Keeping Cathedral-Ceiling Walls From Bowing

Compensate for sagging in the roof by bowing in the sidewalls before securing the rafters.

I built an open plan second floor space with a cathedral ceiling, and even though I used lots of braces as I was framing it and fastened the collar ties really well, the eaves still bowed out a little bit when it was done. How could this have been prevented?

—Owen Planer, via email

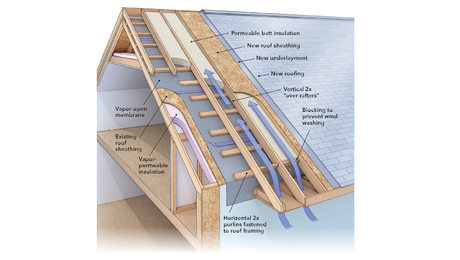

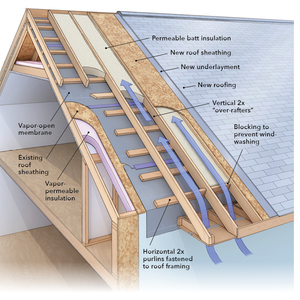

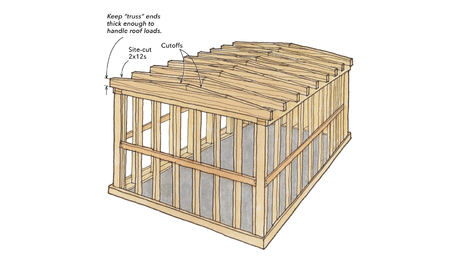

John Spier, a builder from Block Island, R.I., replies: The strength and stability of a gable roof comes from triangulation. As gravity pushes down on the rafters, the lower ends want to push outward against the walls, and this force is resisted by the ceiling joists or collar ties. If the building has a full attic and the ceiling joists are fastened to the top plates, the walls can’t move. But many roofs are designed with cathedral ceilings, where the ceiling joists are omitted, or are replaced with collar ties attached to the rafters higher up. Interestingly, the shallower the roof pitch, the more outward pressure is generated. This pressure can be resisted in two ways; with a structural ridge large enough to carry all the loads on the upper half of the roof (the side walls carry the lower half), or more commonly, with members such as rafter ties and ceiling joists that keep the rafters from pushing the walls out. Many designs use a combination of these methods.

John Spier, a builder from Block Island, R.I., replies: The strength and stability of a gable roof comes from triangulation. As gravity pushes down on the rafters, the lower ends want to push outward against the walls, and this force is resisted by the ceiling joists or collar ties. If the building has a full attic and the ceiling joists are fastened to the top plates, the walls can’t move. But many roofs are designed with cathedral ceilings, where the ceiling joists are omitted, or are replaced with collar ties attached to the rafters higher up. Interestingly, the shallower the roof pitch, the more outward pressure is generated. This pressure can be resisted in two ways; with a structural ridge large enough to carry all the loads on the upper half of the roof (the side walls carry the lower half), or more commonly, with members such as rafter ties and ceiling joists that keep the rafters from pushing the walls out. Many designs use a combination of these methods.

All frames settle and move as the loads of building finishes are added to them. There are two primary ways that these loads force the walls outward. The first is the crowns in the rafters; most lumber has slight bends or crowns, and we install rafters and joists with the crowns up, so that as they load, they straighten. Of course, as they do that, they get slightly longer, and because the tops are pushing against each other, the bottoms have to move out. Secondly, every joint and fastening in a frame has a little bit of give in it, and most lumber is used green, or slightly wet. As the structure settles, dries, shrinks, and loads, there will always be some movement.

The trick is to anticipate these forces and their effects, and to plan for them. When you’ve built your walls and they’re ready for the roof, set up stringlines and brace the sidewalls where the rafters will rest. But instead of bracing them perfectly straight, bow them in slightly. Experience will tell you how much, depending on the roof pitch, span, lumber quality, etc., but 1/4 in. in 30 ft. would be typical. Once the braces are removed and the building settles into stability, everything should straighten. If you run your rafter tails long, if possible, wait until the assembly settles a bit before you snap a line and trim them to size.

Two last things to keep in mind: If you end up with a slight crown in the ridge and the eaves bowed slightly inwards, only a very practiced eye will ever see it, but a sagging ridge and convex eave will be obvious to anyone. And lastly, gravity never rests; even the strongest building will move after a few centuries. You might as well get a head start on it!

Photos by Patrick McCombe

RELATED STORIES

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Flashing Boot

Roof Jacks

Roofing Gun