out of their joints on the open side of the staircase are the noses, continuations of the molding that forms the front edge of the treads. These noses are removable and not part of the tread itself.

On each side of the stairs are the stringers, which hold the risers and treads. The stringer attached to the wall is usually routed or plowed out to receive the steps; this is called a housed stringer, and it produces a strong, dust-tight stairway. The outside stringer may be open or closed. Stringers may be simple, laminated with other pieces to form the curves of the stairs, or partially concealed by decorative filigree…

From Fine Homebuilding #297

To read the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.