Dropped First-Floor Framing

Are there any ways to build the first floor with a reduced number of steps? One of our building experts explains how to reduce entry steps.

I’m designing a house, and I want as few steps into it as possible at the entry. According to the local inspector, we have to leave 8 in. of the foundation showing above the surrounding soil. Add that to the height of the mudsill, plus the 14-in. engineered joists, and the top of the finished floor will be four stair risers above grade. I’d prefer no step, or just one. Are there any ways to build the first floor with a reduced number of steps?

—Steward Kim, via email

Editorial advisor Mike Guertin replies: You may be wondering where the code-required 8-in. height between grade and top of foundation comes from. The International Residential Code (IRC) has two sections that guide how much the foundation must extend above the surrounding grade. Section R404.1.6 requires a minimum of 6 in. between finished grade and the top of the foundation unless there will be masonry-veneer cladding. In that case, the minimum requirement is only 4 in.

I think your inspector is citing a different subsection that describes where naturally durable wood or preservative-treated wood is required. Section R317.1 requires pressure-treated wood for “framing members that rest directly on concrete or masonry exterior foundation walls and are less than 8 inches from the exposed ground.” That implies untreated framing lumber can be used if the top of the foundation is 8 in. or more above grade.

Presuming that you’re not cladding the exterior with masonry veneer, the minimum height above grade to the top of the foundation is 6 in. There’s no requirement that you stack the floor framing on top of the foundation. Instead, you can install the floor joists between the foundation walls so they’re flush with or slightly higher than the top of the foundation. The trick is supporting the joists. I’ve used three different methods; one will probably work for you.

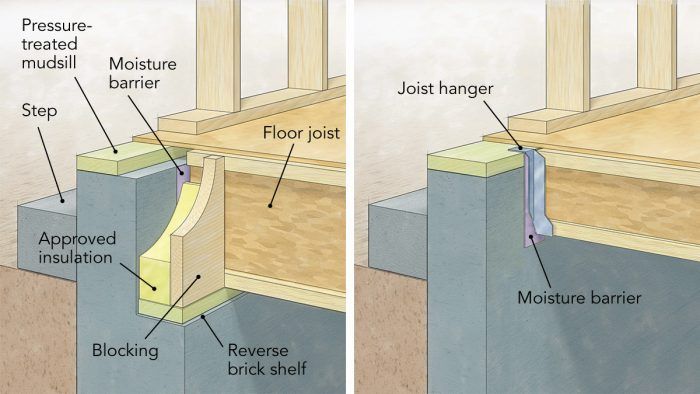

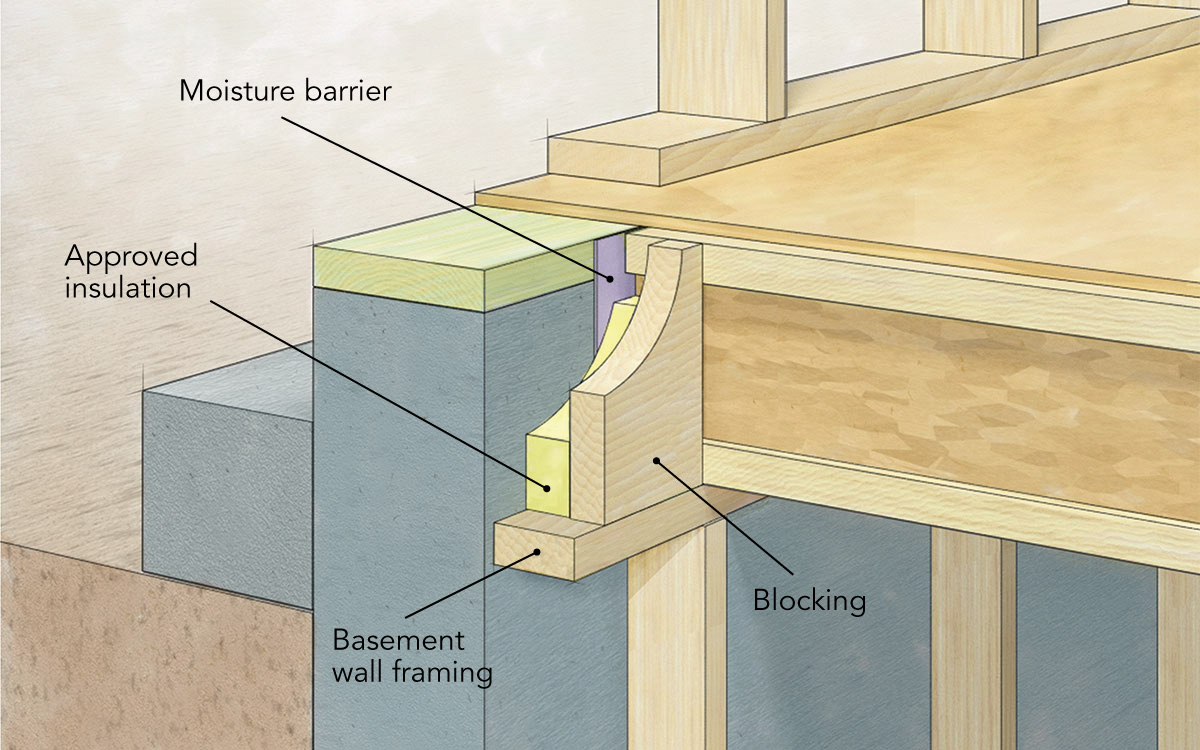

The first option is to create a reverse brick shelf. Ask the foundation installer to form an inward-facing brick shelf about 6 in. deep and 14 in. tall with anchor bolts on the shelf. If you’re using concrete masonry units for the foundation, the mason can build up the wall with 10-in. or 12-in. blocks and then use 6-in. blocks for the top two courses to create the same shelf effect. The joists can rest on the shelf and will be roughly flush with the top of the foundation, leaving a single step into the house. Frame the floor by installing pressure-treated 2x mudsills on both the top of the foundation and the shelf. The top of the joists will flush out with the top of the upper mudsill, and when the subfloor sheathing is installed, it will bridge across the gap and tie the floor together from outside of the foundation along one side to the opposite. You may need to install solid block between the I-joists if required by the manufacturer’s instructions.

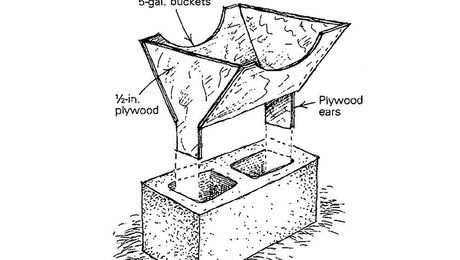

Another way to go about this foundation-level floor is to hang the joists. Instead of forming a reverse brick shelf, form it with a regular flush inside face. Install a mudsill on top of the foundation as you ordinarily would, but make it the full width of the concrete. Use top-flange-style joist hangers to support the joists hung from the mudsill. The floor sheathing can bridge over the hangers and onto the mudsill perimeter.

The last method I’ve used to support the joists on the inside is to form a regular foundation and place the slab inside. Install a mudsill on the foundation’s outer face. Then frame up walls on the inside face of the foundation 14 in. shorter than the top of the mudsill for the first-floor joists to rest on. The floor sheathing will plane across the mudsill and the joists.

All three approaches require a capillary break between the untreated joists and the masonry surface of the foundation wall. To accomplish this, cut the joists to allow for a 1/2-in. gap between the two, or install a moisture barrier such as butyl or bituminous flashing tape or strips of thick polyethylene.

Because all these approaches add a 1-1/2-in.- thick mudsill on top of the 6-in. exposed foundation wall, the distance from the grade to the top of the door threshold will be around 8 in. to 9 in. You can install one step with two short risers to enter the house, or you can check with the building inspector to see if this idea may be acceptable: Place concrete or pavers for a walkway that is higher than the surrounding grade by a few inches and about 7 in. below the top of the entry-door threshold. This will leave you with just one riser to enter the house.

From Fine Homebuilding #305

RELATED LINKS

View Comments

I too wanted as few exterior steps as possible into a house for which I just finished the construction drawings. I employed the first of the three solutions proposed here by Mike Guertin - the one using the inward-facing shelf. Last week the contractor looked at the drawings for the first time and upon seeing this detail asked, “How am I supposed to get my electric from the panel in the basement up to the first floor?” I did not have an answer for him, but I hope someone in the FHB community does.

To help with visualizing things I’ve attached a detail of the more-often-used arrangement of joists on top of the mud sill, rather than below the mud sill as illustrated in this article. (Click on icon below.) One can see how in this standard detail, wire/cable easily passes through the basement perimeter joist space and up into first floor perimeter walls.

My ramblings: If there were enough interior partitions on the first floor, perhaps one could run wiring across the basement ceiling/ joists and up through the interior partitions rather than up perimeter walls?? If this is indeed a viable solution though, an added issue with my particular house as to why this solution wouldn’t work is that the first floor is mostly open plan with few interior partitions and the second floor is a more traditional layout with many interior partitions for bedrooms, bathrooms and closets. There aren’t enough interior partitions on the first floor through which to run wiring up to the second floor. Help!!

I'm wrestling with the same issue in my design. I started out with the idea of a lower floor stud wall supporting the main floor joists but had some concerns with building that stud wall level on top but sitting on a slab that will no doubt have some variation. My other concern was the same as yours, difficulty with electrical and with some plumbing to outside faucets.

For those two reasons I'm now revising my design to the ledge approach. My main floor will use double exterior walls and the ledge method now gives access for electrical as the inner wall will be above the space created by the ledge.

That doesn't work in your situation unless you have some unusually thick exterior walls. Here are some possible ideas:

1) Go up through partition walls wherever practical.

2)Consider building out one or more wiring chases where possible. If your HVAC is coming from the basement, how does it get to the second floor? If you need a chase for HVAC maybe you can run electrical there.

3)Can you accommodate some short pony walls in selected locations - essentially making a double wall that would allow you to feed electrical into the short wall and then into the outer wall. The pony wall(s) could be built to make a shelf, bookcase, or other built-in giving it some purpose.

None of these are great ideas but that's all I can come up with at this point.

utilities (plumbing and electric) can be run vertically from the basement into any interior wall that runs perpendicular to the exterior wall and then horizontally through the interior wall into the exterior wall.

How might option two work with an ICF foundation with 2-5/8" foam on the interior?

With an ICF foundation you can use the Simpson Strong Tie ICF ledger brackets. They embed in the foam before the concrete is placed in the forms. A ledger is then fastened along the interior face of the wall to hang the joists from rather than resting the joists on top of the foundation.