Successful Vapor Control

Vapor drive isn't as obvious as air or water leaks, but the potential for mold and rot is just as real.

Synopsis: Though the immediate problems associated with poor vapor control are less noticeable than bulk water, they can have destructive impacts. As building materials advance and energy codes continue to tighten up building envelopes, it becomes more and more important to focus on the effects of moisture intrusion from vapor drive. Durable wall assemblies must consider inside and outside sources of water vapor, and allow drying to exceed wetting over the long haul. This article depicts a number of acceptable wall assemblies and their appropriate use of vapor retarders by climate zone, and also includes a series of questions to determine the best vapor retarder and exterior insulation combination based on your wall assembly and climate.

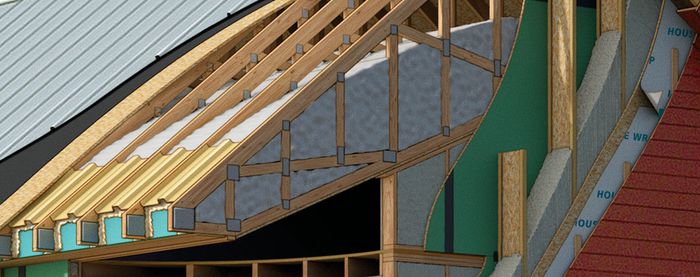

Building materials and wall assemblies have evolved significantly over the last century. Where walls were once sheathed with lumber boards, most homes now are sheathed with plywood and OSB. We replaced interior lath-and-plaster with gypsum wallboard. Insulation became the norm, and energy codes have continued to add even more and different types of insulation. These changes affect the moisture behavior of walls and, when not thought out or tested, can cause problems. For example, starting in the 1990s, we discovered that improved flashing and water-resistive barrier (WRB) requirements were needed to better protect water-sensitive materials in walls such as plywood, OSB, and drywall.

We also realized that as insulation levels increase and heat flow through wall assemblies decreases, air leakage becomes more of a problem. Air leaks allow airborne moisture (vapor) inside walls, where it can condense on cool surfaces and lead to mold and rot. It also wastes a lot of energy. The solution in the energy code was to tighten up building envelopes to limit air leakage. Unfortunately, we have paid less attention to improving vapor control in step with the changes to wall assemblies over the course of several decades.

Water vapor is simply water in its gaseous state. We experience its effects on our own comfort: When humidity spikes on a hot day, it feels much warmer than the temperature alone would indicate. Many building components— especially wood— are affected by water vapor as well. If you have a door that sticks in the summer but not in the winter, it’s likely that water vapor is the culprit. But this is a minor nuisance compared to the damage water vapor can wreak inside a wall.

The problems associated with poor vapor control are not as immediately obvious as those from bulk water or air leaks, and their solution even less so. Vapor diffusion through materials, or vapor drive, is a much more subtle form of moisture intrusion. While rain leaking through an improperly installed window may be obvious straightaway, water vapor is diffuse and invisible, and capable of causing damage slowly and often imperceptibly. And while the damage from a poorly flashed window tends to be localized to the portion of the wall where the leak occurs, insufficient vapor control can have destructive impacts that, over time, affect a much larger area than a water or air leak.

The extent of this problem and the need for improved code provisions was realized in a review published in 2015 by the Applied Building Technology Group, which can be found online at appliedbuildingtech.com/rr/141003. It assessed data from both good-and-poor-performing walls in various climates and provided a rational basis to begin to fill gaps in the code.

New code rules help

The International Code Council responded to poor water-vapor control with improved provisions in the 2021 International Residential Code (IRC). Even if your jurisdiction is using an older version of the IRC, you may want to implement the 2021 version’s vapor-management prescriptions right away, because older versions may allow for some risky wall assemblies.

In heating climates, the effects of excessive vapor diffusion into wall cavities typically manifests as repeatedly wetted sheathing (cycling above 20% moisture content each winter), with or without condensation or rot. In cooling climates or anywhere air conditioning is used in the summer, vapor problems can show up as mold or condensation on the back side of drywall.

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of possible wall configurations and material combinations that affect water-vapor behavior. The 2021 IRC does a good job tackling the complexities of the vapor-control issue. Code writers had to balance the variations in water vapor’s behavior across the nine U.S. climate zones with the various properties of the wall’s interior layers, exterior layers, and insulation, as well as the insulation strategy (e.g., cavity insulation only or cavity plus continuous exterior insulation).

Blocking water vapor is imperfect

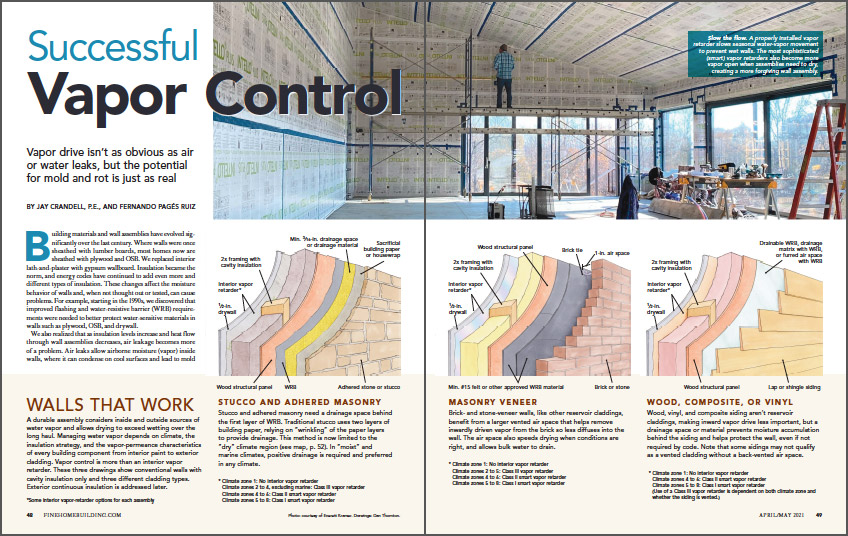

In most climates, the traditional method of reducing moisture accumulation inside a wall is to use a suitable interior vapor retarder. The 2021 IRC follows this conventional approach for wall assemblies without exterior continuous insulation. What’s still missing from this approach, however, is specifications for minimum permeance requirements for materials on the assembly’s exterior side when a Class I or II interior vapor retarder is used in colder climates as specified in the code.

Unfortunately, most exterior materials (except WRBs) do not have any product-specific perm-rating information or requirements, or the information we have about them is too generic to be very useful (for more on perm ratings, see facing page, left). For example, research data indicates that OSB’s permeance may vary from less than 2 perms to as much as 5 perms. Depending on the climate and the vapor retarder used inside, this difference in exterior sheathing permeance can have a significant impact on its moisture content during the winter. Fortunately, this is rather easy to remedy by going beyond code minimum and using a Class I variable-permeance (smart) vapor retarder in colder climates.

When Class III interior vapor retarder is used without exterior insulation, it becomes important in climate zones 4 and higher to use vented claddings, such as vinyl siding, to aid drying and prevent excessive wetting of the sheathing during winter. The sheathing permeance is important too.

From Fine Homebuilding #298

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Related Links:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Nitrile Work Gloves

Utility Knife

Disposable Suit