Problem-Solving Through Stair Landings

International Residential Code requirements for intermediate and odd-shaped stair landings.

Synopsis: Intermediate stair landings can help solve house-design quandaries. Adding a landing can allow for greater heights between floors, for example, or can be used to eliminate a required handrail. Code-minimum landings also don’t always have to be square. Code expert Glenn Mathewson explores the code provisions for stairway landings and explains the requirements of the code, and how these requirements allow for greater flexibility when it comes to stair and whole-house design.

Stairways and their guards have been an artistic focal point of house design since long before the invention of building codes. When model codes began to address stair design for houses in the mid-1900s, the provisions were carefully crafted to maintain the long-appreciated architectural freedom. Uniformity of treads and the dimensions of winder treads—pie-slice-shaped stairs that wrap around a bend in a flight of stairs—were the first stair components addressed, followed by maximum rise and minimum run. This pattern of incremental code development has continued, with more provisions for stairways in each new edition. While “more provisions” is usually thought of as “more rules,” new rules are often meant to provide more allowances, not more prohibitions.

Stairway landings are a good example. From the first edition of the International Residential Code, requirements for landings were straightforward but somewhat limiting. A landing or floor was required at the top of each stairway. These landings had to be at least as wide as the stairs and at least 36 in. “in the direction of travel.” The slope of the landing was also limited to 1⁄4-in-12, the same as stair treads.

These provisions are about all that’s necessary for most stairway landings. And more often than not, these features aren’t even noticed. On decks, the top landing is usually just an indistinguishable part of the deck. The bottom landing is often something existing or integrated into the landscaping, like a sidewalk, patio, or flagstone area. There are landings that take center stage, however, and they have an opportunity to stand out with creative design. A landing between two flights on a stairway—especially one that turns—can be a distinguishing feature on its own.

An intermediate landing on a stairway can serve a few functions. It can look architecturally pleasing, as it may allow a long stairway to turn and fit better to the shape of the space it’s in or around. It’s also safer for those with mobility challenges, as it breaks up a long ascent into two multiple shorter stairs and provides a safe place to rest. If heading the other direction, it may shorten the distance of your tumble in an accidental fall. And landings can help solve other house-design quandaries; the IRC doesn’t limit the total height of a stairway between floors provided that there are intermediate landings at least every 151 in. (R311.7.3). Adding a landing can allow for greater heights between floors.

Intermediate landings can also be used to eliminate a required handrail. A handrail is often a design-afterthought nightmare, as the guards that protect people from falling off the sides of stairs may not have been designed to accommodate a handrail in an attractive way, or an adjacent wall surface may be irregular or architectural and not conducive to one. In deck construction, some finish materials used to create a certain look may not come in dimensions or grades needed to create compliant handrails. Since handrails are not required for stairs three rises or less, you can add an intermediate landing or two to avoid the need for what would be an awkward handrail. Rather than a nine-rise flight of stairs with a handrail, you could choose three runs of three-rise stairs with intermediate landings instead.

