Two Cabins Into One

How a home with roots in early American history was transformed into a modern mountain retreat.

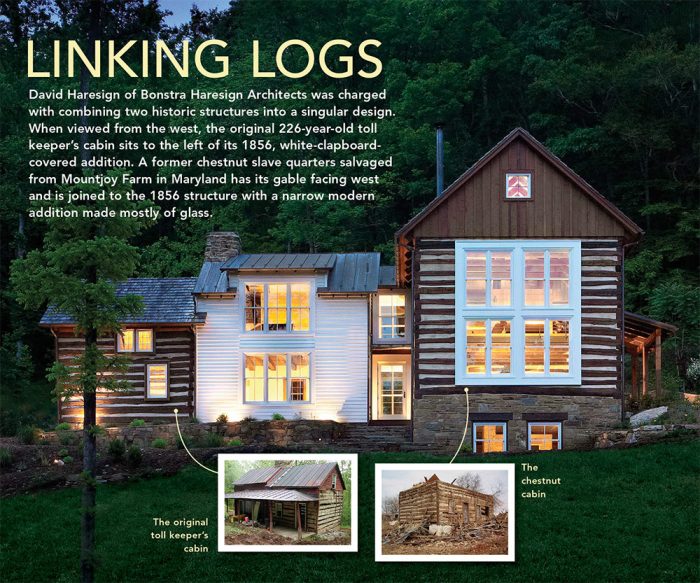

Nestled into the western slope of Jobber’s Mountain in northern Virginia sits the Hazel River Cabin, a home designed by Washington, D.C., architect David Haresign. While not everyone will find themselves in the position of redesigning a 226-year-old toll keeper’s cabin to seamlessly connect with a 165-year-old addition and a relocated 181-year-old chestnut cabin to make a new home, Haresign’s approach highlights lessons that are valuable to anyone remodeling an older home to accommodate a contemporary way of living while acknowledging and respecting its original character.

The program reveals itself

When he purchased the property, Haresign’s client, Joe, initially thought that he would have to tear down two poorly framed buildings. But after beginning demolition on the first structure, Joe discovered a 1795 toll keeper’s log cabin beneath a layer of wood clapboards. He did some research and learned about the history of the site, the cabin, and its 1856 addition. Instead of proceeding with the tear-down, Joe hired a local log-cabin restoration contractor to make a more comprehensive assessment of the building and its potential.

With its small rooms and low, 7-ft.-6-in.-tall ceilings, the cabin would be much too cramped for the home that Joe envisioned. The contractor told Joe about an additional derelict cabin, the former chestnut slave quarters from Mountjoy Farm in Howard County, Maryland, that he could procure and bring to the site. Soon after, Haresign was brought on to marry the two.

Joe wanted to use the new home as a retreat. He wanted the design to create a memorable renovation that would respect the existing character of the cabins; celebrate the beauty of the logs, wood framing, and stone fireplaces; and incorporate all of the conveniences of a modern home. The spatial program was simple: The new home would need a large modern kitchen that opened into the main living area and a dining room that could comfortably accommodate six to eight people. Joe wanted a library that could also double as an additional sleeping space. The home would need to accommodate two bedrooms, each with a private bath, with a sitting area or study nearby. These amenities, as well as an equipment room for modern mechanicals, would all need to be confined within a 2500-sq.-ft. home.

Logic in the Layout — The kitchen and main first-floor living space were positioned in the chestnut cabin, beneath a lofted master bedroom. A second bedroom, full bathroom, and mechanical room sit within the basement below the living area. The dining room is set in the 1856 addition and shares a double-sided fireplace with a den in the old 1794 toll keeper’s cabin. A lofted library and study area, which doubles as additional sleeping quarters, overlooks the space.

Contextual modernism

Some may have looked at these cabins and set out to restore them instead of transforming them into something new and different. But today, we use spaces very differently than when these cabins were originally constructed.

For restorations, renovations, additions, and adaptive-use projects, Haresign employs a simple design principle that he calls “contextual modernism.” He aims to add new elements, like modern technology and precisely manufactured components that respect and celebrate the character of the original structure, yet remain clearly contemporary.

For example, in this home, the newer elements are not hidden or blended into the old structure in any way. The modern additions, like the steel support beams, stand in stark contrast to the original structure. And while steel is a more modern material—clearly from a different period than the original log structure—it also expresses an essential, rough-hewn character that lets the two materials work remarkably well together.

While new, modern materials were utilized throughout the remodel, the team prioritized reusing the original logs whenever possible. There were several species in the original buildings, as cabin builders used whatever was available at the time. Oak, chestnut, and pine were predominant, and had survived the test of time.

The team also sought to use reclaimed materials as much as possible, either from the existing cabins, or from sources in the immediate vicinity. Eighty percent of the wood floors were reclaimed. While this home is not a technical restoration, Haresign clearly aimed to finish each cabin with a nod to its long history.

A cohesive design

All of the structures—the original log cabins, the 1856 frame addition, and he most current modern addition—have their own unique attributes. Instead of meddling with the elements in an effort to create a home with a universal feel from space-to-space, the design and build team embraced and showcased the contrasting elements. The differences in these spaces and materials, which can be severe in certain instances, helped create a clear composition. Walking through the home, an observer can easily understand the age of each space and its relationship to the present and to the past.

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Photos by Anice Hoachlander, except where noted.

RELATED LINKS: