What Is “Good Enough” Trim Carpentry?

A veteran carpenter considers how to measure the quality of finish-carpentry work without a building inspector to pass judgement.

Synopsis: Veteran trim carpenter and editor-at-large Kevin Ireton discusses the difficulty of deciding what constitutes good trim carpentry work. While there are some industry standards to point to, within these parameters the quality of work depends on so many factors—time, budget, difficulty, location, and even time of day. For the professional, “good enough” might mean the worst possible result—but one that many others would never question.

My friend Buffalo is trying to finish a custom kitchen renovation. Unfortunately, the homeowner is helping. The other day Buffalo caught him up on a ladder, using a vernier caliper to measure the reveals around the window casing that Buffalo had just installed. He was checking to make sure they were each exactly 1/4 in.

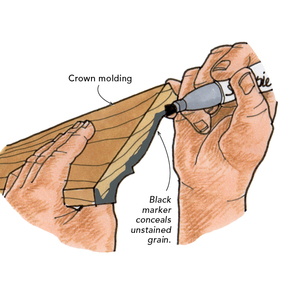

Buffalo didn’t have to move any casing, so apparently his reveals passed muster. But the homeowner also took photos of a joint in the crown molding and sent them to Buffalo’s boss. Maybe the painter could have hidden the gaps and minimized the misalignments, but we’ll never know because the homeowner insisted that it be redone. It wasn’t Buffalo’s fault—another carpenter had installed the crown—but it was Buffalo’s responsibility to fix the problem and make the homeowner happy.

The most critical aspects of a home—the structure, insulation, and mechanical systems— are subject to the scrutiny of the building department. But a building inspector is not going to make value judgments about the grout joints in your tile or the miters in your trim. Nobody’s life depends on them. Finish work just has to look good—or good enough. But what exactly is “good enough,” and who gets to decide?

Years ago, I worked with an old carpenter who used to say, “I don’t care if it’s an outhouse or a courthouse, I can find a mistake in it.” And despite wanting to add the line “We settle for perfect” to the business cards for my remodeling company, I know he was right. Perfect does not exist. Not in the real world. Every day, all day long, I make judgment calls about my own work, deciding what is and isn’t “good enough.”

Sure, I still shoot for perfect miters and perfect scribes, and everything exactly plumb, level, and square. But in the old houses I work on, the floors slope and the boards are cupped. Walls and ceilings aren’t flat. Corners are never square. And I am paid by the hour. If the initial fit of the trim is a little bit off, then making it better will cost someone money—whether it’s me, my boss, or my customer, somebody’s paying. Is it worth it? The answer depends. How bad is it? Is it interior or exterior work? Is it paint-grade or stain-grade? Is it in the back of a closet or in the front entry hall?

I will admit that, while I consider myself to be an extremely conscientious carpenter, my best work varies. So does my judgment. What time of day is it? I do my best work in the morning, when I’m rested and the day’s frustrations haven’t yet worn me down. More than once, I have begun my day by ripping out and redoing something that had seemed “good enough” at the end of the day before.

How comfortable am I? I can work under the sun in 95°F heat with 75% humidity, but I’ll do better work in the shade and even better work in the air conditioning. What kind of mood am I in? Did I just scratch off a winning lottery ticket? Or did I just have a fight with my wife?

The definition of “good enough” also varies from project to project, usually because of money. The best work takes longer and costs more. Not everyone can afford it. But it’s also true that not every homeowner cares about the details to the same degree. For example, most people do not measure the reveals around their window casing with a set of calipers. That said, there is something about the process of building and remodeling that makes people pickier than they would normally be.

“…a building inspector is not going to make value judgments about the grout joints in your tile or the miters in your trim. Nobody’s life depends on them.”

Maybe because the work costs so much money (and builders can have such sketchy reputations), homeowners want to make sure they’re getting what they paid for. But homeowners also are being asked to consider so many details—from trim tiles to drawer pulls—a process that heightens their awareness and demands that they look closely at things. It can make an otherwise normal person become strident about the difference between a piece of trim with a 1/4-in.-diameter beaded edge and one with a 3/16-in. bead. As designer Jamie Wolf puts it, “Details can take on a significance out of proportion to their place in the finished project.”

Five or six years ago, my friend Pat tackled his first really big job—a gut renovation outside of Boston. He had worked for the owners on their previous place. That project had gone smoothly, so as he put it, “I was cocky.” He assumed all would go well this time around. He was wrong.

When the owner saw the finished tile job in the walk-in shower, she was livid. The grout lines were not all perfectly straight, nor were they a consistent width. Pat said the discrepancies were 1/16 in. or less, but the owner didn’t care—she wanted a new shower. According to Pat, “It was all so emotional for her.” He thought to himself, “This is her dream house. I have to make her happy.” He also worried that without good referrals he wouldn’t be able to stay in business.

Pat ripped out the tile and had his installer redo the shower, but the result was the same. She was still unhappy. Whether to his credit or his shame, Pat ripped out the tile a second time and had a different installer tile the shower. He heard nothing for a week, then got a text from the homeowner saying that she had marked a few problem areas with tape. “When I got to the job,” Pat said, “there was blue tape everywhere.”

When a homeowner declares that something isn’t good enough, there are two possible explanations. First, you screwed up, and the work really isn’t good enough. The wrong person was assigned the task, or the right person had a bad day. It happens; you fix the problem and move on. The other explanation is trickier: Maybe the work is good enough and the client is being unreasonable. What then?

At that point, you have to ask yourself, am I fixing a legitimate problem and therefore reestablishing trust with the client? Or am I acquiescing to an unreasonable demand and ceding authority over the acceptable tolerances in my profession? You really don’t want to give up control of the job.

Some builders resolve conflicts by turning to industry standards. Various organizations offer them. If my friend Pat had known where to look in the ANSI standards, he would have found the following: “Of necessity, in any installation, some grout joints will be less and some more than the average minimum dimension to accommodate the specific tiles being installed.” He could have gone on to explain that tiles are made from clay, which naturally shrinks when fired in a kiln, and it doesn’t always shrink uniformly. That leads to minor variations in the dimensions of the tile. By varying the width of the grout joints slightly, a good tilesetter can mask the variation in the dimensions of the tile.

The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) publishes an entire manual on “good enough,” or what they refer to as “achievable minimum levels of workmanship.” It’s called the Residential Construction Performance Guidelines, and you can view a PDF online free of cost or buy a print copy for $34.

The guidelines cover everything from foundations to landscaping. In the section on interior finish, you’ll find the following: “When the contractor installs the door frame and door, the door edge will be within 3/16 inch of parallel to the door jamb.” Also this: “Individual cabinets should not have a deviation of more than 3/16 inch out of level.” And this: “…gaps between mitered edges in trim and molding will not exceed 1/8 inch.”

“…there is something about the process of building and remodeling that makes people pickier than they would normally be.”

As a veteran trim carpenter, I found the standards horrifying when I first read them. An early mentor of mine once pointed to a miter joint that was open 1⁄8 in. and said, “You could throw a cat through that gap.” These days, I draw miters together with pocket screws and beat myself up over gaps of 1/32 in. But the NAHB is not recommending 1/8-in. gaps in miter joints. They’re defining the worst possible result that would still be acceptable. Any worse and either the work gets torn out and fixed, or the lawyers get a phone call.

Of course, pointing to industry standards may not mollify an irate homeowner or keep you out of court. As my friend Pat learned, there are some people you can never make happy. But it’s important to know that industry standards exist, and their existence is a reminder that acceptable tolerances vary—from job to job, from homeowner to homeowner, and from carpenter to carpenter.

So many things affect the quality of the work I do that it would be hard to list them all. My years of experience matter, of course, but at 40-plus, it’s hard to say whether they’re a factor in favor or against. Tools make a difference. I can generally do better work in the shop than in the field because of the tools available. The difficulty of the actual task matters too. Scribing baseboard to a hardwood floor is easier than scribing a mantel shelf to a stone fireplace. I’ll likely do a better job with the former.

Ultimately, though, I am a professional, which means the variation between my best work and my worst work won’t be something most will notice. Yes, you can still catch me saying “good enough” on occasion, and it means I’m not happy with the result. I’m always aiming for perfect and usually settle for good. “Good enough” means I’m running out of time, or patience, or both, but it also means I’m pretty sure that no one else will question the result.

Of course, I’ve never worked for someone who used a feeler gauge to check the gaps around my inset cabinet doors. No wonder Buffalo still hasn’t finished that kitchen.

Kevin Ireton, editor-at-large, is a writer and remodeling contractor who divides his time between Connecticut and Arizona.

From Fine Homebuilding #303

RELATED LINKS

View Comments

Great article - very insightful. I will be looking at my work with a more critical eye, and paying more attention to my moods. Thanks!