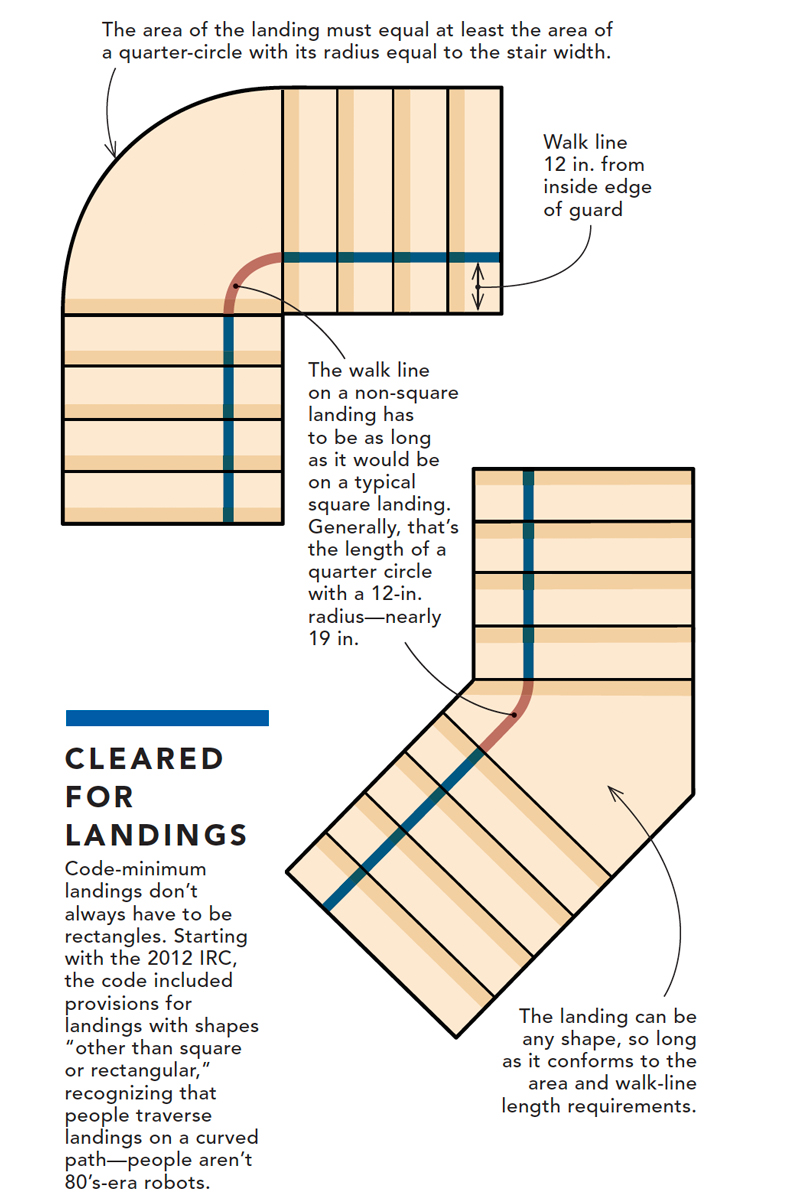

And these landings don’t always have to be rectangular. The common belief that stair landings have to be square or rectangular is an understanding gleaned from early versions of the code, which stated: “Every landing shall have a minimum dimension of 36 inches measured in the direction of travel.” But when the following sentence was added to Section R311.7.6 in the 2012 IRC, it was made clear that creative designs are welcome in some instances: “Landings of shapes other than square or rectangular shall be permitted provided the depth at the walk line and the total area is not less than that of a quarter circle with a radius equal to the required landing width.”

In a rather cryptic manner, the code is allowing a landing at a turn in a stairway, between two flights, to be non-square. The core concept is that people don’t walk in right angles as they turn on these landings; they walk in a curve, usually closer to the inside. If you’re turning to the right on an intermediate landing and heading to the next flight of stairs, why do you need the outer corner of the landing at your left? You don’t. Cut it out if you’d like. The code simply wants you to have two things in these conditions: A long enough step to break your walking rhythm, and a place to rest.

The earliest codes for stairs included provisions for uniformity in the geometry of treads and a recognition of winder treads and how to measure the uniformity of their “run” (tread depth). Both of these concepts inform this discussion of intermediate landings. A winder must have a tread depth that’s consistent with the winder treads before and after it so people walking up and down it can maintain their stride without tripping. In contrast, a landing is meant to break the uniformity of someone’s step and put an obvious end to their walking rhythm. For this reason, the uniformity of rise and run can be different in the stairs on each side of a landing.

Winder tread depth is measured along what the code refers to as the “walk line.” The walk line is the point on a tread 12 in. from the narrower side of the winder treads (the inside of the turn and measured from inside of the guards), which is where the average user walks along a curved stair. To anticipate where on a non-square landing a stair user would most likely walk at a turn in the stairway, the code uses the walk-line concept from winder treads: The distance along the arc of the walk line of a non-square landing (12 in. from the turning side) must be at least as long as the same distance on a square landing. Generally speaking, it’s the length of a 90° arc with a 12-in. radius (just under 19 in.), but the location of the guards will affect this generalization. To allow people sufficient space on the landing to rest, the total area of an odd-shaped landing must be no less than the area of a quarter circle with a radius equal to the width of the stairs. The outside edge doesn’t need to be circular, but that is the most compact shape.

There’s little difference between designing an odd-shaped landing with these mental gymnastics and designing a single winder tread between two standard stairs (which is also permitted). A landing, however, will allow you to have taller individual stairs on each side. A landing would also create two separate “stair flights,” while a winder tread is just another step in a single flight.

Continuous handrails are only required for each stair flight, so they can end and begin at an intermediate landing. That said, the continuous rail can also be interrupted at a turn in a stairway at a winder, so there is no benefit in that regard to either design. What is different is when landings are included, there is no limit to the vertical rise of the stairway. With winders, there is.

Understanding these newer code provisions allows designers and contractors more freedom than they had previously when there were fewer “rules” in the code. Though it’s seemingly a paradox, more code can mean more freedom— but it’s not an inspector or plan reviewer’s job to teach this freedom to you. If you want to know the freedom the code allows, you’ve got to know the code. Make it your friend. It’s not as bad as the rumors you hear—not all of them, at least.

–Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with buildingcodecollege.com.

Drawings: Melinda Sonido

From Fine Homebuilding #298

Related Link: