Building in the Southwest

Asphalt shingles are rare, wood and paint don't hold up to the UV exposure, and shading and drainage are critical.

I’m a builder in Massachusetts who’s planning to retire soon. My wife and I will move from the Northeast to the Albuquerque, N.M., area and build our last house. Clearly, the climates are very different. Big picture, how does that affect the materials and how we should think about the design of our house?

—Joe via email

David Crosby, a builder and construction consultant in Santa Fe, N.M., replies: One of the foremost considerations for durability, ease of maintenance, and lower operating costs in the Southwest is climate. With an average of about 300 days of brilliant sunshine a year, it is very unusual to see cloudiness that lasts more than two or three days. And the greater intensity of the sun has implications for the way we build. There is useful info and maps from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) available at nrel.gov/gis/solar.html.

An approach that works elsewhere in the country can result in a badly overheated house in the Southwest. For much of the country, a daily variation in temperature may be 5°F to 10°F depending upon the time of year and humidity. In the Southwest, a 35°F to 40°F variation is not uncommon, and it’s entirely normal at higher elevations for plants to be growing on the south side of the house with snow on frozen ground on the north side. Calculating solar exposures and window placement and using overhangs to shade the house between the spring and fall equinoxes is inexpensive and effective. Whether a house is intended to be passive solar or not, this must be taken into account not just for thermal gain but also for materials selection and envelope design.

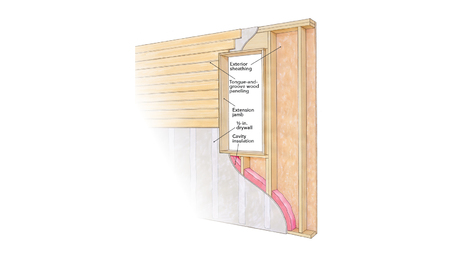

Stucco is common in the Southwest because it withstands the solar radiation and temperature extremes better than conventional siding and paint. Flashing and drainageplane details are every bit as important in the desert, especially with synthetic stucco. When it rains here, it rains hard.

Architecture in the Southwest, especially in New Mexico since the turn of the 20th century, often incorporates low-slope roofs and parapets reminiscent of older adobe construction. For durability, ease of maintenance, envelope integrity, life-cycle cost, and working out solar exposures using overhangs and porches, you’re going to be better off with a traditional pitched roof with metal or clay-tile roofing. Hip roofs with dormers on adobe homes are common throughout northern New Mexico in rural areas, but you won’t see asphalt shingles very often—the intense UV and frequent freeze-thaw cycles are very hard on them. If you are stuck with a low-slope roof, it’s best to observe best practices (see “Guide to Low-Slope Roofing,” FHB #269), paying particular attention to the number, size, and location of roof drains. UV and hail resistance is also a consideration; premium-quality modified-bitumen roofs with a reflective coating tend to hold up well.

One of the most common and serious problems in modern Southwest homes is drainage. It doesn’t rain very often, but when it does you can get a lot of water in a short period of time, and it can do a lot of damage. Unlike the relatively stable soils of New England, it is common to find collapsible soils, expansive clay, poorly graded fine alluvial soils, well-graded gravel, or cobble; sometimes two or more of those types on one site. You’ll want to make sure that the provisions of International Residential Code section R401.3, concerning positive grading away from the house, are observed.

Photo: Amadeus Leitner, courtesy of NEEDBASED, Inc.

From Fine Homebuilding #299

RELATED LINKS: