Tracking Down the Cause of a Flooring Installation Gone Wrong

Why does the solid wood floor downstairs squeak everywhere while the flooring upstairs does not?

Mopsy has been doing some work for a Vancouver, British Columbia, family with a pesky wood-flooring problem that he’d like to help them solve.

As Mopsy explains in this post in FHB’s Discussion Forum, the 3000-sq.-ft. house has two levels built over a 3-ft. crawlspace. As part of a whole-house renovation, Mopsy’s clients installed a new hardwood floor in the upper part of the house. The prefinished, 7-in.-wide hickory sat for two weeks before it was glued and nailed down.

“The end result was an installation that to this day has not peeped a sound,” Mopsy says.

But when it came time to install new flooring on the first floor, the results were not nearly as good. Once again, the installers used both glue (Titebond) and nails, dividing the floor into two phases a week or two apart.

“The whole main floor creaks,” Mopsy writes. “The area of least creaking is the first half that was installed. It does creak but not nearly as bad as the second half installed couple of weeks later. One cannot walk anywhere without the creaking. It sounds like large toothpicks snapping with every step!”

The flooring was installed just five days after it was delivered to the house, with all 2000 ft. stacked in the living room. The supplier has tried to blame low humidity (in the 40% range) and suggests waiting until summer to see what happens.

“Some spaces have begun to appear between boards around the home,” Mopsy writes. “A quarter can be stood on end in some places. In the kitchen, crumbs have more recently started to get between the boards.”

That original post dates from 2012, but recently an FHB reader took another swing at explaining the cause. Let’s have a look at this nearly decade-old saga.

First, what about the glue?

In the trouble-free part of the house, the installer used an adhesive called Fortane LD, a moisture-cured urethane adhesive that was applied with a square-notched trowel. When flooring was installed on the first floor, the glue was Titebond, which was applied in a zig-zag pattern with a pneumatic glue gun.

Is the choice of an adhesive part of the problem?

“I would never use tube glue to hold hardwood and if I did, it would be a product like [Loctite] PL Premium—a urethane glue,” Calvin says. “But full spread is a different subject than zigzag. There’s more contact with trowel down.”

In addition to questioning the adhesive, Calvin also wonders whether the location of ducts beneath the floor might be a contributing factor. “Is the crawl dry?” he asks. “Is there a moisture barrier put down?”

Although there are several varieties of Titebond glue, including one that’s troweled on, DanH points out that they are generally a hard glue and stiffer than typical construction adhesive. “Unless the particular stuff was different from this it would seem to be a poor choice for flooring where there must be some give.”

Cussnu2 thinks that if the glue came out of a tube in a fairly thick ribbon, the flooring would have to be worked around quite a bit in order to flatten out the bead and allow full contact between the flooring and the subfloor.

“My guess would be that the glue is serving as a spacer between the floor and the subfloor, allowing it to flex when it is walked on,” Cussnu2 says.

Did the installer check moisture level?

Calvin also asks whether the installer used a moisture meter to check the floor and the subfloor.

The moisture readings between the flooring and the subfloor must be relatively close, Calvin says. Wide differences can affect the flooring.

“Though most don’t, good flooring installers will check the content of the subfloor and the finished floor before work beings,” he adds. “That’s what an acclimation period is all about. Bring the new stuff in concert with the existing since you’re putting it right on top of it.”

Mopsy is certain the installer never checked the moisture content of either material. The hardwood remained stacked and bundled for less than a week before the installation began.

Moisture readings should be taken on the subfloor, on the hardwood, and in a few spots on existing woodwork throughout the house, says Silvernails. Results should not vary by more than 2%. The hardwood should have been removed from packaging and stickered with a fan lightly circulating air around it.

“The slight cracks between boards is a definite sign that the wood was not fully climatized,” Silvernails says. “Sometimes this can take up to a month.”

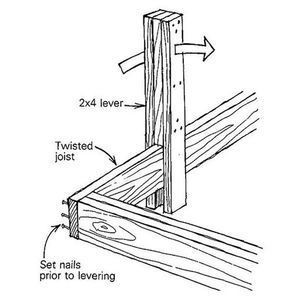

The squeaks, he adds, are coming from boards that are moving up and down on a nail. “We run into a lot of problems such as this up here in Whistler, B.C.,” he says. “Wet winters and dry summers.”

