Planning an All-Electric Home

Going all-electric can improve a home's safety, comfort, and energy costs, but making the switch may seem daunting. Here's how to start the process.

Weaning households off natural gas, heating oil, and other fossil fuels would mean significant reductions in carbon emissions, but there’s a catch. From furnaces to water heaters to kitchen ranges, fuel-burning appliances are deeply entrenched in U.S. homes. Even homeowners who’d like to go all-electric may feel overwhelmed by the complexity and expense of the conversion.

For people who find themselves in this boat, a California energy consulting firm has some reassuring news: The process can be simple, relatively inexpensive, and require no building modifications, not even an upgrade in the electrical service panel to anything over 100 amps.

“You are not alone in this project of electrifying your home,” says the introduction to A Pocket Guide to All-Electric Retrofits of Single-Family Homes. “And it can be cheap and easy.”

The guide was produced by Redwood Energy, zero-net energy specialists in multifamily housing, for a non-profit community organization called Menlo Spark. It’s one of several publications Redwood has produced that are aimed at accelerating a trend toward the use of electric devices. “The global scientific community says that fossil fuels burned in our buildings are causing 28% of climate change,” it adds, “with natural gas leaks upstream of our appliances responsible for another 25% of global climate change.”

In a telephone call, Redwood’s Managing Principal Sean Armstrong said the new pocket guide is the latest in a series on electrification that also covers commercial buildings, new single-family homes, and multifamily projects. After publishing the single-family guide at the beginning of 2020, the company turned its attention to the retrofit publication and has been working on it for the last year. An early draft went out for peer review and the company posted a final version at its website within the last couple of weeks.

The earlier booklet on commercial construction was intended to help big companies electrify new construction. That turned out to be “modestly successful,” Armstrong said, with Adobe and LinkedIn committing to a couple of all-electric construction projects.

“The booklet did something,” he said. “It changed people’s thinking. It got in front of people and helped them see what options were there.”

The benefits of going all-electric

Cutting carbon emissions from buildings is an important part of government efforts to slow global climate change. Some green builders also are getting pickier about the building materials they use in an effort to cut the embodied carbon in new construction.

Redwood Energy cites a variety of other benefits to electrification:

- Better indoor air quality and better health. Children in homes with gas stoves are 42% more likely to develop asthma, and home chefs using gas stoves have twice the risk of developing lung cancer and heart disease.

- Enhanced safety. Electric cooktops, water heaters, and other appliances are less likely to cause fires and explosions than devices powered by gas.

- Lower costs. Households with all-electric appliances can save as much as $800 a year on utility bills. The installation of solar arrays can mean even greater savings.

- Greater comfort. Heat pumps are quieter and produce heat more consistently than gas-fired furnaces that cycle on and off; electric stoves produce half as much waste heat as gas-fired ranges.

Potential savings from going all-electric were outlined in another report, this one from the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) that was released late last year. It predicted savings in an all-electric new house in seven U.S. cities compared with a mixed-fuel home that used gas for cooking, space heating, and water heating. Savings ranged from $1600 in net present costs and reduced carbon emissions of 51 tons over 15 years in Boston, to a high of $6800 in savings and 46 fewer tons of C02 in New York City. Other cities covered in the RMI survey included Austin, Columbus, Denver, Minneapolis, and Seattle.

RMI has published a number of articles on electrification, including this one late last year summing up progress toward that goal in a number of states.

Despite the new attention it’s getting, electrification really isn’t new, Armstrong said. It can be traced to the Rural Electrification Administration created in 1935 by President Franklin Roosevelt; later, it found a big advocate in President Ronald Reagan.

“It’s been a 70-year-long movement,” Armstrong said, and should not be viewed as a partisan issue.

Two paths to all-electric

The Redwood Energy guide sees two paths toward electrification: an appliance-by-appliance conversion, which it calls “box swapping,” and deep retrofits that may include improvements to the building enclosure. “Either of these types of retrofits can be done quickly, or phased in over the course of years,” the authors say, “depending on the owner’s needs.”

Costs will vary widely. In an incremental conversion, where a gas-burning appliance is replaced with an electric model, there may be no cost difference between the two options other than running electricity to the new appliance. When all appliances are replaced at once, costs may range from $3000 on the low end—an option that includes a two-burner countertop induction range rather than a full-size stove, for example—to $20,000 or more. “Every house is different,” the authors note, “and people have different tastes and desires.”

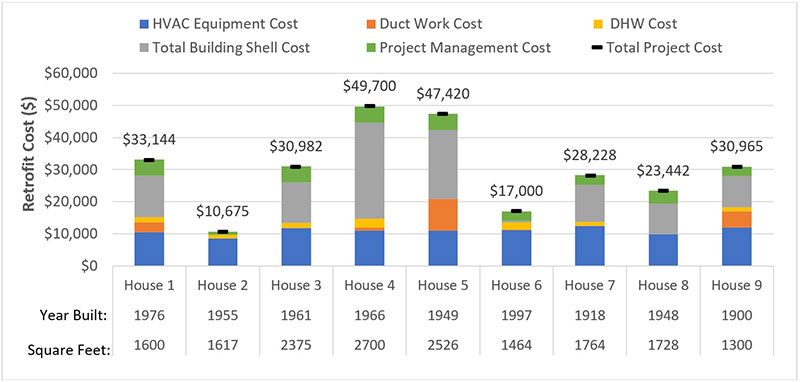

In case studies from Energy Smart Ohio, total retrofit costs were as high as $49,700 in a 2700-square-foot home built in 1966, a project that included roughly $20,000 in upgrades to the building enclosure. At the low end was $10,675 for a 1617-square-foot house where space and water heating equipment was replaced but no improvements were made to the building enclosure.

The authors of the report looked at the box-swapping option a room at a time, presenting the cost of converting from a gas appliance to one of several types of electrically powered appliance. In this case, it may be possible to avoid retrofit costs by choosing an appliance of the same size, and avoid wiring upgrade costs by using energy efficient equipment or by using devices called power-sharing plugs.

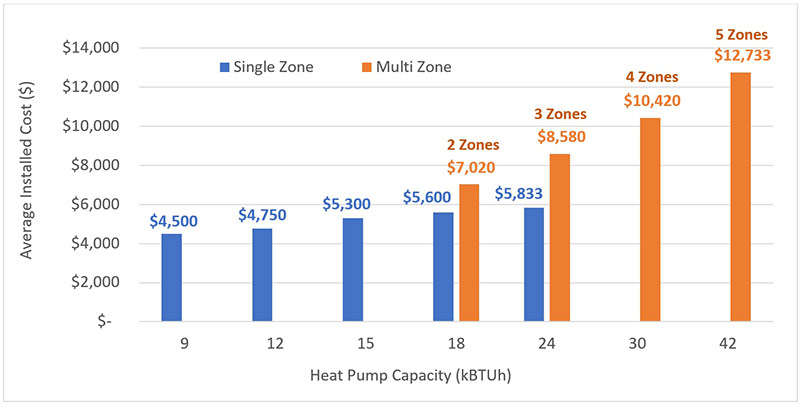

The cost of a conversion, of course, depends on the appliance. To replace a gas range with an electric model, a consumer could spend less than $1000 for a 24-inch model to an average of more than $1500 for a 36-inch-wide model (not including the cost of running a new electrical circuit). Converting to a heat-pump water heater is more expensive (costs averaged around $4000 in Sacramento, California, for a 50-gallon model, including labor and materials) but the big nut to crack is probably space heating. Redwood Energy said that it developed its estimates after contractors from different parts of the country agreed to share their bids. A house typically required between 1 and 3 tons of capacity (12,000 to 36,000 Btu/hour) for heat, with per-ton costs ranging from a low of about $3100 to a high of $6000 in the states that were sampled.

Variables would, of course, include insulation, windows, measured heat loads, and the condition of any ductwork that was used in a retrofit. End costs to consumers also would hinge on what rebates a particular state offered for a targeted appliance. One place to check for those is at the Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency, which is maintained by the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center.

Avoiding expensive electrical upgrades

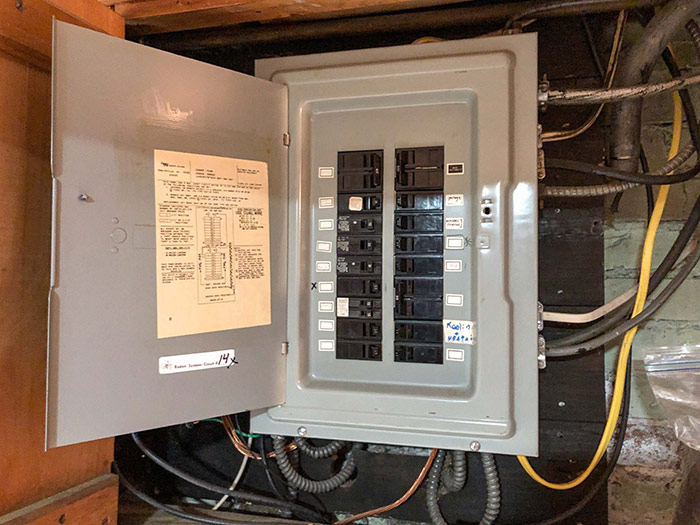

Many new homes get 200-amp service panels, providing plenty of electricity for appliances (with the exception of outliers like electric tankless water heaters). But older houses are often stuck with 100-amp panels, sometimes less, and wiring that has been modified by well-meaning amateurs to the point where some circuits are overloaded, some are under-used, and the system is generally something of a mystery.