Choose your subs wisely, adds IdahoDon. “It sounds like you have guys who don’t know what they are doing and your client is the loser,” he says. “Shame on the homeowners for not hiring the guy who did a good job the first time around. How many jobs of the new flooring guys did the homeowners visit that were similar to theirs? None. Was this most likely based on a low bidder getting the job? Yes. Stupid is as stupid does.”

A new theory emerges

That original thread left us with a couple of possible causes—the wrong adhesive, an adhesive that was applied incorrectly, or possibly a mismatch in moisture content between the flooring and the subfloor.

Just recently, an unnamed user (we’ll call him User-754) made another suggestion that could explain the widespread squeaking problem: the flooring itself. Apparently assuming that the floor is an engineered product with a layer of hardwood veneer on top and a core of plywood, User-754 suggests the two might be parting ways. He’s run into that problem himself.

“After a lot of back and forth, with the installers insisting it wasn’t their install that was the problem, but the floor itself, they came back to try to fix the problem with some spot-drilling and glue injection,” User-754 says.

They drilled through to the subfloor and injected glue, and also drilled just below the laminate surface and did the same thing. “Drilling and gluing to the subfloor did nothing but the partial did the trick. Turns out the top layer was delaminating after all. We ended up drilling into close to 20 boards and so far so good.”

Our expert’s opinion

Builder and remodeler Mike Guertin has these thoughts:

It’s always too late after wood flooring is installed to make repairs—especially with nail-down and glue-down systems. Any attempts short of removing the problem flooring and starting from scratch are rarely effective. And it’s difficult to pinpoint the root cause of a problem, whether it’s cupping, crowning, buckling, gapping, or squeaking and popping. There often are several contributing factors that alone may result in an annoyance but together lead to a complete failure—and others quoted here have done a good job of noting many of those factors. Without a thorough on-site evaluation we will never know what actually caused the gapping and popping problems in this house.

A highly skilled wood-flooring installer not only knows how to install flooring effectively, but also understands all of the variables that have to be considered—and addressed—before the first board is placed. We can’t install wood flooring the way it was done 20 or 40 or 60 years ago. The wood flooring products we install today are different, the subfloor is different, and the houses are different. I recommend that installers, both new and experienced, read the revised version of the National Wood Flooring Association’s (NWFA) “Wood Flooring Installation Guidelines.” It’ll set you back $110, but will save much more than that by helping you avoid problems with an installation.

Here’s a list of the factors that I evaluate when selecting and installing a wood floor:

- The flooring product. Is it compatible with the house, the seasonal temperature and moisture conditions in the house, and customer expectations? Wide-plank, live-sawn, or plain-sawn flooring isn’t a good choice in a leaky old house with cold winters and humid summers without air conditioning.

- What is the floor system over: conditioned living space (second floor of a two-story home), or an unconditioned basement or crawlspace?

- What is the subfloor, what condition is it in, and how is it fastened to the joists?

- What is the joist spacing?

- What is the direction of the flooring in relation to the joist direction?

- What is the HVAC for the house and how is it operated over the course of a year?

- What is the local climate?

- What are the clients’ expectations?

- What’s the likelihood that clients will follow occupancy requirements regarding space conditioning?

Check and compare site conditions to the manufacturer’s installation requirements and the NWFA manual. Don’t install the flooring unless all conditions are met. And document, document, document all conditions before and during installation. They include:

- Moisture content of the subfloor

- Moisture content of the wood upon delivery

- Moisture content of the wood upon installation

- Relative humidity of the house

- Temperature of the house

- Operation of the HVAC system several weeks before, during, and after installation

The flooring should be acclimated before it’s installed, which means placing it in the room with bundles opened and the flooring stickered to enhance airflow for the recommended period of time. Make sure to follow manufacturers’ recommendations on fasteners (including type, length, and spacing). Use the correct underlayment, and follow instructions on adhesive type and how it is applied. Allow the required spacing around the perimeter of the room to walls, thresholds, and other obstacles. Finally, plan for expansion and contraction joints.

Scott Gibson is a contributing writer at Fine Homebuilding and Green Building Advisor. Mike Guertin, an FHB editorial advisor, is a builder and remodeler in Rhode Island. Reader comments may have been edited for clarity.

RELATED LINKS