Homeowners thinking about upgrades to appliances that draw a lot of power might have second thoughts if the work would necessarily include major rewiring and an upgrade to a 200-amp service entrance. Running 240-volt cables to stoves, water heaters, clothes dryers, and space heating equipment costs as much as $600 per circuit and averages $300, the guide notes, while a new service panel averages $1475.

That said, there are ways of using the power that’s available without a panel upgrade while still following the National Electrical Code (NEC), as the authors say: “We call this process of avoiding power upgrades a ‘Watt Diet,’ which involves power-efficient appliances and sometimes power balancing plugs.”

In fact, the report says a 100-amp panel has enough electricity to completely electrify a 3000-sq.-ft. home. Most houses need no more than the NEC minimum of a three-wire, 100-amp service entrance. To bolster its case, the guide describes a set of appliances that would fit into an all-electric, 100-amp home, including a 21-amp heat-pump water heater and a 3-ton heat pump for heating and cooling.

Armstrong said that in figuring out how to make seemingly under-sized service panels take care of an all-electric house, it’s important to understand the difference between actual electrical draw and the capacity of the circuit breaker. For example, a water heater may require a 30-amp, 240-volt breaker, but that doesn’t mean it’s actually using that much electricity.

“The breaker is not the issue,” he said, “it’s really the electrical demand.”

The report’s recommendations to make all of this possible include:

- Use heat pumps rather than electric resistance heating. Heat pumps are between 3 and 5 times as efficient.

- Get a condensing, combined washer/dryer, which can be plugged into any 120-volt outlet and does not have to be vented to the outside.

- Use a combined range and oven rather than separate units, and put the microwave oven on the counter rather than attaching it to the wall where it would require a dedicated circuit.

- Insulate and air-seal the house to reduce heating loads.

- Use circuit-sharing plugs, which allow one 240-volt outlet to power both an electric vehicle and an electric appliance. Once such device is the NeoCharge.

The same could be accomplished with a 3000-square-foot house, the report adds, when automatic circuit sharing devices are added for an electric dryer and heat-pump water heater, and for an electric stove and electric vehicle.

Elsewhere at the Redwood Energy site is a downloadable app called the Watt Diet Calculator that can be used to estimate how much electricity will be used and whether the electrical panel will have to be upgraded.

Devices that don’t need 240-volt circuits

Switching to electrically powered water heating or space heating and cooling usually means running new 240-volt lines, but that’s not always necessary. While the pocket guide lists a number of heat-pump water heaters that require 240-volt circuits, it also includes two that run on 120-volt current, meaning they could be plugged into any households circuit.

The pocket guide lists two—the GE GeoSpring, available in 40- and 50-gal. sizes, and the Rheem Prestige Hybrid, a 40-gal. model. Armstrong said in a telephone interview that A.O. Smith also would begin offering a similar model this year.

(Rheem, however, said in an email that it does not currently offer a 120v model and declined to say if or when it would in the future. GE no longer produces GeoSpring heat-pump water heaters. Bradford White, which took over the GeoSpring line in 2017 and now sells them under the AeroTherm label, said there is no pending release of a 120v model. A.O Smith didn’t respond to requests for information.)

Four manufacturers offer portable heat pumps running on 120-volt circuits that can plug into any outlet in the house. Ducts fit into a window opening. They include models from Edge Star, Black + Decker, Whynter, and Haier. The Black+Decker draws a maximum of 9 amps and has a heating capacity of as much as 11,000 Btu/hour.

Don’t feel like investing $1000-plus in a new induction range? What about a single-burner induction burner you can plug into a 120-volt circuit? The guide lists more than a dozen models, both countertop and drop-in, available for as little as $40. Two-burner, 120-volt models are available for $150.

These products are part of an extensive catalog of devices that cover everything from heating and cooling to cooking, water heating, whole-house ventilation, countertop ovens, kitchen hoods, and even slow cookers. There’s even a section on electrically powered landscaping tools like chainsaws, lawnmowers, and hedge trimmers, plus a listing of three battery-driven snowmobiles.

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. Scott Gibson is a contributing writer at Green Building Advisor and Fine Homebuilding magazine. This post was updated on March 25 to include new information about heat-pump water heaters.